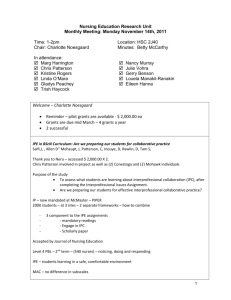

Psychosocial Oncology Objectives

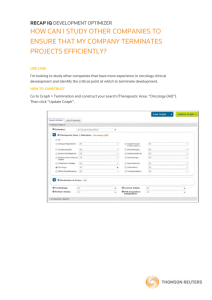

advertisement