Non-work Related Activities at Work

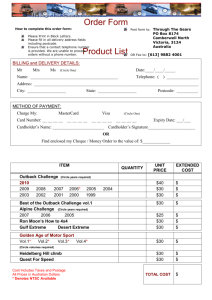

advertisement

Non-Work Related Activities at Work - A Theoretical Framework Patrik Larsson & Lars Ivarsson Karlstad University, Sweden Work in progress… Abstract We know surprisingly little about everyday life in organizations (Ackroyd & Thompson 1999). By convention, the matter of what people do at work has been a managerial concern, focusing on control and surveillance of worker to reassure that they perform the work they are paid to perform. Anything employees do at work which is not work related is usually looked upon as deviant or anti social behaviour. Contrary to this perspective is the academic tradition interpreting non-work related activities in terms of employees' natural resistance, due to the structural subordination of workers (Beynon 1980; Hodson 1991). Common to both traditions, however is the interest in more severe activities (i.e. sabotage and theft), rather than the private matters of an everyday nature. In this paper we point out a fairly unexplored area in the research field, namely private matters of an ordinary character at work. In addition, we present theoretical explanations for employees and employers approaches towards private matters at work. Key Words: Introduction With the industrial revolution an unprecedented separation of time occurred. During working hours, employees were expected to work hard and disciplined in accordance with management’s rules and regulations. All kinds of matters of private concern had to be dealt with in one’s spare time (Hochschild 2001). The division of labour and the organization of work that came along with the industrialization can be regarded as the main cause of a century-old interest for the relation between the spheres of work and leisure among managers and researchers – and in some respect media. The historical heritage which originates from a time when the employer paid wages for hours worked, rather than a specific end result of work still rests heavily on the current working life. Time spent at or on work per se has been – and still are – a sign or even a proof of commitment, loyalty, ambition etc. Work and leisure (spare time) are usually perceived as two separate and rather opposing units (Juniu et al 1996). Although the research field contains a variety of issues, perspectives, and dimensions and ‘the debates are dense and wide-ranging’ (Nolan 2002:118) there have been two main research areas: (a) what people are doing at work, as discussed in the study of behaviour in organizations (organizational behavior), and (b) how work affects people's private lives, often treated in the theories of balance between work and other life (work-life balance). In this project we primarily connect with the first-mentioned tradition to describe and explain a hitherto very sparsely studied area – namely employees’ engagement in private matters of an everyday nature, nevertheless non-work oriented activities. However, we are convinced that the theory of work-life balance, including studies of unpaid work outside working hours, will provide important contributions. Organizational misbehaviour The question what people do at work has traditionally been a concern for management, focusing on control and supervision of employees in order to ensure that they are actually doing the work they are paid to do. Many researchers with a management perspective seem to regard the work sphere as separate from the private sphere of life. The pursuits of organizational efficiency and economic benefits have resulted in an extensive research on desired behavior from employees. As far as desired behavior from a managerial standpoint, Bateman and Organ (1983) use the concept of employee citizenship relating to employee conduct and actions beyond job descriptions and management's stated requirements. Quite often, it is about employees' loyalty and their willingness to contribute to the success of operations. The opposite of such behavior are referred to in terms of organizational misbehaviour which is defined as ‘anything you do at work you are not supposed to do’ (for a critical overview, see Ackroyd & Thompson 1999:2), primarily attracting pro management researchers with a managerial perspective. The focus of this research tradition is especially on deviant behavior of a more serious nature, such as theft, fraud, and sabotage. Furthermore, it seems like anything employees might do at work besides working is seen as deliberate attempts to – in one way or another – harm the organization. Vardi and Weitz (2004:244) summarizes the essence of this perspective with the following definition of organizational disobedience: ‘Any intentional action by members of organizations that defies ans violates the shared organizational norms and expectations and/or core societal values, mores, and standards of proper conduct.’ Despite of this research – or even because of its predominant interest in intentionally behaviour with the (at least partly) purpose of damaging the organization – we know surprisingly little about the perception of, the motives behind, and the importance of everyday, non-work related activities at work (Ackroyd & Thompson, 1999; D'Abate, 2005). Ackroyd and Thompson (1999:3) states explicitly that ‘it is important to recognize the extent of misbehaviour in organizations, if we want to come to a realistic appreciation of the way organizations actually work.’ Taylorization of family life The research on how work affects private life usually takes the employee's perspective – unlike the research on organizational misbehaviour – and implicitly aims to clarify the concerns and difficulties many employees face when it comes to manage and organize work and private life. The assumption that ‘work and family are separate domains that have little impact on each other seems questionable’ (Bedeian et al 1988:475-476). Rather, work and family may be seen as two greedy institutions (Coser 1974) or gravitational fields (Hochschild 2001) that without regard to each other battle for individuals’ time, commitment, and loyalty. A number of studies show that working families are strained to the limit when it comes to manage their lives based on the requirements, demands, and responsibilities that originate from work and private life respectively (Hochschild 2001). A major explanation is altered social structures and gender patterns experienced by individuals in varying degrees. Today, an increasing proportion of women want a successful career as well as a successful family life (Chafetz & Hagan 1996) and more men are interested in balancing working life and family life (White et al 2003). Hochschild (2001:49) concludes that ‘home has gained a newly Taylorized feel’; people strive to as efficient as possible carry out not only necessary chores such as cleaning, cooking and washing, but even more appreciated and desired activities such as to go to the gym, arranging childrens piano lessons, or even spend time with loved ones. Nolan (2002:126) supports this view by reporting how such as shopping, cooking, eating and cleaning up takes so much time that it simply is no room for conversation and emotional support within the family or between partners – ‘the mealtime, rather than being a time for relaxation and catching up becomes a time of tension.’ According to Hochschild (2001), work usually comes out a winner in the conflict between work and family. One explanation, among others, to why people are working so long hours or engage in extensive overtime is that time at work often is perceived more peaceful and even more fun compared to time spent at home. Hochschild (2001:46) gives the following example: ‘Work time, with its even longer hours, becomes a newly hospitable to sociability – periods of talking with friends on e-mail, patching up quarrels, gossiping. In this way, within the long workday of Timmy’s father were great hidden pockets of inefficiency, while, in the far smaller number of waking weekdays he spent at home, he was time conscious and efficient. Sometimes, Timmy’s dad forgot the clock at work; despite himself, he kept a close eye on the clock at home.’ If home really has become a work-like place with little - or even no - room for contemplation, relaxation, or spontaneous fun, people may very well try to compensate that by trying to gain at least some of it during working hours. People's busy schedules outside work may have a tendency to push private matters into the workplace. In line with such reasoning D'Abate (2005) argues that personal businesses at work can be either home-oriented or leisure-oriented. Home-oriented activities are related to family, housekeeping, home maintenance and so forth. It may include contacting a plumber, taking the car to a garage, paying the bills over the internet etc. Leisure-oriented activities are, on the other side related to the individual’s personal pleasures and recreation: reading the paper, surfing on the internet, taking a long lunch and so forth. Work and private life Our point of departure is that a large part of private matters at work and work-related activities in one’s spare time can be explained by the increasingly blurred boundaries between work and private life, combined with each sphere’s craving for an even larger part of people’s time, commitment and loyalty. We are also aware of the importance of structural conditions; wherever people are subordinated, they tend to engage in various forms and degrees of resistance of some kind (Hodson 1991). The trend suggesting that both men and women want to be successful in their work-life as well as their personal life can be linked to the central tenet of identity research, stating that ‘people devote considerable time and energy to constructing and maintaining desired identities’ (Frone et al 1996:58). This obviously creates problems (not least in terms of time) for managing working life and family life. Frone et al. (1996) argue that the demands from family and private life, undermining the