Comparative Contract Law Summary 1. Introduction to Contract law

advertisement

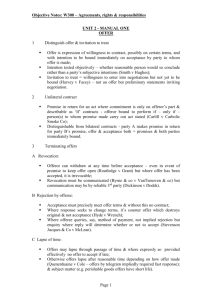

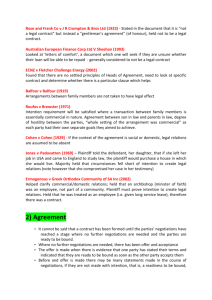

Comparative Contract Law Summary 1. Introduction to Contract law What is a contract? Germany § 311 BGB: A contract between the parties is necessary for the formation of an obligation relationship by a legal transaction … in so far as statute does not prescribe otherwise. Contract more correctly referred to as: • Contractual relationship of obligation = § 241 BGB (where a relationship of obligation exists, the person whom the obligation is owed is entitled to claim a performance from the person who owes the obligations). • Legal transaction • Declaration of intention Relationships of obligation by law: § 812 BGB, § 823 BGB and § 677 BGB: not based on voluntary agreement, but imposed by law Relationships of obligation by contract: § 311(1) BGB Specific rules §145 ff. BGB Precise and complete as to essential elements of the proposed contract 1 England • No uniform definition of contract • Contract is a promise or a set of promises, or an agreement which is enforced or recognized by law • Underlying concept: exchange / bargain Consideration Has not been developed by the court or the legislature. But it can be describe as an exchange of promises. Sufficiently precise and complete to amount to an undertaking to be bound if it is accepted – Scammell & Nephew Ltd v Ouston (1941) Nearly all definitions of contracts will generally emphasise three main elements: Agreement Intention to be legally bound = (parties must intend the agreement to be legally enforceable but not every agreement will be enforced by the law. made in domestic or social setting are not legally binding UNLESS it can be established that there was an intention to create legal relations. Commercial = the law will enforce commercial agreements, UNLESS there are clear words that indicate the contrary for instance, where the parties make the agreement ‘ subject to contract’, or ‘binding in honour only’. 2 Consideration: idea of reciprocity. Is in essence mean the act or promise given in exchenge for the promise. France Art. 1101 CC: A contract is an agreement by which one or several persons bind themselves, towards one or several others, to transfer, to do or not to do something. Art. 1108 CC: Four requisites are essential for the validity of an agreement: • The consent of the party who binds himself; • His capacity to contract; • A definite object which forms the subject-matter of the undertaking; • A lawful cause in the obligation. Juridical act = voluntary act that is intended to create legal relations, since a contract is a source of obligation that is founded on parties’ agreement. Contract = a contrast is an agreement that creates obligations But Convention: is any agreement based on consent and includes agreements to modify or terminate a contract or to transfer an obligation. A contract is therefore a sub-category of the larger category of convention. Rule the same for contract and convention THEREFORE: • contracts=agreements on consent of both parties • must have a definite object + lawful cause in obligation • art. 1126 further elaboration on concept of object (subject matter of the agreement) • art. 1131 further elaboration on requirement of cause (the reason, subjective or objective) The Netherlands 3 Book 6 = the law relating to contract Book 3 = the concept of a juridical act • Art. 6:213 DCC A contract in the sense of this title is a multilateral juridical act whereby one or more parties assume an obligation towards one or more other parties. Provides that ‘a contract… is a multilateral juridical act whereby one or more parties assume an obligation towards one or more other parties’ • Art. 3:33 DCC A legal act requires a will which is directed a will is directed towards a legal consequence and which has been manifested by a declaration. A juridical act requires an intention to produce juridical effects, which intention has been declared. Agreement of the parties and obligations imposed by law: art 6:162 ff., art. 6:212 ff., art. 6: 198 ff. Contract = sub-category of juridical acts Declaration of intention = a contract is made up of two declaration of intention: OFFER / CORRESPONDING ACCEPTANCE. By making an offer, the offeror manifest his attention to be bound by the terms of his offer once it is accepted by the offeree. The offeree declares his intention to be bound by accepting the offer. In this way, these two corresponding declarations of intention constitute the multilateral juridical act that is the contract. Why contracts are enforced? • Promissory theories – • Will theories – • You should keep your promise You intended to be bound Reliance theory 4 • – You induced another to rely on your undertaking to his detriment – Combination will and reliance theories Efficiency theory Everyone is better off if you keep your Basic principles: • Freedom of contract Everyone is free to decide whether to contract at all, with whom they are willing to contract and on what terms • Binding force/Sanctity of contracts contracts should be respected, upheld and enforced by the courts out of respect for voluntarily assumed obligations and the corresponding voluntarily created rights • Consensualism contract is not subject to specific formal requirements, unless prescribed by the law What is the role of contract law? • • • • • • Contract law defines how the practice of making agreements should be conducted: Has a contract been made? – Offer and acceptance – Intention to create legal relations – Consideration/causa – Formalities Can the contract be set aside? – Mistake – Misrepresentation / (Non-)Disclosure – Undue influence/Exploitation/Duress What are the respective rights and duties of the parties? – Interpretation – Supplementation • Legislative default rules • Good faith • Custom What remedies are available for breach of contract? – Breach of contract – Damages – Termination – Specific Performance Are there limits to the parties’ freedom of contract? 5 2.Contract Formation Contract formation is mainly based on the offer/ acceptance mode. It is accepted as the method for analysing contract formation in England, France, Germany and the Nlds. What is an offer? Germany Intermediate approaches Offer = declaration of intention, Specific rules §145 ff. BGB Precise and complete as to essential elements of the proposed contract Offer = declaration of intention, therefore the general provisions on declarations of intention and the specific rules on offers are applicable. The offer must state the essential elements of the proposed contract precisely and completely. The offer must be complete and definite. Declaration of intention is= a declaration that expresses an intention to bring about certain legal consequences. It expresses the intention to enter into a contract and to be legally bound. The Netherlands Intermediate approaches Offer : 6:217(1) BW = introduce the offer and acceptance model Offer = juridical act (see 6:218 BW) Art. 3:33 BW declaration of intention Art. 3.33 – 3.35 BW: establishes whether an offer has been made. Art. 3:37: to take effect, an offer must be communicated to the addressee. Art.6:227: provides that is must be possible to determine the content of the obligations assumed by the parties. An obligation is considered to be sufficiently determinable if its content can be determined according to criteria which can be indentified in advance. However, if a contract is concluded by offer and acceptance, and the acceptance is a mere’ yes’, then in order for a contract to be concluded, the obligation must be sufficiently determinate, hence be contained in the offer. France Subjective approaches Art. 1108 CC: agreement - ‘consent of the party’- no reference to the concept of offer. The formation of a valid contract requires ‘the consent of the party who commits himself’. Offer = proposition which includes all the elements of the proposed contract, must be precise and firm Concept of an offer (or acceptance) is not defined in the civil code. 6 Art. 1583 CC: in the case of sales contracts, the parties must have reached agreement on the thing to be sold and the price to be made. the offer to conclude a contract of sale must identify the thing to be sold and the price to be paid for it. England Objective approaches Offer = a statement expressing a willingness to contract on the terms stated as soon as those terms are accepted by the offeree Storer V Manchester City Council (1974) The offer must be communicated to the offeree Taylor v Laird (1856) Sufficiently precise and complete to amount to an undertaking to be bound if it is accepted – Scammell & Nephew Ltd v Ouston (1941) Contract is not concluded if terms are not clearly enough indicated that they indicated to be bound May &Butcher v R (1934) Can proposal made to the public be an offer? German law: Offer can be made to undefined group of persons Dutch law: no general rule, depend on circumstances French law: A proposal to the public generally will be treated as an offer English law: proposal to the public generally treated as an invitation to treat o BUT: Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co = that was an offer 7 Offer an invitation to treat Proposals to conclude a contract can be made to an individual, a group o person on the public at large. Proposal to the public = advertisements, poster, circular, price list, window displays, display of goods, on shop shelves or in vending machines, ect. the person making the proposal