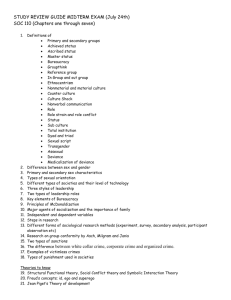

WJEC Crime revision booklet

advertisement