individual's potential for developing a work-oriented self-image (dedicated and successful worker) and similarly the demands from work undermine the opportunities to sustain a family-oriented self-image (dedicated and successful parent or spouse). One way to try to solve - or at least manage - this conflict is to establish a sort of mutual availability. It is about trying to be available in varying degrees for work as well as family and other parts of private life at the same time (Bergman & Gardiner 2007). Specifically, it may mean that employees engaged in both private matters at work as work-related activities in their spare time. One result of such a strategy is that work and private life are not kept separate in an obvious way, which can be viewed as a manifestation of the increasingly blurred boundaries between the two spheres (Nolan 2002). Research on the relationship between work and private life has a long tradition and Wilensky (1960) argued early on that there are three possible ways to explain this relationship: spillover, compensation and segmentation. The spillover hypothesis claims that the experiences, perceptions and feelings from one sphere (work and private life) affect the other. The compensation hypothesis suggests that unsatisfactory conditions in one sphere leads to increased commitment in the other, while the segmentation hypothesis argues that working life and private life are two separate unrelated spheres operating independently of each other. The various hypotheses should be considered as ideal types in a Weberian sense, which means that individuals can actually experience all three in varying degrees – ‘it seems more logical to treat spillover, compensation and segmentation as potentially overlapping, rather than competing, processes’ (Sumer & Knight, 2001 : 654). The boundaries between work and private life have become increasingly blurred as in particular work colonizing spare time (Nolan 2002). This colonization encompasses first and foremost actual tasks carried out at home after regular working hours – often without financial compensation (Deming 1994) – but also a performance or exercise of what may be called in terms of semi-related duties or employment matters such as reading trade journals or participate in social activities on one’s spare time. A likely reason for doing is about building a career and/or maintaining an existing one. The colonization also encompasses the aspect of thinking and behaving as a representative of the company even outside the workplace and working hours (Åmossa 2004) together with being available for work even during leisure time (Bergman & Gardiner 2007). According to Hochschild (2001), employers prefer employees who are highly motivated work, who have few personal commitments and obligations and thus can work a lot and constantly be prepared to step in if and when needed. From a management perspective, it is easy to understand how the performance of work tasks and involvement in other work-related aspects on spare time are appreciated and may sometimes also be a demand. Engagement in work on spare time is also seen as an indication or a guarantee of commitment and loyalty as well as a necessity, to varying degrees for a successful career. On the other hand, it is also clear that many people spend time and effort in their work because they like it or even love it. Families today are more likely composed by ‘dual-professional couples in which both partners have careers, not just jobs [and] for both men and women, judging the demands of the workplace and the home has become more difficult’ (Hill et al. 2003:221). Many within the research field have noted the potential or manifest conflict between work and private life. It is, however, an important distinction between the conflict that arises when work interferes with family life and in which family life interferes with work (Greenhaus & Beutell 1985). It seems, nevertheless, that a large proportion of both men and women experiencing both types of conflict (Frone et al. 1996). As more and more men and women find it difficult to combine working life with private life, some employers have discovered the need for special arrangements in order to attract and retain valuable staff. In an article in Fortune Magazine (January 2000) Jerry Useem outlines ‘the new company town’ – a workplace that is not only a place where you work, but a place where you can live: ‘Within the compound’s high walls, people laze on hammocks strung out between pine trees. Others pump iron in the gym, practice their jump shot on the gleaming basketball court, or hang around the putting green, horseshoe pit, or beach volleyball court. Cocks harvest oregano from the herb garden for the day’s meal. Free bananas are everywhere. An array of services – bank, store, dry cleaner, hairdresser, nail saloon – completes the self-contained community.’ The above example can certainly seem extreme. For many the over-lapping of the two spheres (work and private life) consists of less remarkable aspects, such as ‘receiving family-oriented phone calls at work or taking business calls at home’ (D'Abate 2005:1011). Advances in technology make it possible for employers to offer so-called family-friendly solutions (Kylin 2007:5). This can include so-called ‘flex place’ which allows employees to work at home if they so wish. The offer or the opportunity to work at home can certainly be interpreted as a family-friendly arrangement, but detaching tasks from the workplace may also intensify the work demands which can be interpreted as the ‘intrusion of availability for work into family life’ (Bergman & Gardiner 2007:423). Organizational misbehaviour or simply human behaviour Even if the management normally would not object extending the sphere of work – ie employees bring their work home – it is not certain that an expansion of the private sphere at the expense of the work is perceived equally positive. This is based on the belief that when people are at work, they are supposed to work in compliance with management's regulations and thus not engage in any non-work related activities (Pugh 1990). Employee non-work related activities have so far been studied mainly from two perspectives. They are either treated as a natural reaction to the employee's subordinate position and are expressions of the opposition against this position, or they are considered in terms of anti-social and deviant behaviour in general. For the former, we take in labour process theorists who argue that non-work related activities is a natural consequence of the structural contradiction between employers and workers (Beynon 1980; Collinson & Ackroyd 2005). Employees seek autonomy, they are active, creative people and no organizational system can completely eliminate the so-called organizational disobedience (Hodson 1991). A labour process approach suggests that private matters of an everyday nature, conducted during working hours, must be interpreted in terms of expected and natural acts of resistance. Other researchers, predominantly management-friendly, consider the phenomenon in terms of ‘the dark side of organizational behaviour’ (Griffin & O'Leary-Kelly 2004) which includes descriptions of deviant, dysfunctional, antisocial and counterproductive behaviour (Lefkowitz 2006). This perspective includes research on all sorts of undesirable activities and acts: theft, fraud, sabotage, avoidance of work, unauthorized breaks, false sick leave, to be late and/or leave work early, incorrect performance of duties, physical aggression and verbal hostility (Kamps & Brooks, 1991; Johns 1997; Koslowsky 2000, Spector & Fox, 2002, Ambrose et al 2002, Weber et al. 2003; Mulholland 2004; Willison 2006). Even not serving a customer quickly enough is by some considered as deviant behaviour (Franklin & Pagan 2006). According to Harris and Ogbonna (2006:543), scholars have found that between 75 and 96 percent of employees ‘routinely behave in a manner that can be described as either deliberately deviant or intentionally dysfunctional.’ Stroh and Reilly (1997) even wonder whether the organizational loyalty is dead. The loyalty issue is commented in Proffice’s (one of the leading agencies for temporary workers) magazine ‘Dagens Möjligheter’ ([in English: ‘Todays Opportunities’] No 5, November 2007) by a manager at IKEA that says: ‘My view is that employees have abused our trust if they engage in Internet activities such as Facebook and dating at work’ (‘Dagens Möjligheter’ No 5, November 2007) There are many types of behaviour deemed detrimental to the organization (Fox et al 2007) and many actions are also interpreted as deeds with an expressed intent to harm the business (Crino 1994). There are various reasons for why organizational disobedience has generated so much interest, one prominent reason however is probably the assumption that it entails major costs for companies and public authorities (Hollinger 1991). Some argue that it may even put companies into bankruptcy (Oliphant & Oliphant 2001). The economic impact is also recognized by media who gladly foment the debate by reporting on how much money companies lose due to employees talking to each other about non-work related matters, generally expressed as water-cooler conversations and personal Internet usage, known as cyber slacking (D'Abate, 2005). Such statements are based on a belief that if the employee did not engage in a specific non-work related activity – for instance talking with a colleague about this weekend's plans – he or she would have worked instead. Such an assumption appears rather naive. The idea to examine every conceivable non-work related activity is clearly linked to Taylor's efficiency strivings in the early 1900s. Taylor (1911:14) considered that an employees intentionally slow performance of duties (soldiering) was a ‘deliberate attempt to mislead and deceive his employer’ – 100 years later a still widespread idea among those who consider all non-related activities as fraudulent. Even seemingly