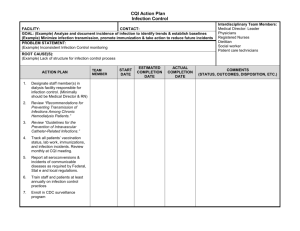

infection control Structure

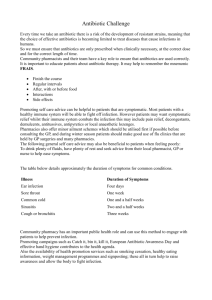

advertisement

UNIVERSITY HOSPITALS OF MORECAMBE BAY NHS TRUST TRUST BOARD MEETING To be held on 25 APRIL 2007 Agenda No 11 Report of: Dr David Telford Director of Infection Prevention and Control Paper Prepared by: David Telford Date of Paper: April 2007 Subject: Infection Control Annual Report Standards for Better Standards for Better Health. C4a,d,c,e; C11; C21; D12b Health Link: Strategic Objectives 1 and 10 Assurance Framework Link: principal Objectives 1.4 and 10.3 Background Papers: In case of query, please contact: David Telford (3770) Purpose of Paper: This is the annual Board update on infection control within the Trust. Key issues: 1. Creditable progress and outcome measures. 2. Loss of a key member of staff. 3. Constraints from capacity problems and the growing number of vulnerable patients. The Board is asked to: : 1. Note the report and concerns. 2. Endorse the forward plan. 3. Support the reappointment of the Nurse Consultant. Relevant guidance and standards: “Getting ahead of the Curve” “Winning Ways” “Going Further Faster” “Saving Lives” Standards for Better Health. C4a,d,c,e; C11; C21; D12b Code of Practice for the Prevention and Control of Healthcare Acquired Infections (The Health Act 2006) Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts Infection Control Team Annual Report 2006 University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS INTRODUCTION This is my first annual report since retiring as Medical Director and it covers the period from October 2005 December 2006 inclusive. It is produced in accordance with the obligation imposed by the Code of Practice for the Prevention and Control of Health Care Associated Infections, issued under the Health Act 2006. I have not adopted the national template for this report, because I believe it would create a very bulky document with a lot of unnecessary detail that would obscure the main issues. This report offers an overview for board members; much of the detail can be found in other reports and documents. There was a five year gap when I was away from front-line practice and I have noticed some major changes. These are having a significant impact on our infection control team and the job has become more complex and busy. With hindsight, these changes have been developing for many years but the gap has thrown them into stark relief. First is the growth in the number of vulnerable patients. This is true in the traditional areas of opportunistic infection such as cancer and transplant surgery. The growth in medical implants and intensive care carries its own burden of infection. But most dramatic of all is the growth in the frail, elderly population. These people have multiple health needs and, whilst modern medicine can preserve life, they are very vulnerable to infection and have poor powers of recovery. They receive frequent antibiotic courses that set the scene for the emergence of antibiotic resistance. This is precisely the group that acquire Clostridium difficile and MRSA and much of the rise in these infections is due the growing at-risk group. Secondly, and consequently, there is more antimicrobial resistance so infection management and antimicrobial choice have become much more sophisticated. Finally, to compound matters, there is a lot of competition for space in the undergraduate medical curriculum and microbiology does not figure as highly as it once did. Junior doctors are now much less microbiologically literate than they used to be and they need more support. Most know this and seek advice but some do not and infection management and antibiotic prescribing need continuous vigilance. So, the Infection Control Team has had a busy year. Carol Magee’s retirement in April 2006 left us without a key member of staff and replacement has been delayed by banding issues. This now resolved and we will be recruiting another Nurse Consultant in the very near future. Whilst we have maintained day to day operational cover, some of the more strategic elements of Carol’s role have been neglected. We are maintaining compliance with the mandatory surveillance requirements and with the support of the facilities director we are keeping up with the burden of regulation and compliance. Ill health in another key member of staff has compromised this but overall we believe our performance is very creditable. There are three elements to hospital acquired infection and they set the format for this report. They are: Personal and environmental hygiene. Antimicrobial resistance. Patient vulnerability. HYGIENE This is central in clinical practice but its efficacy is a matter of conventional wisdom. Surprisingly, there is little hard evidence to support the link between cleanliness and infection but intuitively and aesthetically the principle is sound. High standards of personal and environmental hygiene are foremost in clinical practice and hospital management. Initiatives in the past year were: Personal hygiene We have continued the roll-out of the national “Clean Your Hands Campaign”. This Trust was an early implementer under the leadership of Carol Magee. Implementation was largely complete at her retirement and the Infection control team