Replace This Text With The Title Of Your Learning Experience

advertisement

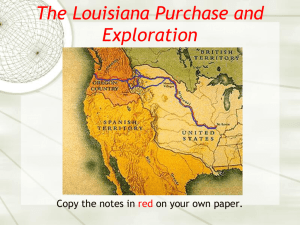

Exploring with Lewis and Clark Shelly Hott Graymont Grade School Summer 2009 Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. Students will walk through the Lewis and Clark expedition from start to finish looking at various primary sources and considering the following questions: Why were Lewis and Clark sent on the expedition? Why was it so secretive? What was the perspective of the people in the expedition of the land they were exploring? What was the perspective of the native Americans of the land the expedition was exploring How did the expedition affect the future of the United States? How did the expedition affect the future of the Native Americans who lived in the area explored? Overview/ Materials/Historical Background/LOC Resources/Standards/ Procedures/Evaluation/Rubric/Handouts/Extension Overview Objectives Recommended time frame Grade level Curriculum fit Materials Back to Navigation Bar Students will: Gain factual knowledge of the Lewis and Clark expedition Consider different points of view of the expeditions (those in the expedition and the native Americans living in the area being explored) Infer how the expedition affected the futures of both Native Americans and the United States 5 class periods 5th-6th Social Studies, U.S. History Textbook: Our Nation – Macmillan/McGraw-Hill or another textbook or book about the Louisiana Purchase Projector/computer Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Screen Whiteboard or flipchart and marker Map of the United states – preferably showing the Lewis and Clark route Handouts of 5 areas of comparison (see handout pages) Library of Congress: Fill up the Canvas … Rivers of Words: Exploring with Lewis and Clark Library of Congress: Rivers, Edens, Empires: Lewis and Clark and the Revealing of America Written document analysis sheet Map analysis sheet Photograph analysis sheet Illinois State Learning Standards Back to Navigation Bar Social Sciences: GOAL 16: Understand events, trends, individuals and movements shaping the history of Illinois, the United States and other nations. 16.A. Students who meet the standard can apply the skills of historical analysis and interpretation. 16.A.2c Ask questions and seek answers by collecting and analyzing data from historic documents, images and other literary and nonliterary sources. 16.B. Understand the development of significant political events. 16.B.2d (US) Identify major political events and leaders within the United States historical eras since the adoption of the Constitution, including the westward expansion, Louisiana Purchase, Civil War, and 20th century wars as well as the roles of Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. STATE GOAL 17: Understand world geography and the effects of geography on society, with an emphasis on the United States. 17.A. Students who meet the standard can locate, describe and explain places, regions and features on Earth. 17.A.2b Use maps and other geographic representations and instruments to gather information about people, places and Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University environments. Procedures Back to Navigation Bar Prior to beginning this lesson, students should be familiar with the events surrounding the Louisiana Purchase. We will do this by reading Ch. 12 Lesson 2 – The Louisiana Purchase. This lesson ends with a primary source containing an excerpt from The Journal of Captain Meriwether Lewis. This will serve as our introduction to the lesson. (Any similar book or textbook would work as well) Day One: Students will be introduced to the four questions that will be considered as we walk through the Lewis and Clark expedition: 1. Why were Lewis and Clark sent on the expedition? 2. Why was it so secretive? 3. What was the perspective of the people in the expedition of the land they were exploring? 4. What was the perspective of the native Americans of the land the expedition was exploring? These questions will be written on the board or on a flipchart (somewhere they can be kept, along with the ideas presented by the class) The flash video Fill up the Canvas Rivers of Words: Exploring with Lewis and Clark will be presented using a projector/computer Each topic should be looked at in order – at the end of each topic, students should discuss what was presented and consider whether it gives any information to answer any of the questions on the question chart. As appropriate, locate on the U.S. map where the expedition currently is. All primary sources can be looked at in their entirety – as time permits feel free to look more closely at any that seem of particular interest to the students. The following topics should be completed the first day: 1. Mission and Preparation Jefferson’s proposal to Congress Lewis plans from Harper’s Ferry Boat building problems Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Lewis learns more Dr. Rush advises An invitation Jefferson’s instructions to Lewis Louisiana Purchase 2. Winter in Saint Louis Jefferson sends Missouri map Jefferson advises Lewis Lewis describes Osage Apple Lewis sends specimens to Jefferson Expedition departs Wrap-up discussion and save what was added to the chart of questions. Day Two: Briefly review what was discussed the previous day Continue with the flash presentation beginning with point 3 on the map – continue discussion and adding to the chart of questions. Cover the following entries today: 3. First council with Indians 4. Sergeant Floyd dies 5. First buffalo is killed 6. At the Sioux Camps 7. Prairie Dog Description 8. Lewis continues to describe the area… 9. Council and near run-in with the Teton Sioux 10. Winter in Fort Mandan October 26, 1804 journal entry November 2, 1804 journal entry November 3, 1804 journal entry November 5, 1804 journal entry February 11, 1805 journal entry March 29, 1805 journal entry April 3, 1805 letter from Clark to Jefferson April 4, 1805 journal entry April 7, 1805 Letter from Lewis to Jefferson Wrap-up discussion and save what was added to the chart of questions. Day Three: Briefly review what was discussed the previous day Continue with the flash presentation beginning with point 11 on the map – continue discussion and Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University adding to the chart of questions. Cover the following entries today: 11. Bear description 12. First view of Rockies 13. Lewis makes a decision 14. Lewis scouts ahead of main party and encounters the Great Falls of the Missouri 15. Lewis goes up Lemhi Pass and looks west, but sees more mountains 16. Meeting the Nez Perce and ascent into the Bitterroots 17. Description of the Nez Perce 18. Entering the Columbia River 19. Maneuvering the Falls of the Columbia 20. Fort Clatsop Arriving at the Pacific Winter 1805-1806 Lewis writes about plants and animals Homeward bound Wrap-up discussions and save what was added to the chart of questions Day Four: Introduce Rivers, Edens, Empires Lewis & Clark and the Revealing of America using the introduction information. Divide students into 5 groups Hand out the 5 sets of handouts (Discovering Diplomacy, Geography, Animals, Dressed in Courage, Plants) one to each group (if desired, this could be done online with students looking at their section) Have students analyze and discuss their set of sources and develop a chart of similarities and differences in how the members of the expedition and the native Americans viewed their particular area of focus Have each group share their finding with the class. Day 5 Review discussions of the last 4 days and have all question charts and day 4 similarities and differences within view. Based on the finding of the past 4 days, have students consider and discuss the following Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University questions: How did the expedition affect the future of the United States? How did the expedition affect the future of the Native Americans who lived in the area explored? Evaluation Back to Navigation Bar Students will be evaluated in four areas using the rubric: 1. Respect for classmates: appropriate discussion rules should be followed 2. Understanding of topic: are students able to recognize the relationship between the primary documents and the questions being considered 3. Map skills: can students locate on a current US map, where the historical events took place 4. Historical thinking: are students able to analyze and compare different viewpoints based on various primary sources being considered Extension Back to Navigation Bar Students will choose one of the primary sources that were considered in the interactive map and do a more in-depth analysis on it using the appropriate analysis form. Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Historical Background Back to Navigation Bar Thomas Jefferson made the Purchase of the Louisiana Territory in 1803. In January of 1803 he secretively requested Congress for permission to explore this territory. The reason for the request being secretive was not to prevent Britain, France and Russia from being aware of it, but to keep it from Jefferson’s enemies in the Federalist party. Jefferson chose his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis to lead this expedition based on his intelligence and skills as a frontiersman. Lewis then chose William Clark (a draftsman and even stronger frontiersman) to co-lead the expedition with him. Together they put together a “Corps of Discovery” consisting of 42 men, about half of whom were soldiers; the rest trappers and scouts. They were charged with mapping the route from the Mississippi to the Pacific while making note of plant and animal life along the way. They were also charged with making note of what tribes of Indians they encountered, where they were located, their number, what type of trading would be available, their culture, etc. The journey took two years (1804-1806) and was successful in navigating a route to the Pacific while mapping the area, interacting with Native Americans, and collecting various specimens which were sent back to Jefferson. Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Primary Resources from the Library of Congress Back to Navigation Bar Image Citation Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. URL http://memory.loc.gov /cgibin/query/r?ammem/g md:@filreq(@field(N UMBER+@band(g41 27l+ct001114))+@fie ld(COLLID+dsxpmap )) Fill up the Canvas Rivers of Words: Exploring with Lewis and Clark – Flash Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/te achers/classroommate rials/presentationsand activities/presentation s/lewisandclark/ Fill up the Canvas Rivers of Words: Exploring with Lewis and Clark - Resources Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/te achers/classroommate rials/presentationsand activities/presentation s/lewisandclark/resour ces_toc.html Rivers, Edens, Empires – Lewis & Clark and the Revealing of America – Exhibition Rivers, Edens, Empires – Lewis & Clark and the Revealing of America - Sources Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/ex hibits/lewisandclark/l ewis-landc.html Library of Congress http://www.loc.gov/ex hibits/lewisandclark/l ewis-object.html Description Discovering the legacy of Lewis and Clark : bicentennial commemoration 2003-2006 / preparation route source: Frank Muhly. Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Rubric Back to Navigation Bar 4 3 2 1 Respect for classmates All statements, body language, and responses were respectful and were in appropriate language. Statements and responses were respectful and used appropriate language, but once or twice body language was not. Most statements and responses were respectful and in appropriate language, but there was one sarcastic remark. Statements, responses and/or body language were consistently not respectful. Understanding of Topic Clearly understood the relationship between the primary source and the questions being considered Somewhat understood the relationship between the primary source and the questions being considered Contributed, but did Did not contribute to not show an the discussion understanding between the primary source and the questions being considered Map Skills always able to locate on the current US map the location being discussed for the expedition usually able to locate on the current US map the location being discussed for the expedition sometimes able to locate on the current US map the location being discussed for the expedition Historical Thinking – Comparison of viewpoints Every idea/opinion was well supported with several relevant facts, statistics and/or examples. Every idea/opinion was adequately supported with relevant facts, statistics and/or examples. Every idea/opinion Every idea/opinion was supported with was not supported facts, statistics and/or examples, but the relevance of some was questionable. CATEGORY not able to locate on the current US map the location being discussed for the expedition Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Handouts Back to Navigation Bar Introduction When Thomas Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark into the West, he patterned their mission on the methods of Enlightenment science: to observe, collect, document, and classify. Such strategies were already in place for the epic voyages made by explorers like Cook and Vancouver. Like their contemporaries, Lewis and Clark were more than representatives of European rationalism. They also represented a rising American empire, one built on aggressive territorial expansion and commercial gain. But there was another view of the West: that of the native inhabitants of the land. Their understandings of landscapes, peoples, and resources formed both a contrast and counterpoint to those of Jefferson's travelers. This part of the exhibition presents five areas where Lewis and Clark's ideas and values are compared with those of native people. Sometimes the similarities are striking; other times the differences stand as a reminder of future conflicts and misunderstandings. Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Handout 1 Discovering Diplomacy One of Lewis and Clark's missions was to open diplomatic relations between the United States and the Indian nations of the West. As Jefferson told Lewis, "it will now be proper you should inform those through whose country you will pass . . . that henceforth we become their fathers and friends." When Euro-Americans and Indians met, they used ancient diplomatic protocols that included formal language, ceremonial gifts, and displays of military power. But behind these symbols and rituals there were often very different ways of understanding power and authority. Such differences sometimes made communication across the cultural divide difficult and open to confusion and misunderstanding. An important organizing principle in Euro-American society was hierarchy. Both soldiers and civilians had complex gradations of rank to define who gave orders and who obeyed. While kinship was important in the Euro-American world, it was even more fundamental in tribal societies. Everyone's power and place depended on a complex network of real and symbolic relationships. When the two groups met--whether for trade or diplomacy--each tried to reshape the other in their own image. Lewis and Clark sought to impose their own notions of hierarchy on Indians by "making chiefs" with medals, printed certificates, and gifts. Native people tried to impose the obligations of kinship on the visitors by means of adoption ceremonies, shared names, and ritual gifts. Blunderbuss The Lewis and Clark expedition was in many ways an infantry company on the move, fully equipped with rifles of various kinds, muskets, and pistols. Among the firearms were two blunderbusses. Named after the Dutch