does not make an offer but invites the other party to do so. German law Advertisements, catalogues, displays in shop windows, menus – invitations to treat Display of goods on shop shelves – unresolved, probably invitation to treat Public proposal invitation to treat. Interest persons are requested to make an offer to the seller. Advertisements are treated as invitation to treat in order to avoid the consequence for the seller or offeror who could run out of the goods he is proposing to sell. The courts provide the offeror the opportunity to decide at a later stage whether and with whom he wants to conclude a contract. Dutch law Advertisements: no general rule, depends on circumstances Display of goods: offer, subject to proviso ‘While stocks last’ No general rule on whether a public proposal should be regarded as an offer or as an invitation to treat, this will depend on circumstances. The Dutch Supreme Court has decided that an advertisement concerning the sale of real property at a specified price will be regarded as an invitation to treat. The characteristics of the person with whom the contract is to be concluded are essential to the seller and further negotiations on the other conditions of the sale will be usually necessary. If the advertisement in a newspaper about a 50 € bikes, it is regarded as an offer because the characteristics of the buyer are not essential to the seller. The contract will be concluded with the first person who accepts the offer. Whether an advertisement is treated as an offer or an invitation to treat depends on when there is a need for further bargaining or whether the characteristics of the person contracting is essential. Catalogues and prices list offer because that are subject to the implied clause that the offer is valid”while stocks last”. (épuisement des stocks) French law Public proposals – offers which bind the offeror to the first acceptor But: if the offeror may need to know the identity of the offeree, invitation to treat Displays of goods in shop windows, shelves = offer, provided price displayed 8 Whether a proposal is an offer or an invitation to treat is a matter of fact to be decided by the courts in an individual case. The “Court de cassation” has laid down certain rules. the public proposal as a public offer. English law Advertisements, displays of goods in shops, catalogues, circulars, advertisements of auctions and requests for bids = invitations to treat Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists (1953) Partridge v Crittenden (1968) But:Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co (1893) = OFFER Public offers/ proposals invitation to treat Advertisement of a rewards an offer Display of goods Germany On shop shelves – unresolved, probably invitation to treat Uncertainty about invitation to treat/offer under German law It is the customer who makes the offer The Netherlands Normally regarded as an offer Offer subject to the proviso ‘while stocks last’ France In a shop window, shelves regarded as an offer as long as there is a price displayed. In self-service shop the sale is completed when the customer has placed the article in the basket (decision of Paris Court of Appeal). There is consensus between the parties and a contract is formed. England Display of priced goods in shop is invitation to treat Fisher v Bell Customer treated as making an offer, which the seller can accept or reject Contract is not completed until the customer has indicated the article which he needs and the shopkeeper accepts that offer Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists Ltd. Shop regarded as a place for bargaining, not for compulsory sales 9 Agreement Germany Intermediate approach Declaration of intention: -person must intend to act per se -an intention to act in a legally relevant way -person must intend to bring certain, specific legal consequences (§ 119 BGB: person who intend to make declaration but mistakes in relation to the specific consequences) § 122 BGB: protection of the party to whom declaration is made The Netherlands Intermediate approach Recognizes a combined will-reliance theory Offer must be sufficiently definite, containing all essential elements of an offer the contract The appearance of an intention to be bound will bind the maker of a declaration if it is reasonable for the addressee to rely on it being an offer France Subjective approach Take account of the actual state of mind of one of the parties Contractual obligation can only arise from the will of the person bound by it Agreement= as subjective meeting of two minds If party alleges he did not intend to be bound by the agreement he needs to make allegation plausible, but may be required to compensate the other party as result fo any loss suffered as a result on the basis of tort art. 1382 CC England Objective approach To determine whether agreement has been reached between the parties it is sufficient that one party reasonably thinks that the other party has agreed Storer v Manchester City Council (1974) Agreement must be clear and definite, otherwise contract is not binding Close relationship between two requirements: certainty and intention. It is not possible to have an intention to be bound when the content of the proposed agreement is not sufficiently certain 10 Effect of an offer Germany Offer = declaration of intention § 130 BGB ff. : becomes effective when it reaches the addressee. §130 BGB: a declaration of intention which is to be communicated to another person is effective, when made in the absence of the addressee of the declaration, at the point in time at which it reaches him. § 145 BGB: once the offer is effective, both parties are bound by it and the offeror is not permitted to revoke his offer. He will remain bound until the offer lapse. Period time = § 146 BGB provides that an offer loses effect or lapses if it is rejected by the offeror, or if it is not accepted in due time in accordance §§ 147 – 149 BGB. § 147 BGB = an offer that is made in presence of the offeree, may only be accepted immediately, unless the offeror fixes a time period within which acceptance of the offer can take place. (Telephone or other technical apparatus as well). Loses effects: The offer loses effect if they are not and no time period is given for acceptance. § 148 BGB = If the offeror fixes a time period for acceptance in the terms of the offer, this § provides that the acceptance may take place only within that period of time. § 149 BGB = provides that if an acceptance reaches the offeror belatedly, but it was in such a way that it would ordinarily have arrived in time (postmark), then the offeror, once he has received the acceptance, must notify the offeree of the delay. § 150 BGB (1) = provides that the acceptance will count as a new offer. If the acceptance contains amplifications, limitations or other alterations to the offer, it is also deemed to be a rejection of the offer and the purported accepted is treated as a counter offer.( § 150 BGB (2)) The Netherlands Offer = juridical act art. 3:37 (3) BW: becomes effective once it reaches the addressee. The addressee does not actually have to be aware of the content of the declaration in order for it to reach him. An offer thus takes effect when it reaches the offeree. Withdrawal an offer = once the offeror has sent the offer, he can prevent it from taking effect by withdrawing the offer. The withdrawal must reach the offeree before or at the same time as the offer. art. 3:37 (5) BW Loses effect = the offer loses its effect when it is accepted, because it has been subsumed by the contract which has been formed. Art. 6:221 (2): an offer loses effect if it is rejected by the offeror. When it reaches the addressee. (German and Dutch) 11 Art. 6:225: modification of the offer is treated as a rejection of the original offer and as a news one counter-offer. England Offer is not effective until it is communicated to the offeree, i.e. received • Unless withdrawal reaches offeree previously or at the same time Period of time: if the offeror fixes a period of time in the offer during which it can be accepted, the offer lapses if it has not been accepted by the end of that time period. If the offeror didn’t fixe the period of time for the acceptance in the offer, an offer will be normally be held to be open for a reasonable period of time. Manchester Diocesan Council v Commercial Investment (1969) Ramsgate Victoria Hotel CO v Montefiore (1866) When it enters his sphere of influence. France The offer must be communicated to the offeree in order to take effect. Period time = the offer lapses after the end of time fixed for acceptance. No time = fixed after a reasonable period. Revocation of an offer The Netherlands – Art. 6:219 (1) BW: an offer can be revoked. However, the revocation is no longer possible if the acceptance has been dispatched. Once it has been dispatched, the offeror can no longer prevent the conclusion of the contract. – Art. 6: 219 (2): where an offer is made with the statement that it is without obligation, the offer can still be revoked, even after the acceptance has been dispatched and even after the acceptance has reached the offeror. – – Exceptions: 1. Irrevocable during the fixed time stated for acceptance but not all the time art. 3.33 – 3.35 BW 2. Irrevocable if it is stated in the terms of the contract Nature of the offer 3. Irrevocable if is stated that it is an offer WITHOUT OBLIGATION. If the revocation has delay it is irrevocable – if not it is revocable even after acceptance has been dispatched. 