have kept up the pace up. Hand hygiene has a high profile at medical school and it is gratifying to see the junior doctors setting a good example to their senior colleagues. It is also good to see some visitors using the alcohol gels available at ward entrances and this is a welcome sign of increasing personal responsibility on the part of the general public. Together with the Occupational Health Department we have introduced a Glove Policy. Latex allergy gave the main impetus to this but we have used the opportunity to encourage good practice in glove use. There have been some problems of implementation, mainly around procurement issues and the need for surveillance of staff with skin problems. The policy needs further work and it has been given an early review date. It could well be extended into a more general Hand Care policy. The Board started a stimulating debate on dress and uniform codes to which the team contributed. In general we believe that all ward staff should wear washable cotton fatigues like those worn in theatre and ITU and in many hospitals outside the UK. I form the impression that this is a developing trend in this Trust but rigorous enforcement of this practice would have significant implications for the provision of changing accommodation and for the linen services contract. Most staff appear presentable, and inappropriate dress and excesses in jewellery, makeup, cosmetics and hair style are best addressed on an individual basis. Environmental hygiene This is a continuous struggle. Most clinical areas are also heavily used public areas and the rigid environmental control policies one finds in industry are not feasible. There is a lot of wear and tear so continual cleaning and fabric maintenance are essential and the hotel services department do an excellent job. The occasional lapses and complaints are quickly addressed. A significant benefit here is the overall impression created by a clean well-managed environment. A new consultant who joined us recently remarked that our clean and tidy hospitals, in contrast to the teaching hospitals he had left, were a significant factor in his decision to join this hospital group. Overarching all this are the regular ward hygiene audits performed by the modern matrons under the oversight of the infection control team. These are largely successful and we are able to document resulting improvements. The team is working with departments to integrate the practice observations and improvements set out in the Saving Lives initiative into this audit programme. For external oversight we have the regular inspections by the Patient Environment Action Team and the Patient Public Forum. These are largely complimentary. Many microbiologists agree that Clostridium difficile is more worrying than MRSA. It regularly appears on death certificates although it is often one contributing factor amongst many in a very frail patient. The report on the outbreak at Stoke Mandeville report has set an agenda for many trusts and is central in the ICT’s thoughts. The growth in the numbers of hypertoxic strains and the greater potential for patient to patient spread is forcing a review of isolation facilities. A small allocation of £300,000 from central funds has been spent on completing the mattress replacement programme and expanding isolation facilities at Furness General. There will be a need to improve provision at the RLI and the medicine directorate are exploring options. Decontamination This is overseen by the Medical Devices Group and, since the appointment of Chris Lamb, as medical devices manager the Trust has made great strides in the safety of medical equipment. The infection control team play a full part in the work of this group. The Facilities Directorate completed the refurbishment of the sterilising department at Furness General and the closure of the department in Westmorland General. The Trust now has one of the few fully accredited services in the North of England delivered to the Department’s deadline of March 2007, a vindication of the Trust’s resistance to joining a consortium to build a large centralised facility in Lancashire. After three years, the consortium is still in the very early planning stages. The next phase of the decontamination strategy is to raise the endoscope disinfection facilities to full compliance with the guidance set out in HTM 2030. The Trust is broadly compliant with the major aspects of HTM 2030 but further work is needed on the detail of daily and weekly checks and maintenance. Surveillance Much of the guidance and the external assessments concentrates on process and procedure. There is a danger here that we loose sight of the point and that is a reduction in infection levels. Rates of hospital acquired infection are the ultimate arbiters of the effectiveness of infection control policies. The Health Protection Agency leads a programme to measure rates of surgical site infections (SSI’s or, more prosaically, wound infections) and compare Trust rates to national figures. Participation in this scheme is compulsory and, with support from Stuart Westbrook in the Surgical Directorate, we have been monitoring rates for hip and knee replacement since January 2006. Stuart’s detailed knowledge of orthopaedics makes him a highly effective