harmless activities such as use of office supplies – like a printer and copier – for personal use are believed to promote a culture where theft is tolerated (Kamp & Brooks, 1991) and although this hardly results in large economic losses, it is best to nip it in the bud. Some researchers (eg Slora 1989, Franklin & Pagan 2006) advocates that the employees' involvement in non-work related activities should be prohibited and prevented at all costs. Croute (1984) on the other hand, points out that employees are not only workers but also people with private lives and personal interests outside of work, thus it is not surprising that they are actually engaged in private matters at work (D'Abate, 2005). What employees do at work besides working is closely linked to the underlying causes of behaviour in question. Reasons to engage in private matters at work Why do employees engage in personal matters at work? Previously, we argued that the unclear boundaries between work and other life are one important explanation, as well as the structural conditions in the relationship between management and workers. In addition to this, there are also some useful theories that can help to understand the phenomenon. However, it is important to emphasize that some of these theoretical explanations are overlapping, while others are opposites. Although this project is not about criminal activity, we believe theories of white collar crime provide valuable insights as they relate to deviant behaviour among persons who are considered ‘normal’ and well-adjusted. Rational choice theory claims that people act from a self-interest (Kramer & Tyler 1996). This means that employees will engage in private matter if the conditions allow it – if the virtues or benefits are greater than the perceived losses or discomfort. Theories of effort bargaining (Behrend 1957; Baldanus 1961) and equity theory (Adams, 1963) assume employees engage in a kind of informal ‘negotiating’ and try to balance effort and compensation, which is linked to perceptions of justice (Colquitt et al 2006). This means that the experience of working in a broad sense affect the employee's job performance, commitment and motivation (Rainy 1993). Escapism occur when employees engage in personal business or other non-work related activities to physically or mentally escape from work. Noon and Blyton (2002:256) states that ‘voluntary absence (taking a day off) is used by a significant proportion of people as a temporary respite from the pressures and frustrations contained within many work settings.’ To engage in other activities than work during working hours need not always be associated with boring jobs and/or poor working conditions. On the contrary, the reason may be to charge the batteries (reload) which in some ways can be seen as opposite to escapism, although the specific activity – for instance reading a newspaper – in both cases can be the same. Ethical principles, work ethic and group norms (Mayo 1949, Weber 1958; Lysgaard 1961, Terry et al 1999) probably also play into whether, how and to what extent people engage in private matters at work. It is also important to note that an individual's reasons for engaging in non-work related activities may be different at different times. Concretely, this means that more of the above potential explanations may exist for the same employee, perhaps even at times on the same occasion. There is a lack of research explicitly focusing on private matters at work. The research to date has been concerned with this phenomenon have been carried out by D'Abate (2005) and D'Abate and Eddy (2007) based on an interview with 30 people working in offices and also have some type of managerial position and a survey including 115 employees in an office environment respectively. These studies have resulted in (a) a list of concrete activities (office) employees may engage in during work hours, and (b) that it is involved in private affairs as a result of a personal interest and/or to completely easily manage home and family life. D'Abate (2005:1026) points to the need for continued research in order to ‘better understand and define the relationship among home, leisure, and work life realms…’ Managerial views on private matters at work An important aspect of relationship between work and private matters is the issue of legitimacy, ‘it is management that has the power and discretion to define behaviour as acceptable or unacceptable…’ (Ackroyd & Thompson, 1999:75). Theoretically we can distinguish four different attitudes toward private matters during working hours: (a) officially prohibited, (b) seemingly forbidden, (c) permitted, and (d) encouraged. A common perception among management researchers is that the employees' involvement in private matters is, and should be, officially forbidden. One should actively combat this, mainly for economic reasons. There are numerous studies (eg Wattles 1989, Hollinger 1991; Ghiselli & Ismail 1998) as well as media reports about how costly employee non-work