What is information competency?

advertisement

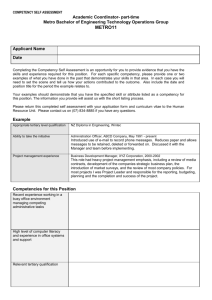

Information Competency as Graduation Requirement Information Competency Task Force Report Table of contents: What is information competency? ................................................................................ 2 Why are we considering an information competency graduation requirement? ........... 2 ACRL Standards and Recommendations ................................................................ 2 California Community Colleges ................................................................................ 3 Accreditation Standards ........................................................................................... 4 Success in Today’s Workplace ................................................................................ 5 Our Students ............................................................................................................ 5 Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 7 Options for Implementation .......................................................................................... 8 Model 1 – LIBR 318 As a Stand-Alone Class ........................................................... 8 Model 2 -- LIBR 318 Paired Up With Other Classes ................................................ 9 Model 3 – Info Comp Infused in a GE course ........................................................ 10 Model 4 – Info Comp Infused in a GE course – with Auxilary Modules .................. 10 Model 5 -- Self-paced online tutorial....................................................................... 11 Assessment ........................................................................................................... 11 Page 1 “The beginning of the 21st century has been called the Information Age because of the explosion of information output and information sources. It has become increasingly clear that students cannot learn everything they need to know in their field of study in a few years of college. Information literacy equips them with the critical skills necessary to become independent lifelong learners.” 1 Questions addressed in this report: What is information competency? Why are we considering an information competency graduation requirement? What are the recommendations? What are the implementation options and their challenges? What is information competency? According to Information Competency in the California Community Colleges, a paper adopted by the Academic Senate of California Community Colleges, the Academic Senate has identified the following key components and skills which comprise information competency for California community college students: State a research question, problem, or issue; Determine information requirements in various disciplines for the research questions, problems, or issues; Use information technology tools to locate and retrieve relevant information Organize information; Analyze and evaluate information; Communicate using a variety of information technologies; Understand the ethical and legal issues surrounding information and information technology; and Apply the skills gained in information competency to enable lifelong learning. Why are we considering an information competency graduation requirement? ACRL Standards and Recommendations “Introduction to Information Literacy”, http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlissues/acrlinfolit/infolitoverview/introtoinfolit/introinfolit.htm . American Library 1 Association, accessed Nov. 23, 2004. Page 2 In as early as January 1989, the American Library Association Presidential Committee on Information Literacy issued a report that stated, “Ultimately, information literate people are those who have learned how to learn. They know how to learn because they know how knowledge is organized, how to find information, and how to use information in such a way that others can learn from them. They are people prepared for lifelong learning, because they can always find the information needed for any task or decision at hand.” In January 2000, the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) issued Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education. The Standards provide a definition of information literacy/competency and outline five standards for information competency including performance indicators and learning outcomes.2 The Standards have served as a guideline for colleges across the nation to develop and implement instructional programs to provide information literacy/competency education to the students. California Community Colleges In 2001, the Academic Senate of California Community Colleges passed a resolution that recommended to the Board Of Governors that Information Competency become a locally designated graduation requirement for degree and Chancellor’s Office-approved certificate programs for California community colleges. Although the Department of Finance has intervened and thus forestalled the graduation requirement for information competency at this time, the Academic Senate recently reaffirmed their belief that Information Competency is still considered to be of primary importance to student success and that colleges should proceed with implementation whether or not the State mandates it. Its 2001 Resolution 9.01 S01 reads: Resolved, That the Academic Senate support the concept that each college be empowered to use its local curriculum processes to determine how to implement the information competency requirement, including the possibilities of developing stand-alone course, co-requisites, infusion in selected courses with or without additional units, and/or infusion in all general education course with or without additional units; … The following is a list of California community colleges that already have information competency graduation requirements or will have it in the near future: Cabrillo College Cerro Coso College Cuyamaca College Diablo Valley College Details of the Standards are available at ACRL’s web site at http://www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.htm. 2 Page 3 Merced College Santa Rosa Jr. College College of the Siskiyous Taft College Antelope (Fall 2005) City College of San Francisco (Fall 2006) College of the Sequoias (Fall 2005) Contra Costa (Fall 2006) Mission College (Spring 2006) Monterey Peninsula College (Fall 2005 or 2006) West Valley College (Fall 2005) 3 Accreditation Standards In the Accreditation Standards (http://www.accjc.org/documents/ACCJC NEW STANDARDS.pdf ) by the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges (ACCJC), Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC), information competency is identified as one of the learning outcomes expected from general education in community colleges. Standard II – Student Learning Programs and Services, A. Instructional Programs -- 3.b. reads: … General education has comprehensive learning outcomes for the students who complete it, including the following: A capability to be a productive individual and life long learner: skills include oral and written communication, information competency, computer literacy, scientific and quantitative reasoning, critical analysis/logical thinking and the ability to acquire knowledge through a variety of means. Standard II, section C. 1. b on library and learning support services reads: …The institution provides ongoing instruction for users of library and other learning support services so that students are able to develop skills in information competency. In line with the ACCJC Accreditation Standards, the SCC 2003 Report of the Institutional Self-Study for Reaffirmation of Accreditation has included in its planning agenda the establishment of information competency as a graduate requirement. On page 67, Standard Four: Educational Programs, D Curriculum and Instruction, Planning Agenda reads: Smalley, Topsy. “Information Competency.” http://www.topsy.org/infocomp.html. Accessed on December 9, 2004. 