4. Art. 6:220 BW = an offer of a ‘reward’ made for a fixed time can only be revoked for ‘important reason’. It is therefore in principle irrevocable. Offer without obligation Not revocable: once the acceptance of the offer has been dispatched. 12 France – In principle an offer may be revoked as long as it has not been accepted. – The offer cannot be revoked during the fiwed time for acceptance. – The offer must be kept open for a reasonable time for acceptance. if the offeror revokes his offer anyway, he will be held liable to pay damages for the loss the offeree has suffered from the revocation = art. 1382 CC tortious wrong Germany – – – – – § 145 BGB: once it took effect, an offer is in principle irrevocable unless the offeror states that it is ‘revocable’ or ‘subject to change’. § 130 BGB: the offer can be withdrawn or revoked provided it reaches the offeree prior to or at the same time as the offer itself. The offer is irrevocable until it lapses. Thus it is in the offeror’s interest to stipulate in his offer a fixed period of time for acceptance. The German approach is explained as being a “requirement of commerce”. The offeree must be able to rely on a contract being concluded when he makes a timely acceptance of the offer. Offer is binding unless offeror states, e.g.: • revocable offer • offer subject to change NB. Distinguish between revocation and withdrawal: – withdrawal: prior to or at same time as offer received – revocation: after offer has taken effect England – – – – – Every offer can be revoked at any time before it is accepted, every offer is revocable. The offeror is not bound by the offer. Even if the offer itself states that it is irrevocable or if it provides a fixed period of time for acceptance, the offer may nevertheless be revoked at any time before acceptance, without further consequences. Rationale: doctrine of consideration Exceptions: • Offers contained in a deed (signed written document attested by a witness. • Option contract (a separate contract made for a nominal amount, which holds the promisor to his offer. 13 Consideration: • • • A promise by one party which is not supported by consideration is generally not binding Basic concept: there is consideration for a promise if the promisor makes it in order to obtain a desired counterpart Reciprocity, bargain What is a consideration? Currie v. Misa (1875) LR 10 Ex 153 "consideration" is : “ a valuable consideration, in the sense of the law, may consist either of some right, interest, profit or benefit accruing to the one party, or some forbearance, detriment, loss or responsibility given, suffered or undertaken by the other." Example: In a contract for the sale of goods, the seller (S) promises to deliver the goods and the buyer (B) promises to pay for them on delivery – S’s promise to deliver the goods is consideration for B’s promise to pay for them – B’s promise to pay for the goods is consideration for S’s promise to deliver them Nature of the consideration: Consideration need not be ‘adequate’, i.e. of equivalent value, but it must be sufficient – something of value in the eyes of the law – Thomas v Thomas (1842) 2 QB 851 – Midland Bank & Trust Co v Green [1981] 1 All ER 153 – Chappell & Co Ltd v Nestle Co Ltd [1959] 2 All ER 701 – Mountford v Scott [1975] Ch 258 Is a fundamental requirement for the formation of a valid contract under the common law. The doctrine of consideration provides that a promise is only binding if there is a corresponding benefit to the promisor or detriment to the promise. It’s a promise to keep an offer open (not revoking it), therefore, requires consideration to make it binding and would thus only become so if the offeror obtains some benefit or the offeree incurs some detriment in return for the promise not to revoke the offer. Option contract: the offeror cannot revoke his offer. This means that the parties must enter into a separate contract to keep the offer open. The offeror needs to receive consideration for his promise to keep his offer open. In order for a revocation to take effect, notice of revocation must reach the offeree Byrne § Co v? Leon Van Tienhoven. The communication of revocation does not need to come from the offeror. It can be communicated by a reliable source Dickinson v. Dodds 14 Uniteral contract = an agreement to pay in exchange for performance, if the potential performer choose to act. Paying 1000 € for doing something: the performance is the acceptance. Errigton v. Erringhon and Woods (1952) = when the performance stated, the offer cannot be revoked. Daulai Ltd v. Four Millbank Nominess ltd (1978) 15 Acceptance When the acceptance became effective then the contract is concluded and it cannot be withdrawn without further consequences. England • • The offeree must communicate his acceptance to the offeror in order for the acceptance to have effect and for the contract to be concluded. Acceptance is communicated if it is brought to the notice of the offeror. When it reaches the offeror, it is concluded. • However, POSTAL RULE = When the acceptance is communicated via the post, the contract is concluded when the acceptance is dispatched. Adam v. Lindsell (1818) Harris’Case (1872) • The postal rule is not a general rule. It is limited to postal and telegram communication of acceptance and is subject to a number of restrictions. It only applies when a mode of communication has not being specified in the offer. If the better is sent too late, the postal rules don’t apply anymore. Holwell Securities Ltd v. Huges ( 1974) = an acceptance was posted to the offeror and was lost in the mail. The plaintiff argued that the postal rule applied. Russel Lj held taht since the offer contained the instruction that “notice of the acceptance must be given to the offeror, it followed from the words notice...to’ that the offeror be notified of the acceptance for it to have effect, even though the language of th offer suggested that communication of the acceptance could be made by post. Postal rule is exclude. Exceptions of the postal rule: 1. It does not apply when the terms of the offer specify that the acceptance must reach the offeror. 2. It probably does not operate if its application would produce manifest inconvenience and absurdity taking into account the circumstances of the case and the subject-matter of the contract. Byrne & Co. V. Leon van Tienhoven (1880) = postal rule is criticized because it may occur that the acceptance is posted prior to the receipt of a revocation. In that case, tje offeror no longer intends to conclude a contract with the offeree, but a contract has nevertheless been concluded. The postal rule does not apply to all forms of communication. There is a distinction between INSTANTENEOUS (telephone, telexes, faces, emails and electronic date exchange and NONINTANTANEOUS communication. Silence: is generally not regarded as acceptance even when the offer states that silence constitutes acceptance. 16 Brogden v Directors of the Metropolitan Railway CO (1877) acceptance may take the form of conduct. = Conduct will consist of acts of performance of the contract, for instance by delivering the goods that have been ordered. The offer may invite acceptance by conduct and waive the requirement of notification. Especially in UNILATERAL contract where acceptance usually takes the form of performance. ( Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co (1877) ) Germany An acceptance is also a declaration of intention. An acceptance must be communicated to the offeror. Takes effect when the declaration of intention comprising the acceptance reaches the offeror. For the acceptance to be effective, it is sufficient that it comes within the sphere of influence of the offeror. Silence: cannot in principle constitute an acceptance. However, and offeror must respond promptly to a counter-offer, otherwise he may be deemed to have accepted it. France When acceptance takes effect lies within the discretion of lower court. The “Court de cassation” has adopted the dispatch theory for the acceptance by letter. In one case, the court decided that where an offer was to be accepted within 30 days, and the offeree dispatched the acceptance 7 days prior to the expiry of this time period, the acceptance was ‘destinated to become perfect’ by its dispatch. Silence: silence does not constitution acceptance. When an offer is made in the exclusive interest of the addressee, the addressee’s silent implies acceptance. The Netherlands The acceptance is also a ‘juridical act”. It becomes effective when it reaches the offeror 3:37 BW Like other declaration of intention, the acceptance is effective 3:37 (3) For the acceptance to ‘reach’ the offeree, it is not necessary for the offeree to have actual knowledge of the acceptance. It is generally accepted by doctrine and case law that it is sufficient that the acceptance has arrives at the offeree’s address and that he could reasonably have acquainted himself with the content of the acceptance. Art. 6:224 combined with art. 3:37 (3): If the acceptance does not reach the offeror due to circumstances which can be attributed to his own risk, for example because he provided an incorrect address, then the contract is deemed to be concluded at the time that the acceptance would have reached him has the disruptive event not occurred. hence a ‘corrected actual receipt theory’ is applied = if an acceptance does not reach the offeror due to circumstances which can be attributed to his own risk, then the contract is deemend to be concluded at the time that the acceptance would have reached him if the disruptive (perturbateur) event had not occurred. 