related activities are. in October 2000, the British Guardian reported that American employee internet surfing causes annually costs of 35 million dollars and in the newspaper Metro (20 May 2008) one could read that time spent by Swedish employees' surfing the web is equivalent to 430 000 jobs. An article in Business Review, February 2003, argued that the annual basketball tournament, NCAA costs U.S. employers an incredible 1.4 billion U.S. dollars in lost production alone due to the employees discuss the tournament with each other during working hours. Everything according to calculations by the consulting firm Challenger Gray & Christmas Inc. By officially prohibit certain activities – such as private Internet surfing or even non-work related conversations with colleagues (which, incidentally, appears as a highly unrealistic ambition) – seems to some researchers and employers believe that employees would use the equivalent time to work instead of to engage in other types of non-work related activities. Even if employers does not like employees engagement in private matters during working hours not all goes out with the official ban. Some employers choose to turn a blind eye to private affairs as long as no one flaunt their behaviour or things get out of hand. Such an attitude may be cited as the seemingly forbidden, and may derive from a belief that organizational misbehaviour cannot be eliminated (Hodson 1991). Employers’ indulgence to some organizational misbehaviour has to to with an assumption that it prevents even greater damage caused by revengeful workers (Ditton 1977). Employees who are dissatisfied with work and working conditions may also resign and if the person in question is valuable to the organization, this can have extremely severe consequences. A different view of employers may be to actually allow private matters during working hours. The phenomenon is simply not particularly alarming to some, when you look at it as buying employee commitment, rather than some ones time, and a permissive attitude may actually be beneficial in the longer term as a result of the alleged positive side effects such as loyalty, commitment, creativity and productivity, etc. Although it probably is rare, there are also employers who encourage employees to engage in some private matters. Recently, the prevalence of social media ended up in the spotlight and also the question of whether employees should be allowed to use them for private purposes. The Swedish PR-firm JMW encourages staff to use Facebook for private purposes during working hours. This is based on a perception that it ultimately benefits the company, not least because of a conviction of its future value in terms such as product placement, recruitment and advocacy (Dagens Möjligheter, No 5, November 2007). Conclusions Although the massive interest in organizational behaviour, we know in fact quite little about what is actually going on in organizations, or in other words: what people do at work, especially non-work related activities of an everyday nature. In this paper, we contribute by identifying four theoretically managerial standpoints regarding workers’ engagement in non work-related activities: Officially prohibited; seemingly forbidden; permitted; and encouraged. We argue that this classicisation contributes to achieve a more nuanced picture of an often rancorous debate that non-work related activities (usually reduced to the use of social media) are extremely costly and damaging to businesses, governments, and society at large. For some employers it is easy to prohibit and make engagement in non-work related activities impossible, while it is difficult or even unfeasible for others employers to conduct strict control of the labour process. Still other employers make an active choice not to fight against employees’ engagement in non-work related activities due to a calculation that a permissive attitude wins in the long run. The classification of managerial standpoints raises questions of reasons, consequences, and perceived effects. This leads to a need for further scrutinization by questions such as: how do various sectors, industries and categories of occupations influence management views? How important is the hierarchical management structure, e.g do middle management motives and views differ from top management? Besides the classification of managerial approaches, this paper contributes by emphasizing that non-work related matters do not necessarily represent acts of either anti-social behaviour or resistance. Research so far, albeit of limited extent, has shown that the reasons – for primarily home-oriented non-work activities – are oriented towards handling daily life. These studies (D’Abate’s 2005; D’Abate & Eddy 2007) are, however, explorative and limited to American office work. That leaves a wide range of work settings (in a broad sense) to be investigated. To gain a better understanding we need to find out what workers do; why they do it, how they manage to do it, and