antonín dvorák - The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

advertisement

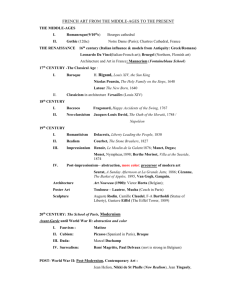

Notes on the Program by DR. RICHARD E. RODDA Nocturnes for Two Pianos Claude Debussy Born August 22, 1862 in St. Germain-en-Laye, near Paris. Died March 25, 1918 in Paris. Arranged by Maurice Ravel Composed for orchestra in 1897-99; Sirènes arranged in 1901, Nuages and Fêtes arranged in 1909. Orchestral version premiered on October 27, 1901 in Paris, conducted by Camille Chevillard; arrangement of Sirènes premiered on April 20, 1903 in Paris; complete arrangement premiered on April 24, 1911 in Paris by Ravel and Louis Aubert. Duration: 21 minutes Maurice Ravel was born in 1875 in Ciboure, south of the coastal city of Biarritz, and three months later moved with his family to Paris. He began piano lessons when he was seven, started studying music theory five years later, and in 1891 entered the Paris Conservatoire. Ravel immersed himself in the musical life of the capital during those years, and he was especially impressed with performances of Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun), La Damoiselle élue (The Blessed Damozel), and Proses lyriques by Claude Debussy. Thirteen years Ravel’s senior and a recent graduate of the Conservatoire, Debussy was quickly becoming one of France’s most prominent (and most controversial) composers. Debussy learned about Ravel from their mutual friend pianist Ricardo Viñes, who in March 1898 invited Debussy to the premiere of the Sites auriculaires (Scenes for the Ear), Ravel’s public debut as a composer. Viñes admitted that he and his keyboard partner for the performance, Marthe Dron, “made a mess of it,” but Debussy was intrigued enough with the piece to ask Ravel for a copy of the score. Though the fastidious Ravel and the profligate Debussy could probably never have been intimate friends, they shared interests in contemporary French poetry, art, literature, and music, frequented some of the same salons, had many colleagues in common, and spoke glowingly of each other’s talents: “the most phenomenal genius in the history of French music,” said Ravel of Debussy; “the most refined ear there has ever been,” responded Debussy. Debussy and Ravel also found a personal bond in Raoul Bardac, an aspiring composer who was a fellow student of Ravel at the Conservatoire and a private pupil of Debussy. (In 1904, Debussy abandoned his first wife, Lilly, for Raoul’s mother, Emma, a gifted amateur singer, wife of a noted financier, and former mistress of Gabriel Fauré, Ravel’s teacher. Their marriage four years later, following a suicide attempt by Lilly, created a good deal of animosity among the Parisian public toward Debussy.) In April 1901, Ravel and Bardac settled on a plan to make two-piano versions of Debussy’s three Nocturnes for Orchestra of 1897-99, the first two of which, Nuages and Fêtes, had been premiered at a Lamoureux Concert the preceding December. (A women’s chorus could not be assembled in time to perform in the closing Sirènes. The movement was first heard on October 27, 1901 as part of the premiere of the complete Nocturnes.) “Having shown some ability for this work,” Ravel wrote to the composer Florent Schmitt, “I was assigned the task of transcribing Sirènes all alone. It is perhaps the most perfectly beautiful of the Nocturnes and certainly the most perilous to transcribe.” The arrangement of Sirènes was played in Paris on April 20, 1903, but Ravel did not get around to transcribing Nuages and Fêtes until 1909; when the scores were published later that year they did not mention Bardac. Ravel played all three Nocturnes on April 24, 1911 at the Salle Gaveau with Louis Aubert, pianist, composer, and dedicatee that year of Ravel’s Valses nobles et sentimentales. The personal relationship between musical Impressionism’s two seminal figures started its decline in 1904 with the premiere of Ravel’s String Quartet, a genre Debussy had broached a decade before. Though Debussy praised the piece (“in the name of the gods of music, and in mine,” he wrote to Ravel, “do not touch a single note of what you have written”), the rancorous public and critical debate over the relative merits of the two works pitted the friends against each other in a confrontation that neither could win. Their differing personalities and disparate musical styles — sonority-driven and mistily evocative for Debussy, precise and classically based for Ravel — were already driving them apart by that time, and