17 Silence: silence can under certain circumstance be regarded as acceptance. Offer and acceptance do not need to take place expressly but can occur in any form. can be regarded as acceptance in particular as a result of conduct that implied this acceptance/ the contract might be concluded by the performance of the required act. 18 3. Defects of consent England Netherlands France Germany Misrepresentation Common/mutual mistake Dwaling art. 6:228 BW Erreur art. 1110 Irrtum §119-120 Fraudulent misrepresentation deceit Bedrog art. 3:44 Dol art. 1116 Arglistige §123 Duress Bedreiging art. 3:44 Violence art. 1111 ff. Widerrechtliche Drohung §123 Undue Influence: - Actual - Presumed Misbruik omstandigheden 3:44 van art. Täuschung Wücher §138 We can distinguish three type of defect of consent: Mistake Fraud Duress Mistake England Types of mistake: a. Shared common mistake b. Non-identifical mistake (mutual mistake/misunderstanding) c. Unilateral mistake Shared common mistake • Both parties made the same mistake • Mistake can be seen to nullify consent • Mistake must be fundamental o Res extincta – mistake as to the existence of the subject matter of the contract o Res sua – mistake as to title o Mistake as to the quality of the thing? 19 • Quality forms part of the contractual description • Breach of contract • Misrepresentation Mistake as to quality • Generally will not avoid the contract • If the quality forms part of the description – breach of contract • If the quality is not part of the contractual description: mistake will not nullify consent • UNLESS: it relates to the substance of the subject matter and its absence makes the thing essentially different Non-indentical bicameral mistake • Misunderstanding, mutual mistake • Both parties made mistakes, but different ones • Mistake prevents parties from reaching an agreement • Mistake negates agreement Unilateral mistake • Only one party makes the mistake • If other party knows or ought to have known of the mistake, the contract is void • E.g. mistake as to the identity of the contracting party 1.Mutual or common mistake: both parties made the same mistakeagreed on same thing but their agreement cannot have its normal effect, mistake is said to nullify consent -mistakes to nullify consent are very limitedneeds to be fundamental shared mistake of fact, mainly as to the existence of the subject matter 2.Unilateral mistake: parties never agreed on same thing, either one party has made a mistake or both have made different mistakes -only allowed if it is caused by innocent or negligent misrepresentation Misrepresentation is another means of identifying mistake in English law, but mistakes caused by misrepresentation is another means of identifying mistake France • • Art. 1109 CC Art. 1110 CC Types of mistake: • Erreur sur la substance: mistake relating to the subject matter of the contract 20 • • • • • • Erreur sur la personne: mistake relating to the other party Erreur sur la valeur: mistake as to value? ‘Motif déterminant’ Excusable Knowledge of the other party not necessary Distinction between mistaken valuation and mistaken facts which form the basis for the valuation (mistake as to a substantial quality) Uses mistake as ground for relief Mistake= false assessment of reality made by contracting party Erreur-obstacle= If mistakes are really important that there has never been any agreement (obstacle to the formation of contract), concern the very nature or identity of the subject-matter of contract Art. 1110 CC: two main types of mistakes: relating to subject matter and relating to the other party -does not take into account how the mistake was caused -allows unilateral and induced mistakes The Netherlands Art 6:228 (2) BW: The nullification cannot be based on an error regarding a strictly future circumstance or an error which should remain for the account of the party in error, given the nature of the contract, common opinion or the facts of the case. Germany Mistake= incorrect understanding of the reality of the situation §119 and §120 BGB: mention different types of mistakes, rather unclear §119: two clauses: 1st: mistake in declaration or expression (meaning or content)- 2nd: mistake as to subject matter (judged by objective criterion) -includes the element of the parties’ reliance on contract Misrepresentation England Misrepresentation – 5 ingredient: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. A statement Specific existing and verifiable fact or past event Statement must induce the contract No knowledge that the statement is untrue Did the statement influence the representee’s decision? 21 Three types of misrepresentation: 1. Innocent: false statement with reasonable grounds to believe it was true 2. Negligent: false statement, no reasonable grounds to believe it was true 3. Fraudulent: false statement, knowledge of falsity, reckless whether or not true France The Netherlands England Fraud/ Deception • • • • English law: fraudulent misrepresentation France: art. 1116 Dol Germany: §123 BGB arglistige Täuschung Netherlands: art. 3:44 BW bedrog Fraud -least controversial of the defects ENGLAND fraud is not treated as general defect of consent since it is subsumed as an instance of misrepresentation person may complain if he was induced to conclude a contract by a fraudulent misleading statement FRANCE (dol) Art. 1116 CC: conditions of fraud to vitiate consent: fraud must have induced a mistake in the other party’s mind Difference between fraud and mistake= mistake concerns essential qualities of subject-matter, fraud may be invoked when resulting mistake would not have given the right to annul the contract if it had been spontaneously made fraud is not in itself defect of consent but the cause for such defect Requirements for contract to be annulled: proven that without fraud the aggrieved party would have entered into contract, deceiving party’s intention to deceive must be established and fraud must have been committed by a party to the contract -fraud can result from acts, lies (made on purpose to induce other party into contracting and sufficiently important) or fraudulent non-disclosure of material facts 22 GERMANY -very similar to French law §123 BGB: anyone who has been induced to make a declaration of will by fraudulent deceit may have this declaration annulled -fraud must result in mistake of the other party, but does not have to be fundamental -fraud by third party may lead to annulling the contractif other contracting party knew about the fraud or should have known (§123 BGB II) -less strict than French law mere knowledge suffices -three conditions: must have been deceit, due to acts or non-disclosure, deceit must be fraudulent and if a mistake has been caused by the fraudulent deceit, the mistaken party is relieved from paying the negative interest to the non-mistaken party, whose reliance is no longer deemed worthy of protection Coercion/ Duress • • • • England: Duress France: art. 1112 Violence Germany: §123 BGB widerrechtliche Drohung Netherlands: art. 3: 44 BW bedreiging Duress -less controversial than mistake since if illegitimate pressure has been exercised on one party by the other few would deny that relief should be granted -differences may lie as to what kinds of pressure may be considered illegitimate (economic) and in how far an what circumstances constrained party should be protected ENGLAND -duress and undue influence may be represented together under this category -both: consent of party to a contract obtained by form of pressure which law regards as illegitimate or improper Duress: common law defect of consent: actual or threatened physical vilence to the person of the contracting party or victim’s property or economic duress Economic duress: cases where contractual modification -all threats can be considered as a duress, when they leave the coerced party with no other reasonable alternative than concluding the contract -equity has added remedy in cases of undue influence, contrary to duress does not need violence -undue influence: where influence is acquired and abused, where confidence is reposed and betrayed Allcard v. Skinner (1887) 23 FRANCE -art. 1112 CC: violence prevents consent from being given freely, the person knows perfectly that he is making a bad bargain but has no other reasonable option because he has been threatened with worse -harm feared may be physical, moral or pecuniary -may be aimed at person who is to sign the contract or persons close to him -fear must be actual and serious enough to induce the victim to enter into the contract -contradiction in Civil Code whether the test must be objective or subjective, judges mainly chose subjective -constraint must be illegitimate -origin of the pressure may be diverse: may come from contracting party or third party, debate on whether the constraint may also arise from external circumstance in which plaintiff finds himself GERMANY -admits concept of illegitimate threat -§123 BGB: anyone whose declaration of will has been illegitimately induced by means of threat can have this declaration annulled -requirements to grant relief: there must be a threat, threat must be made to induce the victim’s declaration of will illegitimately, must have actually compelled the victim to make this declaration of will (subjective test applied) -§138 II BGB: exploitation of a person’s difficulty Exploitation/undue Influence/Unconscionable bargains English equitable doctrine • Two categories: – Actual undue influence • – Can actually prove party was induced to enter into contract through undue influence Presumed undue influence • Presumption that the party entered into the contract through undue influence because of the special relationship 24 Germany § 138 (2) BGB Legal transaction is void Illegality and Immorality Freedom of contract Underlying principles of contract law: o Freedom of contract o Binding force of contract – pacta sunt servanda Constraints on individual’s freedom of contract? Inherent tension between freedom and protection Illegality/immorality/public order and policy England – Illegality doctrine – A legal transaction which violates a statutory prohibition is void unless otherwise provided by the statute (§134 BGB ) – A legal transaction which violates public morals is void (§138 BGB) Germany • Pursant to Art.134 and 138 under German Civil Law, a contract which violates a statutory prohibition or good morals is void in most cases. This means that is the subject-matter of a contract is illegal or immoral, then it cannot be conclued and it is void. • §134 A legal transaction which violates a statutory prohibition is void unless a different consequence is to be deduced from the statute ]...] 