Governance and NTFP

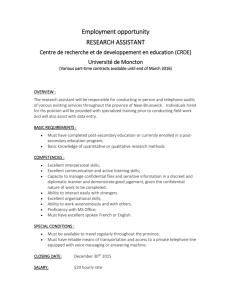

advertisement