they were estranged by 1908. “It’s probably better for us, after all, to be on frigid terms for illogical reasons,” Ravel later rationalized. Debussy himself caught the delicate blending of reality and imagination in his poetic description of the Nocturnes: “The title Nocturnes is intended to have here a more general and, more particularly, a more decorative meaning. It is not meant to designate the usual form of a nocturne, but rather all the impressions and the special effects of light that the word suggests. “Nuages (Clouds): the unchanging aspect of the sky and the slow and solemn march of clouds fading away in gray tones slightly tinged with white. “Fêtes (Festivals): vibrating, dancing rhythm, with sudden flashes of light. There is also the episode of a procession (a dazzling, fantastic vision) passing through the festive scene and becoming blended with it; but the background remains persistently the same: the festival with its blending of music and luminous dust participating in the universal rhythm of things. “Sirènes (Sirens): the sea and its endless rhythms; then amid the billows silvered by the moon, the mysterious song of the Sirens is heard; it laughs and passes.” Petite Suite for Piano, Four Hands Claude Debussy Composed in 1886-89. Duration: 13 minutes During the early years of his life, before he fell under the influence of Eric Satie and the Symbolist poets, Debussy turned to the refined style of Couperin, Rameau, and the French Baroque composers for inspiration in his instrumental music. Several works of that time are modeled on the Baroque dance suite, including his most popular piece, Clair de Lune, originally conceived as a simple slow movement for the Suite Bergamasque of 1889, the year in which he completed the Petite Suite. Like the Suite Bergamasque, the Petite Suite comprises brief dance movements that reflect the concise form and clear melody of their models. Each of the four movements bears a title reflecting its general character. En bâteau (In a Boat) is a lullaby-barcarolle that uses whole-tone scales in its central section. Cortège displays none of the funereal solemnity usually associated with pieces of that name, but rather calls to mind a pleasant stroll along the sun-dappled bank of a bubbling stream. Since Debussy associated the paintings of Watteau with Rameau’s music, this Cortège may have been meant to summon the elegant sensuality of such a canvas as The Embarkation to Cythera. The following Menuet is a wistful evocation of the most durable of all Baroque dances. The lively Ballet that closes the Petite Suite is not music for choreography, but rather recalls the Italian balletti of the 16th century, the dance-like vocal pieces for home entertainment that were imported into England as balletts (the “tt” is pronounced) and distinguished by their characteristic “fa-la-la” refrains. Jeux, poème dansé for Two Pianos Claude Debussy Arranged by Jean-Efflam Bavouzet Composed in 1912-13. Premiered on May 15, 1913 in Paris, conducted by Pierre Monteux. Duration: 16 minutes In May of 1912 Sergei Diaghilev and his Ballets Russes staged a production of Debussy’s 1894 Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun in which Vaslav Nijinsky danced the title role and provided choreography sufficiently lubricious to cause a scandal. Following the publicity-stimulating furor over Faun, Nijinsky devised a new scenario. Diaghilev saw it as an opportunity to move the Ballets Russes away from the nymphs and fantasies of his earlier productions and toward a bold modernity in subject and treatment. Nijinsky’s scenario used the modish game of tennis (which, incidentally, Nijinsky did not try playing until 1916 in New York) as the catalyst for a sensual episode of flirtation: The scene is a garden at dusk; a tennis ball has been lost; a young man and two girls are searching for it. The artificial light of the large electric lamps shedding fantastic rays about them suggests the idea of childish games: they play hide and seek, they try to catch one another, they quarrel, they sulk without cause. The night is warm, the sky is bathed in pale light; they embrace. But the spell is broken by another tennis ball thrown in mischievously by an unknown hand. Surprised and alarmed, the young man and the girls disappear into the nocturnal depths of the garden. Diaghilev and Nijinsky approached Debussy about composing the music for this thinly veiled erotic gambol, titled Jeux (Games). “No,” he told them. “It’s idiotic and unmusical! I