words for "thunder gun," the blunderbuss was Blunderbuss, ca. 1809-1810 Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Behring Center, Washington, D.C. (53) unmistakable for its heavy stock, short barrel, and widemouthed muzzle. Other expedition guns might be graceful in design and craftsmanship but the stout blunderbuss simply signified brute force and power. Lewis and Clark fired their blunderbusses as signs of arrival when entering Indian camps or villages. Pipe tomahawk Pipe tomahawks are artifacts unique to North America-created by Europeans as trade objects but often exchanged as diplomatic gifts. They are powerful symbols of the choice Europeans and Indians faced whenever they met: one end was the pipe of peace, the other an axe of war. Lewis's expedition packing list notes that fifty pipe tomahawks were to be taken on the expedition. Pipe tomahawk (Shoshone), 1800s Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (39) Jefferson's Secret Message to Congress While Jefferson made no effort to hide the Lewis and Clark expedition from Spanish, French, and British officials, he did try to shield it from his political enemies. By the time he was ready to request funds for the enterprise, Jefferson's relationship with the opposition in Thomas Jefferson "Confidential" Message to Congress, January 18, 1803 Page 2 - Page 3 - Page 4 Transcript Manuscript Manuscript Division (56) Congress was anything but friendly. When the president suggested including expedition funding in his regular address to Congress, Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin (1761-1849) urged that the request be made in secret. The message purported to focus on the state of Indian trade and mentioned the proposed western expedition near the end of the document. Jefferson's Instructions for Meriwether Lewis No document proved more important for the exploration of the American West than the letter of instructions Jefferson prepared for Lewis. Jefferson's letter became the charter for federal exploration for the remainder of the nineteenth century. The letter combined national aspirations for territorial expansion with scientific discovery. Here Jefferson sketched out a comprehensive and flexible plan for western exploration. That plan created a military exploring party with one key mission-finding the water passage across the continent "for the purposes of commerce"--and many additional objectives, ranging from botany to ethnography. Each section of the document was really a question in search of a western answer. Two generations of American explorers marched the West in search of those answers. Thomas Jefferson to Meriwether Lewis, June 20, 1803 Page 2 - Page 3 - Page 4 Transcript Letter press copy of manuscript letter [instructions for the Corps of Discovery] Manuscript Division (57) Jefferson Peace Medal The American republic began to issue peace medals during the first Washington administration, continuing a tradition established by the European nations. Lewis and Clark brought at least eighty-nine medals in five sizes in order to designate five "ranks" of chief. In the eyes of Americans, Indians who accepted such medals were also acknowledging American sovereignty as "children" of a new "great father." And in a moment of imperial United States Mint Thomas Jefferson peace medal, 1801 Reverse side of medal Silver Courtesy of the Oklahoma State Museum of History, Oklahoma City (41) bravado, Lewis hung a peace medal around the neck of a Piegan Blackfeet warrior killed by the expedition in late July 1806. As Lewis later explained, he used a peace medal as a way to let the Blackfeet know "who we were." Making Chiefs Lewis was frustrated by the egalitarian nature of Indian society: "the authority of the Chief being nothing more than mere admonition . . . in fact every man is a chief." He set out to change that by "making chiefs." He passed out medals, certificates, and uniforms to give power to chosen men. By weakening traditional authority, he sought to make it easier for the United States to This image is not available online: Certificate of loyalty, ca. 1803 Printed document with wax seal and ribbon Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (43) negotiate with the tribes. Lewis told the Otos that they needed these certificates "In order that the commandant at St. Louis . . . may know . . . that you have opened your ears to your great father's voice." The certificate on display was left over from the expedition. Making Speeches In their speeches, Lewis and Clark called the Indians "children." To explorers, the term expressed the This image is not available online: Speech to the Yellowstone Indians, 1806 Speech of Arikara chiefs, 1804 Manuscripts Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (44, 49) relationship of ruler and subject. Clark modeled this speech to the Yellowstone Indians on one that Lewis gave to Missouri River tribes. In their speeches, the Indians called Lewis and Clark "father," as in this example made by the Arikira Chiefs. To them, it expressed kinship and their assumption that an adoptive father undertook an obligation to show generosity and loyalty to his new family. William Clark recorded this speech as it was made by the chiefs. Making Kinship In tribal society, kinship was like a legal system--people depended on relatives to protect them from crime, war, and misfortune. People with no kin were outside of society and its rules. To adopt Lewis and Clark into tribal society, the Plains Indians used a pipe ceremony. The ritual of smoking and sharing the pipe was at the heart of much Native American diplomacy. With the pipe the captains accepted sacred obligations to share wealth, aid in war, and revenge injustice. At the end of the ceremony, the pipe was presented to them so they would never forget their obligations. This pipe may have been given to Lewis and Clark. Pipe bowl [Plains/Great Lakes], ca. 1800-1850 Stone (catlinite) and lead Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Gift of the heirs of David Kimball, 1899 (48a) Pipe stem [Plains/Great Lakes], ca. 1800-1850 Wood, ivory-billed woodpecker head and scalp, wood duck face patch, dyed downy feathers, dyed horsehair, dyed artiodactyls hair, dyed and undyed porcupine quills, sinew, bast fiber cords, glazed cotton fabric, sinew, bast fiber cords, glazed cotton fabric, twill-woven wool tapes, silk ribbons, and shell beads (48b) Jefferson's Cipher While Jefferson knew that for much of the journey he and his travelers would be out of touch, the president thought Indians and fur traders might carry small messages back to him. A life-long fascination for gadgets and secret codes led Jefferson to present Lewis with this key-word cipher. Lewis was instructed to "communicate Jefferson's cipher for the Lewis and Clark expedition, 1803 with sample message "I am at the head of the Missouri. All well, and the Indians so far friendly." Manuscript document Manuscript Division (55) to us, at seasonable intervals, a copy of your journal, notes & observations, of every kind, putting into cipher whatever might do injury if betrayed." The scheme was never used but the sample message reveals much about Jefferson's expectations for the expedition. Gifts with a Message Gift-giving was an essential part of diplomacy. To Indians, gifts proved the giver's sincerity and honored the tribe. To Lewis and Clark, some gifts advertised the technological superiority and others encouraged the Indians to adopt an agrarian lifestyle. Like salesmen handing out free samples, Lewis and Clark packed bales of manufactured goods like these to open diplomatic relations with Indian tribes. These beads came from Mitutanka, the village nearest to Fort Mandan. Jefferson advised Lewis to give out corn mills to introduce the Indians to mechanized agriculture as part of his plan to "civilize and instruct" them. Clark believed the mills were "verry Thankfully recived," but by the next year the