information gatherer and, with the help of the new theatre management system, data collection is relatively straightforward and not too time consuming. There is little to report here because we have had no infections (fig 1). This unremarkable because, as the national figures show, infection rates Fig 1. SURGICAL SITE INFECTIONS Quarter 3 2006 (Jul- Sep) Cumulative Performance TOTAL HIP REPLACEMENT Hospital RLI FGH WGH Total Operations 27 25 63 Wound Infections 0 0 0 Period Apr - Sep 06 Jul - Sep 06 Jan - Sep 06 Total National Benchmark Total Operations 50 25 154 229 98379 Wound Infections 0 0 0 0 1530 Total Operations Wound Infections 51 0 28 0 124 0 203 87184 0 758 Percent 0.0% 1.6% TOTAL KNEE REPLACEMENT Hospital Total Operations RLI 17 FGH 28 WGH 34 Wound Infections Apr - Sep 06 0 Jul - Sep 06 Jan - Sep 0 06 Total National Benchmark 0 Percent 0.0% 0.9% for these procedures are very low. The real problem in prosthetic orthopaedic surgery is the development of deep infections around the joint because they are very debilitating and difficult to manage and the current surveillance programme does not trap these because they emerge some time after surgery. The programme has been compromised by sickness absence but once our programme has recovered we will consider different procedures. The operations for fractured neck of femur, vascular procedures and colorectal surgery have higher infection rates and should be more useful. ANTIBIOTIC RESISTANCE The link between the levels of antibiotic use and the emergence of resistance is well documented and is an example of evolutionary adaptation. By international comparisons, the UK has been relatively prudent in its use of antibiotics for many years and serious antibiotic resistance problems have been slow to emerge. We continue to control this but we cannot avoid antibiotics altogether – they are life saving drugs. We have an Antibiotic Subcommittee of the Drugs and Therapeutics Committee. It meets approximately annually to review and manage antimicrobial prescribing. It exercises formulary control with levels of restriction ranging from those antibiotics that can be freely prescribed by junior doctors and independent prescribers to those that are only availably on the authority of a microbiologist. The Trust has adopted the consensus guidelines on the management of common medical conditions that is produced by a consortium in the Midlands. We are bringing recommendations on routine antimicrobial into this envelope. Policies and guidelines have their place but they are very blunt instruments and, when combined with the lack of microbiological literacy found in the trainees, they do not encourage intelligent antibiotic use Improving microbiological literacy is a long game. The microbiologists have scheduled teaching sessions with undergraduates and postgraduates but they need more exposure and this will be in competition with other important areas of practice. Medical students and junior doctors are usually keen to seek advice about individual patients and these consultations are used as learning opportunities. Microbiologists have a higher profile nowadays and the role is becoming much more clinical and less laboratory-based than it used to be. For many years the Trusts microbiology department has run a module for BSc students at Lancaster University. This could easily be adapted for medical students and we will be exploring this possibility with the new medical school. Junior doctors frequently look to nurses for guidance on local prescribing practices and nurses can be a formative influence here. The Drugs and Therapeutics Committee is developing independent prescribing. We now have about 10 non medical prescribers with as many in the pipeline. I believe that this agenda can be used to support sensible antibiotic prescribing. Surveillance Fig 2. Antibiotic Spend per Patient Day Oral Antibiotics Blackpool £9 East Lancashire £8 Lancashire Teaching Hospitals £9 Morecambe Bay Hospitals £11 North Cumbria Hospitals £2 Average £8 Intravenous Antibiotics £25 £27 £27 £16 £25 £24 Total £34 £35 £36 £27 £27 £32 Again, it is outcomes that matter. Last summer, the Strategic Health Authority produced some interesting comparisons of antibiotic expenditure that are summarised above (Fig 2). These indicate that antimicrobial consumption in these hospitals is relatively restrained when compared with our neighbours. Clostridium difficile and Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are both phenomena of antimicrobial resistance and their antimicrobial use is a major factor in their emergence. We submit data to the mandatory surveillance programmes and the most recent results are charted below (Fig 3). Again, they essay a creditable performance. Unfortunately, the performance target is a 50% reduction, not absolute levels. This penalises Trusts with very low levels where the costs of further reductions are disproportionate to the gain in patient welfare. I have also included a historical trend of the local figures indicating that, whilst our comparative results are good, there is no room for complacency. Fig 3. MRSA Bacteraemia Rate vs Occupied Beds per Day Clostridium difficile Rate vs Bed Occupancy 4.5 6 5 Cl difficile rate MRSA Bacteraemia Rate 4 3.5 3 2.5 2 1.5 4 3 2 1 UHMB 1 0.5 