Leadership is Theatre - NMSU College of Business

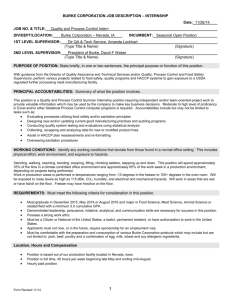

advertisement