how they justify non-work related matters at work. A range of factors need to be taken into consideration: Work content; skills; Occupation; Type of employment contract; organizational position; sex; marital status and children at home etc. References Ackroyd, S. & Thompson, P. (1999): Organizational misbehaviour. London: Sage Adams, J. S. (1963): ‘Toward an understanding of inequity’ Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, Vol. 67, pp. 422-436 Ambrose, M. L., Seabright, M. A. & Schminke, M. (2002): “Sabotage in the workplace: The role of organizational injustice” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, vol. 89 (1), pp: 947-965 Baldanus, G (1961): ‘The relationship between work and effort’ Journal of Industrial Economics, vol. 6 no. 3 Bateman, T. S. & Organ, D. W. (1983): “Job satisfaction and the good soldier: The relationship between affect and employee citizenship” Academy of Management Journal, vol. 26 (4), pp: 587-595 Bedeian, A. G., Burke, B. G. & Moffett, R. G. (1988): ”Outcomes of work-family conflict among married male and female professionals” Journal of Management, vol. 14 (3), pp: 475-491 Behrend, H. (1957): ‘The effort bargain’ Industrial and Labour Relations Review, vol. 10, no. 4 Bergman, A. & Gardiner, J. (2007): “Employee availability for work and family: Three Swedish case studies” Employee Relations, vol. 29 (3), pp: 400-414 Bergqvist, T. (2004): Självständighetens livsform(er) och småföretagande. Karlstad University Studies 2004:47 Beynon, H. (1980): Working for Ford. Harmondsworth: Penguin Chafetz, J. S. & Hagan, J (1996): “The gender division of labor and family change in industrial societies: A theoretical accounting” Journal of Comparative Family Studies, vol. 17, pp: 185-219 Collinson, D. & Ackroyd, S. (2005): ‘Resistance, misbehavior, and dissent’ in Ackroyd, S., Batt, R., Thompsin, P., & Tolbert, P. S. (Eds) (2005): The Oxford handbook of work & organization. Oxford University Press Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., Judge, T. A. & Shaw, J. C. (2006): ‘Justice and personality: using integrative theories to derive moderators of justice effects.’ Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100, pp: 110-127 Coser, L. A. (1974): Greedy institutions: Patterns of undivided commitment. New York, The Free Press Crino, M. D. (1994): ‘Employee sabotage: A random or preventable phenomenon?’ Journal of Managerial Issues, vol. 6 pp. 311-330 Crouter, A. C. (1984): ‘Spillover from family to work: The neglected side of the work-family interface’ Human Relations, vol 37, pp: 425-442 D’Abate, C. (2005): ‘Working hard or hardly working: A study of individuals engaging in personal business on the job’ Human Relations, vol. 58, no. 8 D’Abate, C. P. & Eddy, E. R. (2007): “Engaging in personal business on the job: Extending the presenteeism construct” Human Resource Development Quarterly, vol. 18 (3), pp: 361-383 Deming, W. G. (1994): “Work at home: Data from the CPS” Monthly Labor Review, vol. 117 (2), pp: 14-20 Ditton, J. (1977): Part-time crime: An ethnography of fiddling and pilferage. London: Macmillian Franklin, A. L. & Pagan, J. F. (2006): ‘Organization culture as an explanation for employee discipline practice.’ Review of Public Personnel Administration, vol. 26, no. 1 (pp 52-73) Fox, S., Spector, P. E., Goh, A. & Bruursema, K. (2007): ‘Does your coworkers know what you’re doing? Convergence of self- and peer-reports of counterproductive work behavior’ International Journal of Stress Management, vol. 14 (1) pp: 41-60 Frone, M. R., Russell, M. & Barnes, G. M. (1996): “Work-family conflict, gender, and healthrelated outcomes: A study of employed parents in two community samples” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, vol. 1 (1), pp: 57-69 Ghiselli, R. & Ismail, J. A. (1998): ‘Employee theft and efficacy of certain control procedures in commercial food service operations’ Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, vol. 22, no. 2 (pp 174-187) Greenhaus, J. H. & Beutell, N. J. (1985): “Sources of conflict between work and family roles” Academy of Management Review, vol. 10 (1), pp: 76-88 Griffin, R. W. & O’Leary-Kelly, A. M. (Eds), (2004): The dark side of organizational behavior. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Harris, L. & Ogbonna, E. (2006): ‘Service sabotage: A study of antecedents and cobsequences.’ Journal of the Academy of Market Science, vol. 34, no. 4 (pp 543-558) Hill, E. J., Ferris, M. & Märtinson, V. (2003): “Does it matter where you work? A comparison of how three work venues (traditional office, virtual office, and home office) influence aspects of work and personal/family life” Journal of Vocational Behavior, vol. 63, pp: 220241 Hochschild, A. R. (2001, 2. ed): The time bind. When work becomes home and home becomes work. New York: Holt Hodson, R. (1991): “The active worker. Compliance and autonomy at the workplace” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography” Vol. 20 No 1 pp. 47-78. Hollinger, R. C. (1991): ‘Neutralizing in the workplace: an empirical analysis of property theft and production deviance’ Deviant Behavior, vol. 12, pp. 169-202 Holmberg, C. (1993): Det kallas kärlek. Göteborg: Anamma Förlag Huzell, H. (2005): Management och motstånd. Offentlig sektor i omvandling – en fallstudie. Karlstad University Studies 2005:45 Johns, G. (1997): ‘Contemporary research on absence from work. Correlates, causes and consequences.’ in Cooper, C. and Robertson, I. (Eds.) International review of industrial and organizational psychology 1997 (pp.115-173) Chichester, UK: Wiley Juniu, S., Tedrick, T. & Boyd, R. (1996): ”Leisure or work? Amateur and professional musicians’ perception of rehearsal and performance” Journal of Leisure Research, vol. 28 (1), pp: 44-56 Kamp, J. & Brooks, P. (1991): ‘Perceived organizational climate and employee counterproductivity’ Journal of Business and Psychology, vol. 5, no. 4 pp. 447-458 Koslowsky, M. (2000): ‘A new perspective on employee lateness’ Applied Psychology: An international Review, 49 (pp. 390-407) Kramer, R. M. & Tyler, T. R. (1996): Trust in organizations. Frontiers of theory and research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Kylin, C. (2007): Coping with boundaries – A study on the interaction between work and nonwork life in home-based telework. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, Stockholm University Lefkowitz, J. (2006): ‘The constancy of ethics amidst the changing world of work’ Human Resource Management Review. Vol. 16, issue 2 Lysgaard, S. (1961): Arbeiderkollektivet. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget Mayo, E. (1949): The social problems of an industrial civilization. London, Routledge Mulholland, K. (2004): ‘Work place resistance in an Irish call centre: slammin’, scammin’, smokin’, and leavin’’ Work, Employment, and Society, vol. 18, no. 4 pp 707-724 Nolan, J (2002): ”The intensification of everyday life” in Burchell, B., Lapido, D. & Wilkinson, F. (eds): Job insecurity and work intensification. London: Routledge Noon, M. & Blyton, P. (2002): The realities of work. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan Oliphant, B. J., & Oliphant, G. C. (2001): ’Using a behavior-based method to identify and reduce employee theft’ International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, vol. 29, no. 10 (pp 442-451) Pugh, D. S. (1990): Organization theory. Selected readings. London: Penguin Books Rainey, H. G. (1993) ‘Work motivation’ i Golembiewski, R.T. (red): Handbook of organizational behaviour.’ New York: Marcel Dekker Inc Robinson, S. L. & Bennett, R. J. (1995): ‘A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study’ Academy of Management Journal, vol. 38, pp: 555-572 Schough, K. (2001): Försörjningens geografier och paradoxala rum. Karlstad University Studies 2001:19 Slora, K. B. (1989): ‘An empirical approach to determining employee deviance base rates’ Journal of Business and Psychology, vol. 4, no. 2 (pp 199-219) Spector, P. & Fox, S. (2002); ‘An emotion-centered model of voluntary work behavior. Some parallels between counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior.’ Human Resource Management Review, vol. 12, issue 2 Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1998): Basics of qualitative research. London: Sage Stroh, L. K. & Reilly, A. H. (1997): “Rekindling organizational loyalty: The role of career mobility” Journal of Career Development, vol. 24 (1), pp: 39-54 Sumer, H. C. & Knight, P. A. (2001): “How do people with different attachment styles balance work and family? A personality perspective on work-family linkage” Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 86 (4), pp: 653-663 Taylor, F. W. (1998 [1911]): The principles of scientific management. Atlanta: Engineering & Management Press Terry, D. J., Hogg, M. A., & White, K. M. (1999): ‘The theory of planned behaviour: Self identity, social identity and group norms.’ British Journal of Social Psychology, vol. 38 (pp 225-244) Vardi, Y. & Weitz, E. (2004): Misbehavior in organizations: Theory, research and management. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Weber, M. (1958): The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism New York: Scribner's Sons Weber, J., Kurke, L. B. & Pentico, D. W. (2003): ”Why do employees steal?” Business & Society, vol. 42 (3), pp: 359-380 White, M., Hill, S., McGovern, P., Mills, C. & Smeaton, D. (2003): “High performance management practices, working hours and work-life balance” British Journal of Industrial Relations, vol. 41 (2), pp: 175-195 Wilensky, H. L. (1960): “Work, careers, and social integration. International Social Science Journal, vol. 12, pp: 543-560 Willison, R. (2006): “Understanding the offender/environment dynamic for computer crimes” Information Technology & People, vol. 19 (2), pp: 170-186 Åmossa, K. (2004): Du är NK! Konstruktioner av yrkesidentiteter på varuhuset NK ur ett genus- och klassperspektiv 1918-1975. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International