25 • • § 138( 1) A legal transaction which is contrary to public policy is void. (2) In particular, a legal transaction is void by which a person, by exploiting the predicament, inexperience, lack of sound judgement or considerable weakness of will of another, causes himself or a third party, in exchange for an act of performance, to be promised or granted pecuniary advantages which are clearly disproportionate to the performance. • Surroygacy is not allowed in Germany. France – Art. 6: Statutes relating to public policy and morals may not be derogated from by private agreements – The agreement must have a lawful cause (art. 1108) – Art. 1131: “an obligation without cause or with a false cause, or with an unlawful case, may not have any effect” – Art. 1133: “a cause is unlawful if it is prohibited by legislation, where it is contrary to good morals or to public policy” – If the content of the contract is prohibited, the contract is invalid (“objet”) The Netherlands – Art. 3:40 (1): a juridical act which by its content or necessary implication is contrary to good morals or public order is void – Art. 3:40 (2): A juridical act which violates a mandatory provision is void, if however the provision is intended solely for the protection of one of the parties to a multilateral juridical act it is voidable Illegalilty/ good morals / public order Formation, method of performance or purpose of contract are illegal or contary to public policy Contract violates o interests of one of the contracting parties 26 E.g. Restraint of trade o interests of the community at large E.g. Contracts to commit crimes, contracts that are harmful to the administration of justice E.g. Contracts affecting basic principles of family life and sexual morality o interests of third party E.g. Contracts to defraud a third party 4. Remedies for breach of contract Remedies Damages Termination Specific Performance The legal systems will allocate detrimental consequences to the defaulting party if that party is in fault or carries the risk. The failure to perform may give the other party (the aggrieved party) certain rights against the defaulting party. The aggrived party may have the right to damages for the loss he suffers from the other party’s failure to effect due performance. Under certain conditions he may terminate the contract. Furthermore, the aggrieved party may have a right to specific performance, that is to claim that the contract be performed as agreed. All these three rights are called ‘remedies’. The situations where there is a failure to effect due performance which gives the aggrieved party one or more remedies are called ‘situations of non-performance’. 27 There is also the ‘duty of best efforts’: One party has to make his best effort in order to perform his obligation. However, in the case of a doctor, he does his best to cure his patient and even if he fails, there is still due performance as he made it with his best efforts. Excused Non-Performance: even the debtor who must achieve a specific result is not always liable in damages for non-performance. This is the case when he proves that the failure to perform was due to an impediment beyond his control. Then, the non-performance is excused as it is not his fault. 1. English Law Breach of contract = failure, without lawful excuse, to perform a contractual obligation. Refusal to perform, defective performance, late performance Mostly a standard of strict liability. When strict liability is applicable like in English law, the promisee must have received exact and precise performance of the contract otherwise, there is a breach of contract. ***A contract may stipulate a less strict liability (e.g. a doctor has to make his best efforts) 1) Damages • Primary remedy: every breach of contract gives rise to a right to damages monetary compensation for the loss caused by the breach or contract There must be no penalty stipulated in the contract in order to punish a breach of contract as the aim is not to punish the defendant but to compensate the claimant. A breach of contract is a civil wrong; it is not a criminal offence. Although punitive damages can be awarded in a tort action, they cannot be awarded in a purely contractual action, even where the defendant has calculated that he will make a profit from his breach of contract. 28 • Aim: put the claimant in the position which he would have been in had the contract been performed according to its terms. ‘Expectation’ or ‘performance’ interest The general rule is that an award of damages for breach of contract seeks to protect the claimant’s expectation interest. Case-law: “ Robinson v. Harman (1848) ” If no damage is caused by the breach of contract, nominal damages should be compensated (= small amount of money). • Causation There must be a direct causal link between the damages caused and the breach of contract. If the damages are caused by many different factors including the breach of contract, compensation may not be granted. • Remoteness of Damage The doctrine of remoteness limits the rights of the innocent party to recover damages to which he would otherwise be entitled. The principal justification for the existence of this doctrine is that it would be unfair to impose liability upon a defendant for all losses, no matter how extreme or unforeseeable, which flow from his breach of contract. The claimant can only recover in respect of losses which were within the reasonable contemplation of the parties at the time of entry into a contract. – Authorities • Hadley v Baxendale (1849) 9 Exch 341 • The Heron II [1969] 1 AC 350 “Where two parties have made a contract which one of them has broken, the damages which the other party ought to receive in respect of such breach of contracts should be such as damages which may fairly and reasonably be considered as arising naturally from the breach and damages which 29 may reasonably be supposed to have been in the contemplation of the parties as liable to result from the breach at the time of the contract.” • Mitigation of Loss A claimant is under a ‘duty’ to mitigate his loss. However, he does not incur any liability if he fails to mitigate it. The claimant is entirely free to act as he thinks fit but, if he fails to mitigate his loss, he will be unable to recover that portion of his loss which is attributable to his failure to mitigate. The aim of the doctrine of mitigation is to prevent the avoidable waste of resources. • Heads of damages: – Loss of bargain • Cost of cure = how much it is going to cost to compensate the damages. • Difference in value = if it is too complicated to compensate the damages, th difference in value/price can be payed. It is the difference between the market value and the value of the received object. – Reliance loss = to put the claimant in the position in which he would be if the contract had never been concluded. Restitution = to claim back what has been performed or payed Incidental losses = losses resulting from the breach of contract Consequential losses = not directly resulting from the breach of contract but is a consequence of it Disappointment, vexation, mental distress – – – – 2) Termination 30 • Termination discharges both parties from further performance of their primary obligations • Right to terminate depends on: – Nature of term broken – Consequences of breach Whether or not a contract is terminated, it is at the option of the parties. As long as the contract is still valid, both parties still have to perform their obligations although there was a breach of contract. In order to avoid performance, the contract must be terminated. • Distinction between: – Conditions – breach always gives the innocent party option to terminate contract and claim damages – Warranties – breach never gives the innocent party option to terminate contract; he can only claim damages – Innominate terms – innocent party can always claim damages and might also to terminate contract if the effect of breach is serious enough (it is some way between conditions and warranties: a mix of both). Conditions – Statute = when a statute provides that a particular term is a condition – Contract = when a condition is stipulated in the contract. The terms of the contract may contained that breach of contract would lead to the termination of it (e.g. ‘the time is the essence’) – Precedent = standard