Mandan had demolished theirs to use the metal for weapons. Kettle, beads, and cornmill, late 1700s Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society (kettles), St. Paul; Ralph Thompson Collection of the North Dakota Lewis & Clark Bicentennial Foundation (beads), Washburn; and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (cornmill) (50, 51, 52) Displays of Power In situations when ceremonies, speeches, and gifts did not work, both the Corps and the Indians gave performances that displayed their military power. The American soldiers paraded, fired their weapons, and demonstrated innovative weaponry. The Indians used war clubs, like this Sioux club, in celebratory scalp dances. Three decades later, Swiss artist Karl Bodmer accompanying naturalist Prince Maximillian, retraced Lewis and Clark's trek on the Missouri River and vibrantly recorded a similar scene in the print displayed above. Karl Bodmer (1809-1893) "Scalp Dance of the Minatarres" [Hidatsa] from Reise in das innere Nord-America in den Jahren 1832 bis 1834. Koblenz: 1839-41 Hand-colored lithograph Rare Book and Special Collections Division (54C) War club (Sioux, Cheyenne River Reservation), pre-1870 Courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia (54) Jefferson's Speech to a Delegation of Indian Chiefs Indian delegations had long been part of European diplomacy with native people, and they came to play an increasingly important role in U.S. Indian policy as well. Even before leaving St. Louis, Lewis and Clark began organizing delegations to visit the new "great father" in Washington. Jefferson's speech to a group of chiefs from the lower Missouri River is an arresting combination of Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) Speech to a delegation of Indian chiefs, January 4, 1806 Page 2 - Page 3 - Page 4 friendship, promises of peaceful relations in a shared country, and thinly veiled threats if Indians rejected Transcript Manuscript Manuscript Division (45) American sovereignty. Reminding the chiefs of the changes in international diplomacy after the Louisiana Purchase, Jefferson insisted that "We are now your fathers; and you shall not lose by the change." But behind all the promises of a shared future was an unmistakable threat. As the president said, "My children, we are strong, we are numerous as the stars in the heavens, & we are all gunmen." Indian Speech to Jefferson A delegation of chiefs from western tribes was sent by Lewis to Washington, D.C. President Jefferson welcomed them with words of peace and friendship. But if President Jefferson expected his native visitors to quietly [Speech of the] "Osages, Missouri, Otos, Panis, Cansas, Ayowais, & Sioux Nations to the president of the U.S. & to the Secretary of War, January [4], 1806" Page 1 - Page 2 - Page 3 - Page 4 Page 5 - Page 6 - Page 7 - Page 8 Page 9 - Page 10 - Page 11 Page 12 - Page 13 - Page 14 Page 15 - Page 16 Transcript Manuscript document in the hand of the clerk, endorsed by 14 tribal representatives Courtesy of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Library, Philadelphia (46) accept their status as "children" in the new American order, he was mistaken. In their speech to Jefferson, the chiefs raised two important concerns: the troubled economic relations between native people and the federally operated trading posts and the rising tide of violence Indians suffered at the hands of white settlers on the Missouri River frontier. These chiefs were determined to speak the truth "to the ears of our fathers." In return, they expected that government officials would "open their ears to truth to get in." Handout 2 Geography In the exploration instructions prepared for Lewis, Jefferson directed that his explorers record "the face of the country." Geography, especially as recorded on maps, was an important part of the information collected by the Corps of Discovery. In planning the expedition, Lewis and Gallatin collected the latest maps and printed accounts portraying and describing the western country. This visual and printed data was incorporated into a composite document--the Nicholas King 1803 map-which the expedition carried with them at least as far as the Mandan villages. As Lewis and Clark traversed the country, they drew sketch maps and carefully recorded their astronomical and geographic observations. Equally important, they gathered vital knowledge about "the face of the country" from native people. During winters at Fort Mandan on the Missouri in 18041805 and at Fort Clatsop on the Pacific Coast in 1805-1806 the explorers added new details from their sketch maps and journals to base maps depicting the course of the expedition. The first printed map of the journey did not appear until 1814 when Nicholas Biddle's official account of the expedition was published in Philadelphia and London. Euro-American explorers were not the only ones to draw maps of the western country. As every visitor to Indian country soon learned, native people also made sophisticated and complex maps. Such maps often covered thousands of miles of terrain. At first glance Indian maps often appear quite different from those made by Euro-Americans. And there were important differences that reflected distinctive notions about time, space, and relationships between the natural and the supernatural worlds. William Clark was not the only expedition cartographer to struggle with those differences. But the similarities between Indian maps and Euro-American ones are also worth noting. Both kinds of maps told stories about important past events, current situations, and future ambitions. Both sorts of maps used symbols to represent key terrain features, major settlements, and sacred sites. Perhaps most important, Euro-Americans and Native Americans understood that mapping is a human activity shared by virtually every culture. Nicholas King's 1803 PreExpedition Map In March 1803, War Department cartographer Nicholas King compiled a map of North America west of the Mississippi in order to summarize all available topographic information about the region. Nicholas King, with annotations by Meriwether Lewis "Tracing of western North America showing the Mississippi, and the Missouri for a short distance above the Kansas, Lakes Michigan, Superior, and Winnipeg, and the country onwards to the Pacific" with annotations in the hand of Meriwether Lewis, 1803. [carried as far as Mandan village] Engraved map with annotations in pen and ink Geography and Map Division (64) Representing the federal government's first attempt to define the vast empire later purchased from Napoleon, King consulted numerous published and manuscript maps. The composite map reflects Jefferson and Gallatin's geographical concepts on the eve of the expedition. It is believed that Lewis and Clark carried this map on their journey at least as far as the MandanHidatsa villages on the Missouri River, where Lewis annotated in brown ink additional information obtained from fur traders. Source Map for the Bend of the Missouri River One of the sources for Nicholas King's 1803 map was this sketch of the Great Bend of the Missouri River (north of present-day Bismarck, North Dakota). Copied by Lewis from a survey for the British North West Company by David Thompson, this map provided the exact latitude and longitude of that important segment of the Missouri. Thompson, traveling overland in the dead of winter, spent three weeks at the Mandan and Pawnee villages on the Missouri River, calculating Meriwether Lewis after David Thompson (1770-1857) [Bend of the Missouri River] 1798 Manuscript map Geography and Map Division (64A) astronomical observations. He also recorded the number of houses, tents, and warriors of the six Indian villages in the area. Fort Mandan Map Throughout the winter of 18041805 at Fort Mandan, William Clark drafted a large map of the West --what he called "a Connection of the country." That map, recopied several times