would not dream of writing the score.” Changes were made to overcome Debussy’s objections to the scenario, pleas were issued, and the fee was doubled; Debussy accepted the commission. The score was sketched in the fall of 1912, the orchestration was done quickly between March 28 and April 24, 1913, and Jeux was premiered at the Théâtre des Champs Élysées on May 15. The two-piano transcription of Jeux is by the internationally acclaimed French pianist Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, who performs the top part in this performance. He writes: “Debussy, writing to Jacques Durand on September 13, 1913, referred to a transcription of Jeux for two pianos that he was completing. Unfortunately, the score has never been found. The idea of actually doing this was given to me by Klaus Lauer, director of the Römerbad Musiktage in Germany, and when the work was premiered at Badenweiler in 1998, Jeux, poème dansé for Two Pianos Zoltán Kocsis, himself an experienced transcriber, proved to be a devoted and inspirational partner. Knowing how attached Pierre Boulez is to this composition, I would like to express my gratitude to him; after receiving the score, he confirmed the interest there would be in a ‘black and white’ version of the work, bringing it quite amazingly close to other works written for piano (pianos) at the same time. I trust that the transcription will give everyone who plays it and everyone who hears it as much pleasure as I have had writing it.” Jeux d’enfants for Piano, Four Hands Georges Bizet Born October 25, 1838 in Paris. Died June 3, 1875 in Bougival, near Paris. Composed in 1871. Duration: 20 minutes Jeux d’enfants (Children’s Games), one of the most charming and effervescent creations in the entire realm of music, was a product of the most difficult time of Georges Bizet’s life. On June 3, 1869 in Paris, Bizet married Geneviève Halévy, daughter of the famed composer (most notably of La Juive, one of Caruso’s favorite operas) and his teacher, Jacques Halévy. Geneviève was, alas, too much the child of her mother, who was subject to frequent psychotic attacks intense enough to require her confinement. Geneviève likewise suffered from emotional instability throughout her life, and she was especially unnerved by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in July 1870 and by the four-month siege of Paris that began in September. By January 1871, Bismarck’s troops had gobbled up sufficient political booty in the form of Alsace and Lorraine, and an armistice was proclaimed. Georges took his wife to visit Mme. Halévy in Bordeaux, but within two days her mother’s company had reduced Geneviève to such a state of nervous prostration that she begged to be taken back to Paris. The Prussians entered Paris again in March, however, and the Bizets were forced to flee to Le Vésinet outside the city. The invaders withdrew two days later, leaving the city ripe for civil strife, and an extreme leftist group, opposed to the humiliating treaty terms proposed by Germany to the Thiers government based at Versailles, determined to establish a Commune. The Communards erected barricades, shot hostages (including the Archbishop of Paris), burned the Tuileries and the city hall, and created havoc among the citizens. The Bizets listened to the cannonade in the distance for weeks. On May 28, 1871, the Versaillais marched on the city (while the Prussians stood by as neutrals), crushed the rebellion, and in retaliation executed some 17,000 persons, including women and children. The Bizets returned to their flat, fortunately undamaged, in early June. Out of the turbulent situation in 1871, however, came one of Bizet’s most delightful works, a suite of miniatures for piano, four hands titled Jeux d’enfants. Little is known about the inspiration or creation of the work. The published score bears a dedication to “Mesdemoiselles Marguerite de Beaulieu et Fanny Gouin,” daughters of Geneviève’s cousin (with whom she lived before marrying Georges) and a close friend of the family, and the music may have been created for their entertainment or participation. “Each movement of Jeux d’enfants is vividly illustrative of a facet of childhood,” wrote Winton Dean in his study of Bizet, “but there is not a trace of triviality, self-consciousness or false sentiment.” L’Escarpolette (The Swing) is depicted by a halcyon melody draped across contented back-and-forth arpeggios. La Toupie (The Top) spins energetically, wobbles to a stop, and then does it again. La Poupée (The Doll) is a gently rocking lullaby. Les Chevaux de bois (Merry-Go-Round) is evoked by galloping equine rhythms and a few giddy harmonic surprises. Tiny, airborne phrases suggest the short flights of Le Volant (The Shuttlecock) in a game of badminton. Bizet originally composed the march Trompette et Tambour (Trumpet and Drum) for his 1865 opera Ivan the Terrible. The evanescent gestures of Les Bulles de Savon (Soap Bubbles) conjure up the glint, wayward motion, and short life of its subject. The bustling rhythms and bursts of activity of Les Quatre Coins (The Four Corners) suggest the playing field of a children’s game. The hesitant figures of Colin-Maillard (Blind Man’s Buff) recall the movements of a blindfolded child searching for his playmates. Saute-Mouton (Leapfrog) jumps and scampers and leaves itself breathless at the end. A sweetly sentimental Duo evokes two youngsters playing house in Petit mari, petite femme (Little Husband, Little Wife). Jeux d’enfants closes with a sparkling Galop titled Le Bal (The Ball). An American in Paris for Two Pianos George Gershwin Born September 26, 1898 in Brooklyn, New York. Died July 11, 1937 in Hollywood, California. Composed in 1928. Duration: 18 minutes In 1928, George Gershwin was not only the toast of Broadway, but of all America, Britain, and many spots in Europe as well: he had produced a string of successful shows (Rosalie and Funny Face were both running on Broadway that spring), composed two of the most popular concert pieces in recent memory (Rhapsody in Blue and Concerto in F), and was leading a life that would have made the most glamorous socialite jealous. The pace-setting Rhapsody in Blue of 1924 had shown a way to bridge the worlds of jazz and serious music, a direction Gershwin followed further in the exuberant yet haunting Concerto in F the following year. He was eager to move further into the concert world, and during a side trip in March 1926 to Paris from London, where he was preparing the English premiere of Lady Be Good, he hit upon an idea, a “walking theme” he called it, that seemed to capture the impression of an American visitor to the city “as he strolls about, listens to the various street noises, and absorbs the French atmosphere.” He worried that “this melody is so complete in itself, I don’t know where to go next,” but the purchase of four Parisian taxi horns on the Avenue de la Grande Armée inspired a second theme for the piece. Later that year, a commission for a new orchestral composition from Walter Damrosch, music director of the New York Symphony and conductor of the sensational premiere of the Concerto in F, caused Gershwin to gather up his Parisian sketches, and by January 1928, he was at work on the score: An American in Paris. The two-piano draft was finished by August 1st, and the orchestration completed only a month before the premiere, on December 13, 1928. An American in Paris, though met with a mixed critical reception, proved a great success with the public, and it quickly became clear that Gershwin had scored yet another hit. For An American in Paris, as for his other orchestral compositions, Gershwin created a fully finished score for two pianos before he began the instrumentation. That was the manuscript that he carried around Europe with him in 1928, working on it as he could, trying it out when he could find a willing and capable colleague. He orchestrated the two-piano score completely the following fall, and then cut out about four minutes of repeats and aggrandizements near the end before the premiere, though these are preserved in both the piano and orchestral manuscripts. An American in Paris was published in a version for solo piano by Gershwin’s long-time friend and musical associate William Daly in 1929, and in full orchestra score the following year, but Gershwin gave the two-piano score to Max Dreyfus, his publisher “and still my friend,” who kept it in his private collection. In 1944, Gregory Stone made a two-piano reduction of the orchestral score, and in 1980, the Labeque sisters recorded this version (and the Concerto in F), sent it to Ira Gershwin, George’s brother and lyricist, and expressed their desire to record more of his music. Four years later the original two-piano manuscript became available, and the Gershwin estate purchased it to include in the nearly complete archive of his manuscripts in the Library of Congress. The Labeques recorded for EMI it later that year, and it was finally published in 1986. ©2013 Dr. Richard E. Rodda