terms Warranty – subsidiary term Innominate term – terminated if breach deprives the innocent party of ‘substantially the whole benefit which it was intended he should obtain’ 3) Specific Performance • • • Secondary remedy discretionary remedy Equitable remedy at court’s discretion Order of the court that consitutes an express instruction to a contracting party to perform the actual obligations which he undertook in a contract • Available when damages inadequate (established by case-law): 31 Claimant cannot obtain satisfactory substitute, then no monetary compensation performance (e.g. land) Award for damages would be unfair to claimant (not valuable) Measure of damages difficult to assess (compensation difficult to estimate) Specific or ascertained goods (s. 52 Sale of Goods Act 1979) specific thing that cannot be compensate and has to be performed • Judicial discretion – granted only if just and equitable to do so • Refused in claimant has acted unfairly or dishonestly, or cause unfair hardship to defendant • Type of contract, no specific performance for: Contracts for personal services Building contracts 2. German Law • Reform 2002 the new German law of obligations entered into force = streamlined rules on remedies for breach of contract • German law does not speak about breach of contract but of ‘violation of obligations’ because the rules cover impediments not only to contractual but also to statutory obligations. The violation of obligation in the meaning of the new law includes all kinds of non-performance. – Defective performance = failure to perform at the time performance is due (either too early or too late), non-performance at all and violation of an accessory duty – Late performance = performance arrived too late – Failure to perform = non-performance at all Breach of ancillary duties 1) Specific Performance It is the first and primary remedy of the creditor. The debtor in many instances has a right to a second chance to perform. Thus most of the remedies are only available to the creditor after he has given notice of an additional period for performance. § 241. (1) By virtue of the obligation relationship, the creditor is entitled to demand performance from the debtor. Performance can also consist in an omission. 32 ‘The effect of an obligation is that the creditor is entitled to claim performance from the debtor § 275. (1) The claim to performance is excluded in so far as this is impossible for the debtor or for anyone. (2) The debtor can refuse performance in so far as this requires expenditure which is in gross disproportion to the creditor's interest in performance, having regard to the content of the obligation relationship and the requirement of good faith. When determining the efforts to be expected of the debtor, consideration must also be given to whether the debtor is responsible for the hindrance to performance. (3) The debtor can further refuse performance if he has to effect performance personally, and on balancing the hindrance to his performance, together with the creditor's interest in performance, the debtor cannot be expected to do this. §275 creditor has a right to performance, unless: – Performance is impossible – Performance will cause the debtor an effort which, contrary to good faith, is disproprtionate to the creditor’s interest in obtaining performance – Performance of a personal character 2) Termination The right to terminate the contract is a remedy at the choice of the creditor. There is no automatic termination of a contract. In order to terminate a contract, the aggrieved party only needs to tell the other party that it terminates the relationship, provided it has good cause to do so. The first prerequisite to terminate a contract is that there must be a violation of obligation, which need not to be a fundamental breach. Thus, the violation may consist of delay, delivery of defective goods, delivery of the wrong quantity, of a breach of an accessory duty, or total-non performance. If a performance has been defective, termination depends on the weight of the defect; minor defects do not give rise to the right of termination. • §326 BGB, if debtor is excused from performance under §275, his claim to counterperformance lapses 33 • Termination for breach of contract other than in case of impossibility: §323 and 324 • §323 BGB = in case of non-performance or defective performance, creditor can terminate provided additional time for performance has been fixed, and still no performance in accordance with contract A second chance must be given to the debtor (=additional time). The duration depends on the circumstances of the case. If there is still no performance, then the contract can be terminated. • Except: (additional period of time doesn’t make sense in those situations) • Performance impossible (§326 V) • Performance refused by debtor (§323 II, no. 1) • Damage has been done already (§324) • Further delay seems unacceptable (§323 II, no. 2. 3. 324) • Partial performance: termination of whole contract only if creditor has no interest in partial performance • Creditor may not terminate if responsible • §324: breach of ancillary (accessory) duty (=devoirs subsidiaires) not affecting performance, termination if creditor can no longer be reasonably expected to accept performance. At termination, both parties are released from their obligations Both parties have the right to recover money paid, property supplied and other means of performance or counter-performance. 3) Damages The aggrieved party may ask for damages under new law. Like the right to terminate a contract, the right to damages may also arise from all kind of violations. However, rules on damages differ slightly depending on kind of violation and kind of damage suffered. • §280 I: General principle = damages for violation of obligation must be imputable to the debtor Notion of fault important = imputable to the debtor + each party is held responsible only for his own intentional or negligent acts (=faults). 34 In contrast with English law, strict liability is applied. However, there is a presumption of fault. The debtor has to prove that the failure or defect in performance was not imputable to him. He bears the full burden of proof. • Different types of damages: 1. damages in lieu of performance §280 III – additional requirements of §281, 282, 283 – – – §281: defective or delayed performance §282: violation of ancillary duty (accessory duty) §283: performance impossible under §275 2. damages for delay = The creditor may ask for compensation when the debtor didn’t perform his obligation even after the additional period of time. • • Debtor’s duty to perform remains unaffected §280 II – additional requirements of §286 – Due date for performance arrived – Special warning (second chance by the creditor) – Still no performance 3. ‘simple’ damages = it concerns only compensation for the loss the creditor suffered because he did get the performance at a later stage. Falls under §280(I) BGB - Loss caused by violation of obligation Fault of debtor e.g. consequential loss 35 3. French Law In France the term ‘inexécution’ covers both non-performance and “remedyless” failure to perform. In case of a debtor’s non-performance, the creditor may claim specific performance. Damages Article 1147. A debtor shall be ordered to pay damages, if there is occasion, either by reason of the nonperformance of the obligation, or by reason of delay in performing, whenever he does not prove that the nonperformance comes from an external cause which may not be ascribed to him, although there is no bad faith on his Article. Article 1148. There is no occasion for any damages where a debtor was prevented from transferring or from doing that to which he was bound, or did what was forbidden to him, by reason of force majeure or of a fortuitous event. 36 Article 1149. Damages due to a creditor are, as a rule, for the loss which he has suffered and the profit which he has been deprived of, subject to the exceptions and modifications below. Mental distress or lost reputation (dommages morales) are recoverable. The starting point of French law for the assessment of damages is that the injured party should receive full compensation. Art. 1149 CC allows recovery of both losses incurred and profit denied as a result of breach. Termination In principle, French law does not allow a party to a bilateral contract to terminate it on the ground of the other’s non-performance, but if it is serious enough he may ask the court to do so (it is at the courts’ discretion). 4. Dutch Law Failure to perform will prevent the debtor from exercising any remedy. Article 6:74. 1 Every failure in performance of an obligation shall require the obligor to repair the damage which the creditor suffers therefrom, unless the failure is not attributable to the obligor. Article 6:75. A failure in performance cannot be attributed to the obligor if it is neither due to his fault nor for his account pursuant to the law, a juridical (legal) act or generally accepted principles. The aggrieved party may terminate the contract, reduce or withhold his performance even in cases where the defaulting party is not liable in damages. However, under Art.6:74, the aggrieved party cannot claim damages if the failure is not attributable to the debtor. The debtor is always excused in case of force majeure. 