by Nicholas King, provided the first accurate depiction of the Missouri River to Fort Nicholas King (1771-1812) after William Clark "A Map of Part of the Continent of North America : Between the 35th and 51st Degrees of North Latitude, and Extending from 89 Degrees of West Longitude to the Pacific Ocean." Washington, 1805 Manuscript map Geography and Map Division (62) Mandan based on the expedition's astronomical and geographical observations. Drawing on "information of Traders, Indians, & my own observation and idea," Clark sketched out a conjectural West--one characterized by a narrow chain of mountains and rivers with headwaters close one to the other, still suggesting an easy water passage to the Pacific Coast. Indian Map of Columbia and Snake Rivers Although there are journal notes stating that Indians provided geographical information for Lewis and Clark and drew maps on animal skins or made rough sketches in the soil, no original examples survive. However, there are several collaborative efforts in which members of the Corps redrew Indian sketches often combining their own observations with Indian information. This sketch map found in one of William Clark's field notebooks is a good example of a map derived from Indian information. It is a diagram of the relative location of tributaries of the Columbia and Snake (Lewis) rivers in present-day eastern Washington and Oregon. William Clark. [Drawing of Northwest Coast canoe with carved figures at each end,] February 1, 1806. Transcript Copyprint of journal entry Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St Louis (68) [William Clark] "This Sketch was given to me by a Shaddot, a Chopunnish & a Shillute at the Falls of Columbia, 18 April 1806" Manuscript map in field notebook Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (59) Field Maps of the Fort Clatsop Area This pair of maps is from a collection of manuscript field maps drafted by Clark as the Corps descended the Columbia River and wintered on the Pacific Coast at Fort Clatsop. On the left, William Clark [Draft of the Columbia River, Point Adams, and South Along the Coast] and [Map from a "Clott Sopp Indn."], 1806 Copyprint of manuscript maps Courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven (59A) Clark drew a rough sketch of the mouth of the Columbia River, oriented with south at the top of the sheet. The other is one of the cruder examples of a map derived from Indian information, with Clark noting "This was given by a Clott Sopp Indn." It shows a small portion of the Pacific Coast and locates several tribes and villages. Sitting Rabbit's Map of the Missouri River Displayed here is a portion of a 1906-1907 map depicting the Missouri River through North Dakota to the mouth of the Yellowstone River. It was prepared by Sitting Rabbit, a Mandan Indian, at the request of an official of the State Historical Society of North Dakota. Although it uses a Missouri River Commission map as its base, the content provides a traditional Indian perspective of the river's geography, especially noting former Mandan village sites with earthen lodges. The portion of the river shown here corresponds to the same Sitting Rabbit (I Ki Ha Wa He, also known as Little Owl) [Map of Missouri River from South Dakota-North Dakota boundary to mouth of Yellowstone River], 1906-1907 Copyprint of painting on canvas Courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismark (59C) stretch of river delineated on Clark's route map (below). Missouri Route Map near Fort Mandan Throughout the expedition, William Clark prepared a series of This image is not available online: [Route Map about October 16-19, 1804], copy of original map made in 1833 Copyprint of manuscript copy Courtesy of the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha (59D) large-scale route maps, with each sheet documenting several days' travel. On these sheets he recorded the course of rivers navigated, mouths of tributary streams, encampments, celestial observations, and other notable features. Big River on Sitting Rabbit's map (above) is identified as Cannon Ball River on Clark's map and Beaver Creek is recorded as Warraconne River or "Plain where Elk shed their horns," by Clark. Fort Clatsop Map This post-expeditionary map prepared by Washington, D.C., cartographer Nicholas King, probably in 1806 or 1807, most likely incorporates information from a map prepared by Lewis and Clark in February 1806 at Fort Clatsop on the Oregon coast. Although the original map no longer exists, such a map is mentioned in the expedition's journals. Using King's 1805 base map, which records information observed as far as Fort Mandan, this present copy adds geographical observations from Fort Mandan to the west coast, as well as data from the return trip. Nicholas King after Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. "Map of Part of the Continent of North America . . . as Corrected by the Celestial Observations of Messrs. Lewis and Clark during their Tour of Discoveries in 1805." Washington, D.C., 1806? Copyprint of manuscript map Courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum, Boston (70) Clark's Map of Midwestern Indian Settlements Following his appointment as governor of the Missouri Territory in 1813, William Clark sketched this map of various Indian tribes and villages throughout the Missouri and Illinois territories, showing the locations of numerous forts and settlements. He prepared it in response to British incursions on the frontier during the War of 1812, when it was feared that the Indians, many of them allied with the British, would attack white settlements. The map also reflects Clark's continuing post-expedition interest in Indian activities having been appointed superintendent of Indian affairs at St. Louis in 1807. William Clark (1770-1838) "Plan of the N.W. Frontier from Governor Clarke," [St. Louis], ca. 1813 Manuscript map Geography and Map Division (67A) William Clark's compass on chain Brass, jasper, glass, paint William Clark's magnet, ca. 1802 Iron, paint Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (65, 66) Frazer's PostExpedition Map Private Robert Frazer was the first member of the Lewis and Clark party to announce publication of an expedition journal. His account never reached print, and the original journal was lost. This manuscript map is the only remnant of that initial publishing attempt. Since Frazer had little or no knowledge of surveying or natural sciences, the map is a strange piece of cartography. He traces the expedition's route, but continues to depict older views of the Rocky Mountains and western rivers. Sometimes ignored, the Frazer map was one of the first to reveal the course of the journey and some of its geographic findings. Robert Frazer (d. 1837) "A Map of the Discoveries of Capt. Lewis & Clark from the Rockey Mountain and the River Lewis to the Cap of Disappointment or the Columbia River at the North Pacific Ocean," 1807 Manuscript map Geography and Map Division (69) First Published Map of Expedition's Track This was the first published map to display reasonably accurate geographic information of the trans-Mississippi West. Based on a large map kept by William Clark, the engraved copy accompanied Nicholas Biddle's History of the Expedition (1814). As the landmark William Clark "A Map of Lewis and Clarks Track" from History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the Sources of the Missouri, thence Across the Rocky Mountains and Down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean, 1814 Samuel Lewis, copyist; Samuel Harrison, engraver Engraved map Geography and Map Division (67) cartographic contribution of the expedition, this "track map" held on to old illusions while proclaiming new geographic discoveries. Clark presented a West far more topographically diverse and complex than Jefferson ever imagined. From experience, Clark had learned that the Rockies were a tangle of mountain