3 Page 4 To ensure the quality of instruction, academic rigor, and consistency of awarded credit: Beginning in 2003, the Curriculum Committee will work with faculty to evaluate the establishment of an information competency graduation requirement and/or courses, identify and re-evaluate general education courses in oral communication and critical thinking, and review all courses to ascertain consistency in the application of criteria for credit hours and distance education courses. Success in Today’s Workplace The Secretary's Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills (SCANS) formed by the U.S. Departments of Labor and Education studied the kinds of competencies and skills that workers must have to succeed in today's workplace. The results of the study were published in an article entitled What Work Requires of Schools: A SCANS Report for America 2000. In this document, information competency is identified as one of the five necessary skills to be successful in today’s workforce: Resources—allocating time, money, materials, space, and staff Interpersonal Skills—working on teams, teaching others, serving customers, leading, negotiating, and working well with people from culturally diverse backgrounds Information—acquiring and evaluating data, organizing and maintaining files, interpreting and communicating, and using computers to process information Systems—understanding social, organizational, and technological systems; monitoring and correcting performance; and designing or improving systems Technology—selecting equipment and tools, applying technology to specific tasks, and maintaining and troubleshooting technologies 4 Our Students The proliferation of new information resources, various interfaces of online databases and the ever-expanding WWW have left most of our students at a loss when it comes to doing research. Where do I start? What resources are available to me? Which one to choose? What keywords to use for my research? How do I distinguish between scholarly and popular materials? Is the resource reliable, accurate and appropriate for my research? What is plagiarism and how can I avoid it? How do I cite different resources in my paper? When and where can I find assistance? Etc. Etc. Etc. Most of our students cannot provide good answers to these questions without information competency trainings from the librarians. Sadly, more often than not, a student who The Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills, US Department of Labor. What required of schools: A SCAN Report for America. http://wdr.doleta.gov/SCANS/whatwork/whatwork.pdf. Accessed Dec 14. 4 Page 5 lacks training in information competency will equate quick and easy access to the quality of information. Hence, Google and Yahoo become the solution to all their research needs. Terri Clark from CRC is conducting research on the current information competency levels of the LRCCD students. She has provided an abbreviated and modified version of the Bay Area Information Competency Proficiency test to our students at ARC, CRC and SCC campuses. The results of her study will be available in Spring 2005. We are expecting the results to provide specific data on the information competency level of our students. Page 6 Recommendations The SCC Information Competency Task Force has engaged in discussions on the issues related to an information competency graduation requirement since Fall 2003. The group has examined such issues as: current students’ level of information skills; transferability to UC/CSU; information competency requirements already in place at UC/CSU; faculty and staff training on information competency; possible impact of information competency graduation requirements on students; different implementation models and their pros and cons; research data from other 4-year and 2-year colleges; and current efforts of teaching information competency at SCC. The Task Force agreed that a graduation requirement for information competency for degree programs would accomplish the following: enable us to reach more SCC students who lack adequate information competency skills; prepare them for their academic success at UC/CSU; provide them with the necessary skills to succeed in today’s workplace; and equip them with the crucial information skills for lifelong learning. However, we recognize that there are many more obstacles to overcome involving other campus constituencies, as well as obstacles involved in transferability, before this can become a reality. Therefore, the Task Force recommends that we move forward and explore the feasibility of different implementation methods by piloting selected models, thus preparing ourselves for the full-scale implementation of an information competency graduation requirement in the future. The librarians would continue current practices in information competency instruction during the implementation phase. The following is an outline of the possible implementation methods that are either currently in practice or in consideration. Projection of the numbers of students and classes is included for the purpose of clarifying our ideas as well as future planning. These models are most likely to be adopted concurrently as complementary parts of the whole SCC information competency instructional program. Page 7 Options for Implementation Model 1 – LIBR 318 As a Stand-Alone Class LIBR 318 (Library Research and Information Literacy) - Online or classroom - 1 unit credit - 9 weeks - Transferable to UC/CSU LIBR 318 is a course designed to teach a full range of information competency skills to community college students. According to its curriculum, students upon completion of the course will be able to: Select, analyze, and develop a research topic. Plan a research strategy. Choose relevant books and periodical articles. Apply database and Internet search techniques. Organize and analyze information. Evaluate and cite information sources. Recognize ethical and legal issues regarding copyright. According to the data from the SCC research office, SCC has an average of about 800 