37 5. Content of the contract and the limits of freedom of contract Contract interpretation THE INTERPRETATION, IMPLICATION AND SUPPLEMENTATION OF CONTRACTS IN ENGLAND AND THE NETHERLANDS – notes The problem: contracting parties often lack the necessary information to foresee every contingency or they do not have the time, money or inclination to negotiate the allocation of rights and obligations for every situation. Contracting parties therefore leave matters unsettled. Solution: In order to identify the totality of rights and duties contained in the contract, the courts use processes of interpretation, implication and supplementation to discover the express, implied and supplemented terms of a contract. The express content of the contract Step 1: Identify the content of the agreement expressly concluded between the parties through a process of interpretation. Interpretation attaches a meaning to the terms contained in the contract and determines their legal effect. This process is to be distinguished, at least in theory, from the supplementation of the contract with duties from sources external to the parties’ agreement. In general, interpretation o a contract can start from either of two opposing perspectives: Subjective approach interpretation approached from the perspective of the contracting parties; limitations: it is difficult to discover with any certainty what a contracting party actually had in mind when making the contract, it must be proven that this understanding was common to both parties Objective approach perspective of an objective third party who determines the meaning of the contractual document England GENERAL: Objective nature Interpretation focuses on the objective meaning to be given to the contractual document and no the actual intentions of the parties Expression of intention rather than the intention itself Evidence of actual intentions are irrelevant It is the contractual language used by the parties rather than their actual intentions that determines the content and nature of their rights and duties The object of interpretation is to ascertain the meaning the contract would convey to a reasonable person Change from textualism to contextualism 38 CLASSICAL APPROACH TO INTERPRETATION: Traditionally: words in a contract where exclusively determined by focusing on the objective meaning of the words contained in the agreement judges had to give those words their ‘plain, ordinary and popular sense’- the meaning the ‘ordinary speaker of English’ would give to the words ‘canons of construction’ which were developed as ‘pointers’ to assist the interpretive process was applied when language of the contract is unclear or ambiguous Contract should be interpreted as a whole; the contra proferentem rule1 Literal approach to interpretation can at times lead to harsh results that do not justice to the bargain struck between parties MODERN DEVELOPMENTS Ignoring the context within which words are used can lead to an interpretation that defeats that expectations of the contracting parties Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd v West Bromwich Building Society the task of the court is to establish the meaning the contractual documentary document as a whole would ‘convey a reasonable person having all the background knowledge which would reasonably have been available to the parties in the situation which they are at the time of the contract’ The meaning of contract must always be determined against the relevant background New approach: dependent upon concentric circles working outwards, ever increasing in scope: word, phrase, sentence, paragraph, clause, section of contract, whole contract, surrounding factual matrix, legal and commercial context’ Giving a meaning to the contractual language However, evidence of actual intentions concerning the meaning the parties gave to the words contained in their contract is still excluded Parties positions are continuously changing during the negotiating period and only the final contract reflects the consensus reached between the contracting parties contract interpretation highly objective JUSTIFICATION FOR THE OBJECTIVE APPROACH The focus is on the meaning of the contractual document and not the actual intentions of the parties There are two main justifications for this approach: o It promotes certainty, which is seen to advance the interests of trade and serves the needs of commerce; it enables advisers and draftsmen to be more confident about the meaning of contracts; provides the contracting parties with an incentive to maximize clarity in their contracts; commercial contracts often connected to other contracts, third parties involved only have the contractual document to consider objective approach preferred o Reason of convenience and expediency; it facilitates quick and relative inexpensive judicial rulings E.g. A word has two meanings, one which validates the contract and the other which renders it void the court should choose the meaning that validates the contract 1 39 The Netherlands GENERAL: Underlying the interpretation of all contracts is the principle of good faith Art. 6:248 BW requires all contracting parties to perform their contracts in accordance with that principle It is possible through interpretation to shape the behavior of the contracting parties and achieve a fair and just outcome Not very often used, instead Hoge Raad has developed certain standards for interpretation: o Haviltex standard for contracts in general o The objective (CAO) approach for certain types of contracts involving third parties The Haviltex and the objective (CAO) approach should not be seen as rivals, but rather that there is a smooth transition between them Approach adopted depends on the nature of the contract involved: o Where the contracting parties are themselves directly involved in the negotiation and conclusion of the contract, the parties’ expectations and justified reliance appear to be best served by adopting the Haviltex approach o If the contracting parties are not directly involved in the negotiation of the contract and consequently cannot influence the content of the contract the objective (CAO) approach adopted to interpretation that promotes certainty and uniformity THE HAVILTEX STANDARD The Hoge Raad rejected in this judgment a purely literal approach to the interpretation of contract as well as interpretation exclusively based on the subjective intentions of the parties Interpretation of a contract is made subject to the will-reliance theory (Art. 3:33 and Art 3:35 BW) and the principle of good faith (art 6:248 BW) The court adopts the perspective of the contracting party (instead of the objective third party) Combination of subjective and objective elements Haviltex standard can be applied to either Subjective application: o Tries to reveal whether the parties share a common understanding with respect to the meaning of the terms contained in the contract o When shared common understanding lacking the reliance element introduced (art. 3:35 BW) to the interpretation of the contract o A contracting party is bound by a meaning given party is bound by a meaning given to his declaration of intention, even if it does not reflect his actual intention, if the other party was justified in attaching that meaning to the declaration o The justified reliance of each party on the meaning he has given to the contract and the justified reliance that the other party meant the same is protected. 40 o Reflects an attempt to balance the contracting parties’ actual intentions with the expectations raised by the acts of communication o The text of a contract is not determinative the context in which the agreement was reached needs to be considered o Circumstances that are considered relevant to determining the meaning to be given t the contract according to the Haviltex standards : Statements made by the parties Preliminary negotiations Subsequent conduct of the parties in perforimg the contract The nature and purpose of the contract The course of dealing between the partie Meanings commonly attached to similar provisions (technical terms) Usage The social circles to which the parties belong The degree of legal konledge possessed by the parties Whether they have had legal or technical assistance Examples of cases when the Haviltex standard, could be applied, albeit objectively: o General conditions o Insurance policies o Third party clauses The (subjective-objective) Haviltex standard is not applicable to all contracts THE OBJECTIVE (CAO) STANDARD In particular refers to collective employment contract (CAO) The CAO contracts used to give a grammatical interpretation, now is more of a reasonable interpretation according to objective standards Evidence of actual intentions are completely excluded if they cannot be derived from information that is verifiable for third parties (e.g. explanatory memorandum attached to the contract) The parties to such agreements, are not present during the negotiations are therefore lack the background information that could shed light on the nature of the rights and duties contained in the contract (only the text of the contract and other publically available information to rely on) Exception to the above: trust deeds, contracts concerning the transfer or real property, arbitration regulations, retirement fund regulation in the relationship employee – retirement fund a mere fact that a contract has a consequences for third parties does not on its own justify the application of this objective (CAO) approach – the nature and purpose of the contract must be taken into account CONCLUSION 41 It is possible to start the interpretation process from two opposing perspectives, interpretation can be either approached from: o The