ranges and that western rivers were not the navigable highways so central to Jefferson's geography of hope. History of the Expedition After Lewis's death in September 1809, Clark engaged Nicholas Biddle to edit the expedition papers. Using the captains' original journals and those of Sergeants Gass and Ordway, Biddle completed a narrative by July 1811. After delays with the publisher, a two-volume edition of the Corps of Discovery's travels across the continent was finally available to the public in 1814. More than twenty editions appeared during the nineteenth century, including German, Dutch, and several British editions. [Nicholas Biddle and Paul Allen, eds.] History of the Expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the Sources of the Missouri, then across the Rocky Mountains and down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean. Performed during the years 1804-5-6. By order of the Government of the United States. Page 2 Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep; New York: Abm. H. Inskeep. J. Maxwell, Printer, 1814 Rare Book and Special Collections Division (67B) Calculating Distance In order to make astronomical observations that would aid in calculating distances, the Corps took a sextant on their journey. On July 22, 1804, while the expedition was above the mouth of the Platte River in eastern Nebraska, Lewis gave a detailed description of the operation of the sextant and other tools that reveals his struggle to use the complicated instruments. A select number of books were taken on the expedition including British astronomer Nevil Maskelyne's Tables Requisite to be Used with the Nautical Ephemeris for Finding the Latitude and Longitude at Sea. W. & S. Jones Holburn, London [patented 1788] Sextant Brass, wood, silver Courtesy of the National Museum of American History, Behring Center (60) Nevil Maskelyne (1732-1811). Tables Requisite to be Used with the Nautical Ephemeris for Finding the Latitude and Longitude at Sea. Page 2 London: William Richardson, 1781 Rare Book and Special Collections Division (61) Handout 3 Animals Jefferson subscribed to the eighteenth-century Enlightenment notion that assembling a complete catalog of the Earth's flora and fauna was possible. In his instructions, he told Lewis to observe "the animals of the country generally, & especially those not known in the U.S." The Corps of Discovery was the first expedition to scientifically describe a long list of species. Their journals, especially those kept by Lewis, are filled with direct observations of the specimens they encountered on the journey. Through objective measurements and anatomical descriptions, they defined various species previously unknown to Euro-Americans. Indians studied animal behaviors to understand moral lessons. Animals were beings addressed respectfully as "grandfather" or "brother." Because animals intersected the worlds of the sacred and the profane, Indians regarded them as intermediaries between the human and spiritual realms. Lewis's woodpecker The woodpecker displayed above may be the only specimen collected during the Lewis and Clark expedition to survive intact. Lewis first saw the bird on July 20, 1805, but did not get a specimen until the following spring at Camp Chopunnish on the Clearwater River in Idaho. Lewis's description of the bird's belly is still Specimen of a "Lewis woodpecker" [Asyndesmus lewis, collected Camp Chopunnish, Idaho, 1806] Preserved skin and feathers Courtesy of Harvard University Museum of Comparative Zoology, Boston (71) accurate when examining the specimen today: "a curious mixture of white and blood red which has much the appearance of having been artificially painted or stained of that colour." Observing "the animals of the country generally" Lewis covered pages with descriptions of animals and plants during the winter of 1805-1806. This particular journal kept during that period contains abundant zoological notes in Lewis's hand. The journal is open to a description of the Corps first encounter with a white-tailed jack rabbi--an animal considered so impressive that both Lewis and Clark wrote extensive descriptions of it. On selected occasions both captains illustrated their notes. In the reproduction above Clark sketched the now-endangered condor. Lewis had correctly observed in his journal: "I bleive this to be the largest bird of North America." Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) "Shield killed a hare of the prarie . . ." Journey entry, September 14, 1804 Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia (40) William Clark (1770-1838) Head of a Vulture (California condor), February 17, 1806 Copyprint of journal illustration Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St Louis (74A) Representing Beings The Indian sense of "personhood" extends far beyond the western conception of human beings. In Indian culture animal people, plant people, sky peopleCall are beings in their own right. Indian art portrays a being's inner essence, not its physical form. The Columbia River artist who created this twined circular basket decorated it with images of condors, sturgeons, people, and deer -- abstractions that are given equal importance in the woven pattern. This nineteenth-century Sioux clay and wood pipe portrays a buffalo, whose spirit, or Tananka, cares for children, hunters, and growing things. It may have be created as a presentation pipe. Sally bag with condors (Wasco), pre-1898 Twine, corn husk Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society, Portland (75) Buffalo effigy pipe (Sioux), pre-1872 Catlinite, wood Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (76) Hunting Bear Patrick Gass was one of the three sergeants in the Corps of Discovery. His account, first printed in 1807, was the only one available to curious readers until the official publication appeared in1814. This Gass edition contains six woodcuts, two of which depict encounters with bears. The image above may have been based on Corps member Hugh McNeal's experience on July 15, 1806. Lewis records: ". . .and with his clubbed musquet he struck the bear over the head and cut him with the guard of the gun and broke off the breech, the bear stunned with the stroke fell to his ground. . .this gave McNeal time to climb a willow tree." Patrick Gass. "Bear Pursuing his Assailant" in A Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery . . . Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1810 Wood engraving Rare Book and Special Collections Division (72A) Patrick Gass. "Captain Clark and his men shooting bears," in A Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery . . . Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1810 Copyprint of wood engraving Rare Book and Special Collections Division(72B) The Power of the Bear Artist George Catlin painted the scene of a dance held in preparation for a traditional Sioux bear hunt in 1832. These dances were performed in order to communicate with "the Bear Spirit." According to Catlin, the Sioux believe this spirit "holds somewhere an invisible existence that must be consulted and conciliated." This clay Sioux pipe bowl probably depicts the bear's role as teacher and transmitter of power. George Catlin (1796B1872) Bear Dance of the Sioux, 1832 [printed 1844] Hand-colored lithograph Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (74) Bear effigy pipe bowl (Sioux, Osage or Pawnee), pre-1830s Catlinite Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (72) Handout 4 Dressed in Courage In both Euro-American and native cultures, clothing communicated messages about the wearer's biography, rank, and role in society. In both cultures, a warrior's clothing was his identity and men entered battle dressed in regalia that displayed their deeds and status. Symbolic insignia revealed a complex code about who a man was and what he had accomplished. But differences did exist. For instance, Plains Indian men