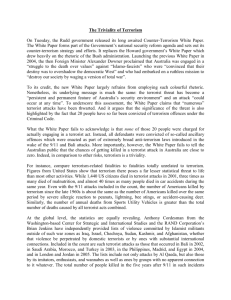

The Australian Government's anti-terrorrism

advertisement