perspective f the contracting parties – reveal the actual intentions (subjective approach) o The perspective of an objective third party who determines the meaning of the contractual document (objective approach) The interests the law pursues are influential to determine which approach should be used: o ENGLISH LAW: the perspective of an objective third party (reasonable person) o DUTCH LAW: the interpretation combines elements of subjective and objective interpretation with the perspective of the contracting parties (who are treated as being reasonable); emphasis on giving effect to the spirit of the contract and realizing the (reasonable) expectations of the parties, so that a shared common understanding can be discovered; however if such a shared understanding is lacking the court will endeavor to protect the reliance that has been created as a result of the expression of intention contained in the contractual document Pursue certainty or the parties’ intentions/expectations influence the nature of (extrinsic) evidence that is considered to be relevant to the interpretive exercise: o ENGLISH LAW: where certainty, predictability and the responsibility of the parties for the content of their contract prevails the court will engage in an inquiry into what the parties intended with their contract; the nature of contextual information that is permitted to inform the interpretation process still reflects a need for certainty and objectivity; courts will only reply on objective and verifiable information to determine what the parties agreed upon o DUTCH LAW: courts attempt to give effect to the parties (reasonable) expectations and subsequent conduct which shaped those expectations; however to the extent that this type of evidence is not verifiable to third parties it would also seem to be irrelevant to the interpretation of contracts that are subject to the objective (CAO) standard CONTENT AND INTERPRETATION OF THE CONTRACT Problems: How do courts determine what the parties have agreed upon? Solution: traditional distinction: subjective vs. objective methods of interpretation Subjective approach: taking the perspective of the parties themselves Objective approach: taking the external perspective (i.e. third party position) SUBJECTIVE APPROACH IN DIFFERENT LEGISLATIONS: FRENCH LAW: 42 Art. 1156 CC – one must in an agreement seek what the common intention of the parties was, rather than pay attention to the literal meaning of the words GERMAN LAW: §133 BGB – when interpreting a declaration of intention, the actual intention is to be ascertained rather to the literal meaning of the expression ENGLISH LAW: Objective stance External phenomenon of expression rather than subjective intention of the parties Legal certainty SHORTCOMINGS OF SUBJECTIVE APPROACH ‘Intention’ – psychological phenomenon, difficult to verify Once a dispute arises, it is difficult to prove that the parties shared a common understanding That is why the objective elements are often introduced OBJECTIVE INTERPRETATION: REASONABLE PERSON FRENCH LAW: How would the term normally have been understood in that particular context by a reasonable person? ENLGLISH LAW: ‘The meaning which the document would convey to a reasonable person having all the background knowledge which would be reasonably available to the parties in the situation in which they were at the time of the contract’ Investors Compensation Scheme Ltd v West Bromwich Building Society (1988) OTHER OBJECTIVE APPROACHES ENGLISH LAW: Plain and ordinary meaning (i.e. literal or grammatical meaning) GERMAN LAW: §157 BGB – contracts are to be interpreted as required by good faith and having regard to common practices (i.e. normative interpretation: the role of good faith) RECAP OF THE ABOVE: 1. Aim interpretation: establish legal meaning of parties’ agreement 2. Traditional distinction: subjective vs. objective approach 43 3. Subjective approach: perspective of the contracting parties themselves 4. Objective: external factors a. Reasonable person b. Literal or plain meaning c. Open norms: good faith SUPLEMENTATION OF THE CONTRACT: Freedom of contract: the parties decide the terms of their agreement Problem: what if the contracting parties do not provide for a particular situation in the terms of their contract? Solution: look to other sources to fill the gap Examples of reasons for why the parties leave gaps in contracts: Parties lack ability to predict future It is too costly to write detailed contracts Reliance on the law SUPLEMENTARY SOURCES DUTCH LAW: Art. 6:248 (1) BW – A contract contains the legal effect agreed to by the parties and the rights and duties, which according to the nature of the contract, stem from legislation, custom, and the requirements of reasonableness and equity FRENCH LAW: Art. 1135 CC – Agreements are binding not only as to what is therein expressed, but also as to al the consequences which equity, usage of statute give to the obligation according to its nature TIME OF PERFORMANCE ENGLISH LAW : Sale of goods act 1979 s. 29 – within reasonable time FRENCH LAW: Art. 1901 CC – creditor may demand performance at once GERMAN LAW: §271 BGB – immediately, subject to good faith (§242 BGB) 44 DUTCH LAW: Art. 6:38 – immediately PLACE OF DELIVERY GERMAN LAW: §269 BGB – place where debtor has his residence DUTCH LAW: Art. 6:41 (b) BW – place where debtor has his residence Art. 6:41 (a) BW – in case of sale of goods, where goods situated ENGLISH LAW: Sale of Goods Act 1979 s.29 (2) - in case of sale of goods, where goods situated FRENCH LAW: Art. 1247 (1) CC - in case of sale of goods, where goods situated Exclusion clauses The role of good faith Default rules vs. Mandatory law Default Rules: Apply unless parties have made their own arrangements in the terms of the contract Facilitative functions – assists parties to conclude contracts Can be recognized in a contract by :‘unless otherwise agreed’ Mandatory Rules: Contracting parties may not deviate from these rules Controlling function – protect certain interests and (third) parties Can be recognized in a contract by: ‘shall’ CUSTOMS Customs established between contracting parties within a particular trade, industry or business community Repetitive behavior Conviction among the members of the relevant group that the behavior is required by law 45 GAP FILLINF BY THE COURTS DUTCH LAW: Art. 6:248 (1) BW – supplementing function of good faith GERMAN LAW: §242 BGB – supplementing function of good faith FRENCH LAW: Art. 1135 CC – supplementing function of good faith ENGLISH LAW: Terms implied by courts: Terms implied in facts: o Solutions for individual contracts based on parties’ presumed intention Terms implied in law: o Solutions for all contracts of a particular type based on wider policy considerations SUMMERY Express terms agreed by parties interpretation Fill in the gaps: o Legislation o Customs o Good faith, open-ended norms FREEDOM OF CONTRACT Underlying principles of contract law: o Freedom of contract o Binding foirce of contract – pacta sunt servanda The above can be found in Numerical Registering Co v Sampson (1875) LIMITS TO THE FREEDOM OF CONTRACT Issues: Constraints on individual’s freedom of contract? Inherent tension between freedom of contract and need to provide protection ILLEGAL CONTRACTS AND CONTRACTS CONTRARY TO PUBLIC ORDER OR POLICY 46 Formation, method of performance or purpose of contract are illegal or contrary to public policy Open and direct interference with individual’s freedom of contract justified because: o Contract violates interests of one of the contracting parties o Contract violates interests of the community at large o Contract violates interest of third party Courts will not assist parties to a contract which illegal or contrary to public policy by enforcing it GERMAN LAW: §134 BGB and §138 BGB FRENCH LAW: Art. 1131 and Art. 1133 CC – lawful cause DUTCH LAW: Art. 3:40 BW ENGLISH LAW: Illegality doctrine REGULATED CONTRACTS Freedom of contract – parties decide on the terms of contract Emergence of tightly regulated contracts o E.g. residential leases, employment contracts, consumer transactions Protective measures to safeguard interests of ‘weaker party’ Mandatory provisions restricting freedom of contract STANDARDIZED CONTRACTS Contract law based on idea that contracts are agreement is reached through negotiation But: contracts frequently are not the result of true negotiation Sets of standard terms and conditions Need for legal control By product of industrialization – mass transactions Facilitate conclusion of contracts Often used to shift the allocation of risks Why do contracting parties accept standard form contracts? o Economic superiority o Transaction costs 47 RECAP – CONTRACT LAW Contract law defines how the practice or making agreements should be conducted: o Has a contract been made? Offer and acceptance Intention to create legal relations Consideration/causa Formalities o Can the contract be set aside? Mistake Misinterpretation/non-disclosure Undue influence/exploitation/duress o What are the respective rights and duties of the parties? Interpretation Supplementation Legislative default rules Good faith Custom o What remedies are available for breach of contract? Breach of contract Damages Termination Specific performance o Are there limits to the parties’ freedom of contract? 48 6. Contract in historical perspective What is a contract in Roman Law? Why were contracts enforced in Roman Law and later? Contract formation The role of consensus Additional requirements Mistake Coercion/duress 49