wore clothing that incorporated symbols of their spirit visions, tribal identity, and past deeds as manifestations of the spiritual powers that helped them in battle. European soldiers wore similar symbols but as a way to display and inspire uniform loyalty to their nation. Wearing Achievement The U.S. Army lavished effort on the details of uniforms, increasing the psychological impact on the wearer and his opponent. Military insignia were designed to prevent any ambiguity about chains of command, so that a soldier could instantly tell whom to obey. The U.S. Army was so small in 1804 that no complete uniforms survive. This reproduction portrays a captain in the full-dress uniform of the 1st U.S. Infantry Regiment, to which Lewis belonged. The "Kentucky" rifle shown below--a .45 caliber flint lock--was passed down through William Clark's family. Infantry captain's uniform, bicorne hat [not shown] Reproduction by Timothy Pickles, 2003 Textile Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (79) Rifle, post 1809, lock by Rogers & Brothers, Philadelphia Steel barrel, iron fittings, German silver plates, tiger maple stock Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (73) The Plains Warrior A Plains Indian warrior relied on personal power in battle, and his dress incorporated symbols of his spirit visions, his tribal identity, and his past deeds. The leader of a war party often wore a painted shirt that detailed his war record. On such shirts made from animal skins, the contours of the pelt were left intact in the belief that the animal would lend its qualities to the wearer. The most powerful shirts were fringed with locks of human hair provided by relatives and supporters to represent War shirt, 1843 Antelope skin, quill work Courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery (80) the man's responsibilities to his relations. This shirt, probably Blackfeet, has buffalo-track symbols on the neck flap that evoke the power of the bison to aid the warrior in battle. Images of Heroism Plains Indian men wore painted skin robes that told of their achievements. This image of Shoshone Chief Washakie's war robe shows a series of diagrammatic battle scenes. Here, events happen not in a landscape but in a symbolic realm of deeds. Depictions of his enemies are not individualized, but are instead given costumes, hairstyles, or equipment that represent tribal affiliation, society membership, and past deeds. Warriors are sometimes represented by disembodied guns or Washakie war robe (Shoshone), pre-1897 Paint on deer hide Copyprint of artifact Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, D.C. (81) arrows. The Ideal Military Hero In 1759, at the height of the French and Indian War, General Wolfe led a British-American assault on the French outside Quebec. The print, based on a painting by Benjamin West, shows the wounded general dying just as a messenger brings news that the enemy is retreating. In the moment of both victory and death, William Woollett, after a painting by Benjamin West The Death of General Wolfe. London: Woollett, Boydell & Ryland, 1776 Engraving Prints and Photographs Division (81B) Wolfe achieves transcendent glory. His uplifted eyes suggest both sacrifice for the nation and triumph over death--not through faith but through fame. This was an idealized image to which military men of Lewis and Clark's generation aspired. Coyote Headdress Coyote, the mythic trickster of the Plains Indians, was the protector of the scouts who spied on the enemy for a war party. This nineteenth-century Teton headdress from the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota was meant to summon and symbolize Coyote's craftiness. Coyote headdress (Teton Sioux), nineteenth century Pelt, feathers, canvas, wool, hawk bell Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, D.C. (78) Spontoon and Gorget The spontoon, a long wooden shaft with a spear at one end, became popular with the American army during the Revolutionary War. Although it was required equipment that signified an officer's rank, these pikes were commonly abandoned for more practical weapons in battle. Lewis used his as a walking stick, a grizzly-bear spear, and a gun rest, but never to rally troops in battle. The origins of the gorget can be traced to the chivalric armor. American army officers wore these ceremonial insignia high on the chest. Lewis presented gorgets (which he called "moons") to Indian leaders to symbolize rank. Spontoon (American/Fort Ticonderoga), late eighteenth century Iron, wood Courtesy of the Collection of Fort Ticonderoga Museum, New York (81A) Richard Rugg Gorget, London, ca. 1783 Silver Courtesy of William H. Guthman Collection (47) Bear Claw Necklace To wear a bear claw necklace was a mark of distinction for a warrior or a chief, and the right to wear it had to be earned. These powerful symbols were a part of the culture of the Great Lakes, Plains, and Plateau tribes. On August 21, 1805, Lewis wrote in this journal that Shoshone "warriors or such as esteem themselves brave men wear collars made of the claws of the brown bear. . . . These claws are ornamented with beads about the thick end near which they are pierced through their sides and strung on a throng of dressed leather and tyed about the neck . . . . It is esteemed by them an act of equal celebrity the killing one of these bear or an enimy." Animal claw necklace (Teton Sioux), mid-nineteenth century Bear claws, hide Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, D.C. (82) Handout 5 Plants In his instructions to Lewis, Jefferson directed the party to observe and record "the soil & face of the country, it's growth & vegetable productions, especially those not of the U.S. . . . the dates at which particular plants put forth or lose their flower, or leaf . . . ." The study and collection of plants was one of Jefferson's life-long pursuits. When he instructed the Corps in their approach to cataloging the country's flora, Jefferson again set the pattern for subsequent explorations. Jefferson, however, was not purely motivated by science; plants thought to have medicinal properties, like tobacco and sassafras, were important to the U.S. economy. As the Napoleonic Wars swept Europe and affected exports to the United States, there was a call to reduce America's dependence on foreign medicine and find substitutes on native soil. Indians and Europeans had been exchanging knowledge about curing and health for three centuries, yet they still held very different beliefs. Indian doctors focused on the patient's relationship to the animate world around him. Euro-American doctors saw the body as a mechanical system needing regulation. Meriwether Lewis, instructed by America's foremost physician Dr. Benjamin Rush, University of Pennsylvania botanist Benjamin Barton, and his own mother, a skilled herbalist, was to serve as the Corps doctor, but William Clark also became adept in treating various illnesses. Though Clark rejected Indian explanations, he often turned to Indian techniques when members of his own party became ill. Curing the Corps Lewis and Clark were not persuaded by Indian explanations of why illness occurred but often used Indian cures in preference to their own. The Corps began its journey stocked with traditional western medicinal treatments and tools. Lewis used lancets to let out blood in such dangerous conditions as heat exhaustion and pelvic inflammation, and tourniquets to stop blood flow. Tourniquet, early nineteenth century Brass, leather, iron Lancet, early nineteenth century Tortoise shell, steel Clyster syringe, late eighteenth century Pewter, wood Courtesy of the Mütter Museum, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia (86, 87, 88) Bleeding was thought to relieve congestion in internal organs. Lewis originally thought he would need three syringes for enemas but settled for one. There is no further mention of its use. Laxatives, derived from