The George Washington University - Department of Political Science

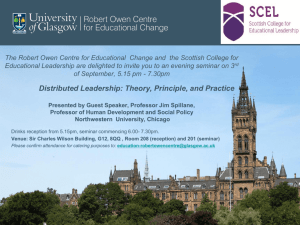

advertisement