UHMB 0 0 0 500 1000 1500 2000 0 50000 100000 150000 200000 250000 300000 350000 400000 Occupied Beds per Day HES 2004 over-65 bed-days 250 W GH FGH Trust Totals © David Telford 2007 Number 200 RLI 150 100 50 06 20 05 20 04 20 03 20 20 02 0 Many microbiologists agree that Clostridium difficile is more worrying than MRSA. It regularly appears on death certificates although it is often one contributing factor amongst many in a very frail patient. The report on the outbreak at Stoke Mandeville report has set an agenda for many trusts and is central in the ICT’s thoughts. The growth in the numbers of hypertoxic strains and the greater potential for patient to patient spread is forcing a review of isolation facilities. PATIENT VULNERABILITY Successful disease control rests on a sound understanding of epidemiology – the way diseases behave at a population level. It is epidemiology that elucidated the health effects of smoking, pollution, radiation and industrial diseases and was the scientific basis of the control of many conditions. A significant factor in the epidemiology of any infection is the proportion of the population who are vulnerable; high levels of susceptible people lead to high levels of infection. Increasing life expectancy and modern medical interventions are eminently desirable but there are consequences. The octogenarian population has risen from 2.3 million in 1995 to 2.7 million today; an increase of 17%. Projections run at 4 million in the late 20’s and 6.5 million by 2050; by which time there will also be 1 million centenarians. Many of these are frail and vulnerable to infection. They receive more antibiotics so are open to the emergence of antibiotic resistance and a downward spiral of increasing antimicrobial dependence, increasing resistance, restricted antibiotic choices and, ultimately, antibiotic failure. Managing these “opportunistic infections” occupies a major part of the microbiologist’s day. I believe that this Trust is performing quite well in addressing hospital hygiene and antimicrobial prescribing. However, the success these activities will be constrained by the levels of vulnerable people, by their concentration, and by the length of time they remain exposed to the hospital environment. This growth in the elderly population is probably the single biggest factor in the rise in hospital acquired infections, the one over which we have least control and the one that attracts the least public attention. It is also a significant factor in the rise of “community” healthcare acquired infections. Twenty years ago most of my antimicrobial resistance problems were on the long-stay elderly wards at the Lancaster Moor. Those wards are long since closed but the patients have not gone away. They are now dispersed in nursing and residential homes or, with support, in their own homes and there are many more of them. The problems here are social cultural and ethical, going well beyond the sphere of microbiology. This growth of the vulnerable population will offset the effect of our other infection control activities. OUTBREAKS During the period the Trust has experienced the following clusters of infection (Fig 4). Fig 4 FGH RLI WGH Viral Gastroenteritis 16 14 6 MRSA 0 0 0 Clostridium difficile 3 0 0 It is sometimes difficult to define an outbreak. On an elderly ward, there may be 2-3 patients at one time with diarrhoea of non-infectious origin or there may be a couple of patients with Clostridium difficile or MRSA who have acquired it in different ways. The Infection Control Team adopt a flexible approach in their advice because it is important to strike a balance between patient and staff welfare and the disruption to hospital activity caused by control measures. Each outbreak therefore is managed differently according to the precise circumstances. The Team spend some time explaining these apparent inconsistencies. A noticeable feature recently has been the impact of bed reductions. The initial scale of the outbreaks has not changed but, in Barrow in particular, the Team have commented that the loss of flexibility has restricted options making the outbreaks more difficult to control and they have proved more protracted than in the past. There has been more frequent recourse to restrictions on admissions and transfers with a greater impact on elective activity than in previous years. As with clinical hygiene, the effect of service pressure on infection control is difficult to measure. Perhaps some insight can be gained from international comparisons. Holland is often held up as a model of infection control practice; they have some of the lowest rates in the world. A Dutch colleague who has come to work in this country has compared his hospital in Holland with the one in England. The hospitals are broadly similar in size with some interesting differences in bed distribution. But the main difference is the pressure on capacity with half as many admissions and much lower bed occupancy (Fig 5). Most English microbiologists would contend that the differences in MRSA and Clostridium difficile rates are no mere coincidence. It makes sense intuitively; the less pressure staff are under, the more they can give attention to detail, and it is high personal standards that are the bedrock of sound infection control. Directors should to take this into account when considering further capacity reductions and the infection control team would welcome some dialogue with the turnaround team on this issue. Fig 5. A Dutch Comparison Beds Bed Distribution Single accommodation Intensive Care Beds Annual Admissions Average Bed Occupancy Average Length of Stay MRSA bacteraemias Clostridium difficile NHS Hospital Dutch Hospital 1200 Multi-occupancy bays 10% 39 78,780 97.4% 5.5 days 0.31 / 1000 bed days 1.48 / 1000 bed days 1237 2-4 bed bays Haematology & Paediatrics only 28 34,547 71% 8.9 days 0 0.16 / 1000 bed days INFECTION CONTROL STRUCTURE The Infection Control Team sits at the centre of these activities. It comprises the two microbiologists, the lead nurse and the three site nurses. The accountability arrangements are set out in the appendix. We meet monthly to share experiences, review work progress the infection control agenda. Others such as occupational health, risk management and the Health Protection Agency attend from time to time. Notes are kept from these meetings and are available for inspection. In the past, guidance has always stressed the importance of the Control of Infection Committee but the team has always been sceptical of that. We find it more effective to raise issues in the corporate or departmental forums that already exist. We have had to robustly defend this position at times but accreditation inspections have always accepted our position. Whilst he Trust has a formal infection control committee, it never meets. It is interesting to note that the new Code of Practice makes no mention of an Infection Control Committee, stressing instead the central role of the Team. The Team is supported by five secretarial and clerical staff (3WTE). One of the posts is currently held in the vacancy freeze. The absence of a lead nurse has reduced secretarial demand but recruitment to the post and the demands of surveillance will highlight this loss and we will be seeking to reactivate the post. The Team contribute to the mandatory training programme but this has been at the expense of some of the more focussed departmental sessions. There is an infection control budget line within Pathology but it is almost exclusively staff costs. There is no contingency for outbreaks or unanticipated events. These are absorbed as and when they occur. Together with the Facilities Directorate we are assessing the trust’s control of infection arrangements in relation to the Code of Practice for the Prevention and Control of Healthcare Acquired Infections. We are broadly compliant with all the major aspects and will be making a statement to this effect in our declaration at the end of April. FORWARD PLAN The absence of a lead nurse is now becoming critical. There is much to be done in updating our documentation for the CNST assessment in December. The process is well in hand and we anticipate placing an advertisement soon. Our policies need bringing up to date for the CNST assessment. This is in December but the paperwork is required by August. I will be sixty at the end of this year. Whilst I am in no hurry to retire we need to start succession planning. As with many other specialities, microbiologists are in short supply and, if we cannot recruit, we might need to look at alternatives such as recruiting a public health doctor or infectious disease specialist to the team. We will maintain the programme of ward audits and embrace the Winning Ways initiative in this envelope. We will maintain our extensive programme of work on improving microbiological literacy and antibiotic prescribing. This will help with the target for the reduction in MRSA bacteraemias but we are firmly of the opinion that a trajectory for reduction from our already low levels is microbiologically baseless. We will review trust isolation facilities and make recommendations via the Planning Team. The Medicine Directorate will finalise plans for improving isolation accommodation at the RLI. We will explore improvements to SSI and pursue ways of utilising Stuart Westbrook in this capacity. David Telford Director of Infection Prevention and Control April 2007 Appendix Accountability Arrangements for Infection Control 2007 University Hospitals of Morecambe Bay NHS This diagram sets out the personal and corporate accountability arrangements for infection control in the Trust. The Director of Infection Prevention and Control sits on the Governance Subcommittee and produces an annual report for the Trust Board. The nurses also have a professional accountability to the Director of Nursing through the Nurse Consultant. Corporate Accountability Personal Accountability Trust Board and Governance Subcommittee (Strategic) Infection Control Team (Operational) Chief Executive Director of Nursing Director of Infection Prevention and Control Consultant Microbiologists Nurse Consultant in Infection Control Infection Control Nurse Specialists Microbiology Laboratories Links with other groups Outside the Trust Primary Care Trusts Environmental Health Public Health Medicine Health Protection Agency Strategic Health Authority Infection Control Structure Version 6 March 2007 Within the Trust Clinical Divisions Clinical Governance Facilities Drugs & Therapeutics Health and Safety Occupational Health