plant sources, were also used to purge the body of impurities. Rules of Health Thomas Jefferson asked Benjamin Rush, a noted physician and professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, to "prepare some notes of such particulars as may occur in his journey & which you think should draw his attention & enquiry." Dr. Rush restricted his advice to practical hints for maintaining health in the field--some of it unwelcome like using alcohol for Benjamin Rush (ca.1745-1813) to Meriwether Lewis (17741809), June 11, 1803 cleaning feet instead of for drinking. Many Americans did not trust professional medicine and instead used folk cures like these written down by Clark after the expedition. Many folk cures originally came from Indian sources. "Rules for Preserving his Health" Manuscript Manuscript Division (91) This image is not available online: William Clark Cures for toothache and "whooping cough," early nineteenth century Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (92) Summoning the Spirits An Indian doctor's job was to identify the being that had caused an illness, then overcome or placate it. An Indian patient lived in an animate world, surrounded by entities who could make him ill. Medicinal herbs and roots were powdered and mixed in a mortar like this one from the Northern Plains. Drums and herbs were used to summon helpful spirits as aids in healing. Fragrant herbs pleased and attracted good influences and drove away evil ones. This sweetgrass braid was used as an incense to purify implements, weapons, dwellings, and people. Mortar and pestle (Plateau), prehistoric Stone Courtesy of the Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington (89a,b) Sweetgrass braid (Lakota), 1953 Sweetgrass, string Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (93) Drum (Northern Plains), nineteenth century Wood, hide Courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis (94) A Botanical Specimen While admitting that Lewis was "no regular botanist," Jefferson did praise "his talent for observation." And on June 11, 1806, during an extended stay with the Nez Perce people, Lewis showed that talent. Camas, sometimes known as quamash, was an important food plant for the Nez Perces. Lewis carefully described the plant's natural environment, its physical structure, the ways women harvested and prepared camas, and its role in the Indian diet. Some days later Lewis gathered samples of camas for his growing collection of western plants. Camassia quamash (Pursh), ["Collected by Lewis at Weippe Prairie, in present-day Idaho, June 23, 1806."] Herbarium sheet Courtesy of Academy of Natural Sciences, Ewell Sale Stewart Library, Philadelphia (84) Flora Americae Septentrionalis Frederick Pursh, an emigrant from Saxony who worked with botanist Benjamin Smith Barton in Philadelphia, published the first botanical record of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Pursh received a collection of dried plants from Lewis, which he classified and incorporated into his Flora Americae Septentrionalis. The volume is open to Clarkia pulchella, a member of the evening primrose family, which Pursh named in honor of William Clark. Pursh took some of the Lewis and Clark specimens to London to finish the book, including the silky lupine specimen to the far left. Frederick Pursh (1774-1820). Clarkia pulchella in Flora Americae Septentrionalis: or a Systematic Arrangement and Description of the Plants of North America. 2 vols. London: White, Cochrane, and Col., 1814 Rare Book and Special Collections Division (85) Lupinus sericens, Pursh, [silky lupine] [collected by Lewis at Camp Chopunnish, on the Clearwater River, Idaho, June 5, 1806] Herbarium sheet Courtesy of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, England (83) Root Digging Bag Among the Nez Perce, only women harvested plant foods. A man doing so risked derision and contempt. A Nez Perce woman's year was structured around plants. As each new food plant matured, its arrival was welcomed in a first fruits feast. Root bags were used in gathering, cooking, and for storage. An industrious woman could dig eighty or ninety pounds of roots in a day. Root digging bag (Plateau), pre-1898 Wild hemp and bear grass or rye grass, with dyes of alder, Oregon grape root, wolf moss, algae, and larkspur Courtesy of the Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington (95) A Gathering Basket The cedar bark basket was used across the Plateau for gathering berries, nuts, and roots. Bark baskets could be made easily when a person came across some forest food by stripping off a piece of cedar bark and folding it. Basket (Plateau), pre-1940 Cedar bark Courtesy of the Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington (97) A Sally Bag Plateau tribes gathered wild hemp and beargrass, then traded it to the Wishram and Wasco Indians at The Dalles in Oregon, the dividing line between North Coast and Plateau Indians. The traded raw materials would then be made into finished products like this sally bag, used for packaging food. Sally bag, pre-1898 Corn husk, dogbane [wild hemp] Courtesy of the Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington (96) Storing Roots Among the Shoshone, Lewis noted that dried roots were stored by being "foalded in as many parchment hides of buffaloe." Hide bags, like the one on display, were made by cleaning and sizing rawhide so that it had a smooth, Parfleche bag (Sahaptin), early nineteenth century Hide, pigment Courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Washington, D.C. (90) paintable surface. This bag is decorated in a distinctive Plateau style. Photo Analysis Worksheet Step 1. Observation Study the photograph for 2 minutes. Form an overall impression of the photograph and then examine individual items. Next, divide the photo into quadrants and study each section to see what new details become visible. Use the chart below to list people, objects, and activities in the photograph. Activities People Objects Step 2. Inference Based on what you have observed above, list three things you might infer from this photograph 1. 2. 3. Step 3. Questions What questions does this photograph raise in your mind? Where could you find answers to them? Map Analysis Worksheet TYPE OF MAP (Check one): Raised Relief Map Bird’s-eye Map Topographic Map Artifact Map Political Map Satellite photographic/mosaic Contour-line Map Pictograph Natural Resource Map Weather Map Military Map Other UNIQUE PHYSICAL QUALITIES OF THE MAP (Check one or more): Compass Name of mapmaker Handwritten Title Date Legend (key) Notations Other Scale DATE OF MAP: CREATOR OF THE MAP: WHERE WAS THE MAP PRODUCED? MAP INFORMATION List three things in this map that you think are important. 1. 2. 3. Why do you think this map was drawn? What evidence in the map suggests why it was drawn? Does the information in this map support or contradict information that you have read about this event? Explain. Write a question to the mapmaker that is left unanswered by this map. Written Document Analysis Worksheet TYPE OF DOCUMENT (Check one): Newspaper Map Advertisement Congressional Record Letter Telegram Patent Press Release Census Report Memorandum Report Other UNIQUE PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DOCUMENT (Check one or more): Interesting Letterhead Notations Handwritten “Received” stamp Typed Seals Other DATE(S) OF DOCUMENT: AUTHOR (OR CREATOR) OF THE DOCUMENT: POSITION (TITLE): FOR WHAT AUDIENCE WAS THE DOCUMENT WRITTEN? DOCUMENT INFORMATION (There are many possible ways to answer A-E.) A. List three things the author said that you think are important: B. Why do you think this document was written? C. What evidence in the document helps you know why it was written? Quote from the document. D. List two things the document tells you about life in the United States at the time it was written. E. Write a question to the author that is left unanswered by the document: