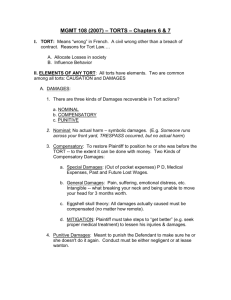

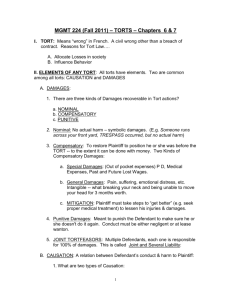

Law-140-Torts-Bobinski-by-Bernstein-term-2-2007

advertisement