students to graduate with degrees each year. If we assume 800 graduates each year and a class size of 30 students, we will need to teach 27 sessions each year. Here is how we might spread the load out among the Fall, Spring and Summer semesters: 12 sessions in Fall -- 6 sessions in the first nine weeks and 6 in the second nine weeks 12 sessions in Spring -- 6 session in the first nine weeks, 6 in the second nine week 3 sessions in Summer An addition of 27 classes each semester will add a significant amount of workload to the full time librarians who are already overloaded with providing library instructional trainings and research assistance to our students. Challenges: Finding enough librarian instructors to cover the 27 classes. Unless we run almost all sessions entirely online, we will need accommodations for classroom space. SCC library has 2 classrooms in the Page 8 LR building, which are heavily used by regular library orientation classes and Library Information Technology classes. If all the librarians are to teach LIBR 318 online, there is a need for Blackboard training for some librarians. Model 2 -- LIBR 318 Paired Up With Other Classes LIBR 318 is offered in combination with a class in another discipline. Each class still maintains its original course goals and structure of instruction. The content in LIBR 318 will be customized to support the goals and objectives of the subject discipline course. LIBR 318 has been offered as a part of a Learning Community since 2003. Besides LIBR 318, classes involved included English 1A, English Writing 300 and Psychology 300. Good candidates for the classes to be paired up with LIBR 318 are those that require quite a bit of research. Possible disciplines include English, Communication, History, Psychology, etc. Challenges: If we assume 800 graduates each year and a class of 30 students, we will have the same demand for librarian instructors and classroom space as well as all the challenges that we have in Model 1. Teaching Learning Community classes calls for the collaboration between the instructors for the two classes and possible adjustment of course materials on both sides. The link will happen only when there are interested instructors who are willing to spend the time and make the extra efforts to make the link work. Students often do not understand how Learning Community classes work. The descriptions of the Learning Community classes in the Class Schedules are complicated and confusing to the students. When 2 classes are officially linked as a Learning Community, caps for each class and a cap for the combined Learning Community class are put in place in PeopleSoft. During the registration period, someone needs to watch the numbers of the students registering for each class to ensure the full enrollment of the classes if low enrollment in one class occurs. A Learning Community Example: LIBR 318 (1unit) + English Writing 300(3 units) = Writing and Research for College Success (4 units) Page 9 Cap for Writing and Research for College Success = 40 Cap for LIBR 318 = 20 Cap for Engw 300 = 20 One possible scenario is that one class in the link has an enrollment lower than its cap and the other has reached its cap. In this case, we want to break the link so the other class can have a full enrollment. The problem is that PeopleSoft does not monitor enrollment numbers and break the link automatically. Someone has to watch the numbers and get into the system to break the link manually during registration, and this needs to be done in a timely manner to ensure a smooth registration process for the students. It has been a problem for the previous semesters when we have only a few Learning Community classes in place. If we have a dozen such links, with the current PeopleSoft system, we may find ourselves in a chaotic situation. Model 3 – Info Comp Infused in a GE course Typical content of information competency is infused into the instruction of a GE course. The instruction of information competency content is delivered by the instructor in the discipline of the GE course. Model 4 – Info Comp Infused in a GE course – with Auxiliary Modules This model is similar to Model 3 in that the information competency content is infused into the instruction of a GE course, but differs in that students will enroll in a “0” unit course consisting of information competency modules designed and taught by library faculty. Challenges: Identify GE courses and persuade the Deans and instructors to go with the model Students will do more work for the same credit units, namely the units for the original GE course Allocate enough time in the delivery of the combined course to cover LIBR 318 contents in a manner that will meet the Information Competency Standards One possible approach is to combine Model 3 and Model 4 so that the LIBR 318 content will be contained in a self-paced online tutorial. Page 10 Model 5 -- Self-paced online tutorial Self-paced online tutorials have been used by many libraries across the nation as an instructional tool to deliver information competency instructions to the students. Some good examples are SearchPath (http://www.wmich.edu/library/searchpath/) from Western Michigan University Libraries, TILT (http://tilt.lib.utsystem.edu/) from the University of Texas system, Research Blueprint (http://library.udayton.edu/tutorial/) from the University of Dayton library and OASIS, the Online Advancement of Student Information Skills (http://oasis.sfsu.edu/) from San Francisco State University. If approved, the SCC library will develop its own self-paced tutorial to meet its need for information competency instruction. The tutorial will consist of several modules, each focusing on one or more aspects of information competency skills and ending with an assessment for the module. Students will be allowed to take the tutorials and the assessments at any time and for multiple times until they are successful. The online self-paced tutorial can be offered as a self-paced 1-credit class or as a notfor-credit class or as a part of the infusion model. Advantages of this approach include flexibility and convenience for the students, no demand for classrooms, and less need for librarian instructors once it is developed. Challenges: Initial development of such a tutorial. Assessment A challenge mechanism will be in place for students who want to earn the credit by testing out. The challenge test will be based on the Information Competency Proficiency test developed by the Bay Area Community Colleges Information Competency Assessment Project in 2003. The test was developed in line with the ACRL information competency standards and performance outcomes. It consists of two parts, Part A with 47 multiple choice, matching, and short answer questions and Part B with 12 performance-based exercises. Copies of the test have been distributed to the members in the Task Force, Behavioral and Social Sciences Division, Academic Senate and Curriculum Committee in an effort to help the college community understand the issues. Page 11