Dr Tanja Mihalic File:Tanja/Eva

advertisement

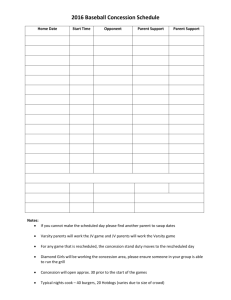

Dr. Tanja Mihalič Faculty of Economics University of Ljubljana 50th Anniversary of the Faculty of Economics International Conference 18.-19. September 1996 Ljubljana File:50let96/50letang.dot/30.7.96 CONCESSIONS TO NATURAL GOODS IN COUNTRIES IN TRANSITION BASED ON A CASE OF THE TOURIST INDUSTRY Key words Concessions, natural goods, valorization of natural goods, tourism, tourism/tourist rent, environmental rent, negative external effects, transition, economic development, environmental management. Summary Nowadays most of economists share the opinion that environmental protection and economic growth are not essentially contradictory. With a transfer of economic thinking or market mechanisms to the area of environmental goods - based on property rights - this integration is possible. Modern market economies are based on formal property rights which facilitate the transfer of resources to their highest-valued use. Countries in transition will have to develop mechanisms to make their markets work and adjust the economic development to the (natural) environmental protection. Concession granting to natural goods is one possible way. For the reason that natural goods are part of tourism supply, they can be valorized from the side of the tourist enterprises on the tourism market. Tourist enterprises valorizing natural goods of better environmental quality, ceteris paribus, can set a higher price. If natural goods are to be considered as free public goods, tourist enterprises valorize them to their own benefit, on the basis of the difference between the total revenue, production costs and profit. This results in the usurpation of the revenue from “selling natural attractions” from the side of tourist enterprises. Valorization value of natural goods through tourist demand is shown by the increases revenue due to producer, consumer and environmental rent and negative external costs. Due to the above mentioned elements of tourist revenue this article structures the total revenue of the tourist company into production costs, environmental costs (in form of environmental taxes), tourist producer rent, tourist environmental rent and profit. With this model the impacts of the tourism concession granting on the development are studied. 1. INTRODUCTION Nowadays most of economists share the opinion that environmental protection and economic growth are not essentially contradictory. There is no doubt that negative economic growth would only lead to a higher degree of poverty and thus the possibility of preventing environmental and other catastrophes would be even smaller. Therefore “environmental protection should constitute an integral part of the development process” (Frost, 1993, p.57-58). With a transfer of economic thinking or market mechanisms to the area of environmental goods this integration is possible. Different values of economic growth rates that were reached in the past, or which are being reached today by more or less market-oriented economies, have divided the world into developed 1 and undeveloped countries. Some economists believe that the property rights are the basic reason for such division of the world (Sotto, 1993, p.8), and herewith the basic reason for achieving various values of economic growth rate and different values of gross domestic product. Property rights are a precondition for a market to function. The difference between developed and underdeveloped countries is not, that the former have markets and the latter do not. Modern market economies generate growth because widespread, formal property rights permit massive, low-cost exchange and facilitate the transfer of resources to their highest-valued use (Sotto, 1993, p.8). Therefore countries in transition have to adopt legislation that will allow the establishment of property rights to natural goods so that they could efficiently be included in the economic processes. If there is no formal owner the planning horizon is shorter and the use and exploitation of natural goods is less productive. In effect no one is responsible for the environmental protection and management. Due to the above mentioned economic and environmental factors, the countries in transition try to speed up their process of privatization. Although allocation of environmental goods should be carried out by market mechanisms, intervention by the state is unavoidable. Granting of concessions is one possible way of making natural goods available on the market as soon as possible. Very slow adoption of laws in this area and herewith a slow introduction of concession relationships into practice, result in very high costs and a lower revenue of the state and local communities. The slow transition to the management of natural goods extends the speculation period, restrains the development of market mechanisms and enables privatization of the existing monopolies of natural goods in the form of a private profit. Inevitably the prospect of environmental damage is increased. 2. THE TERM CONCESSION Originally the word concession (lat. concessio derived from concedere = permit, allow)1 referred to land. The holder of a concession (a country) was given and guaranteed economic power and sovereignty of a particular territory or was even given the right to build trade routes, military bases and trade ports. Concession to public services was developed at the beginning of 20th century (Grilc, Juhart, 1991, p.13). In the developed countries the concessions enabled “privatization” of public services which in the past were only a domain of the state (distribution of gas, water, electricity). Public service efficiency was increased and the government maintained the regulation role. 2 Concession granted for the exploitation of mines, forests or rivers was known in the Middle Ages (Popov, 1991, p.3). The range of activities which are granted concessions to natural goods is unlimited and tourist activities are among them. In history there are known to have been some cases of granted rights to mineral and thermal waters for tourist business purposes (Grilc, Juhart, 1991, p.15). Lately concessions 1 There are a variety of definitions of the term concession. The following are most common: 1. a formal right to use an area for a particular purpose, yielded by the state; 2. a territory to which a right is given 3. a right of exclusive sale of a certain product, gained by the producer; 4. permission to a tax payer to pay lower taxes with the purpose of encouraging export, employment etc. (tax concession) (Adam, 1990, p.98, Collin, 1987, p.58); 5. yield of exclusive right to a natural good (Gabler, 1988, p.2976). 2 Regardless of the distribution criteria, Grilc and Juhart point out the following concessions: trade concession, license concession, franchise concession, real estate concession etc. (Grilc, Juhart,1991, p.15). 2 have been given for tourist activities in national parks (Pauly, 1996, Yosemite News, 1996), for artificial snow coverage of ski-runs, for the utilization of areas as ski tracks etc. 2.1. Concessions to natural goods These concessions refer to natural goods that are a very heterogeneous group (see Figure A1 in Appendix).3 They can be stock and flow natural elements (for example mineral ores, water), natural national assets (for example, state owned parks) and non-expandable natural resources (natural treasure) (for instance, stalagmites and stalactites in caves, parts of the natural and cultural environment). The concession to a natural elements refers to the right of economic exploitation of a renewable or a non-renewable natural resource. The concession to a natural treasure shall concern the right to its management, use or exploitation, whereas the right to exploitation does not apply to the natural national asset (The Environmental Protection Act, 1993, Art.21). Concessions are granted for economic exploitation, management and use of natural goods. In this context the definition of the concession is a relevant one, especially with regard to the exclusive right to a public good for a particular activity (Gabler, 1988, p.2976), which in our case is the tourist activity. Concessions are given by the owner of a natural resource (hereafter “the grantor”) as a repayment right for a stated period of time and under the stated conditions. In distinction from public service concessions (these services are in most cases additionally subsidized by the state), the fiscaleconomic benefits of concessions to natural goods are usually in favour of the grantor (Popov, 1991, p.4). Apart from the above mentioned financial interest, the reason for the interest of the government in giving concessions to natural goods lies in the unrenewability and relative scarcity (monopoly) of natural goods. As natural goods are owned by the whole community, there is always public interest in their maintenance and protection. This of course does not exclude the interest in their valorization. Governments have a responsibility to enable economic valorization of natural goods under the terms and conditions which are considered to be of wider interest to the community of present and future generations. Their responsibility is also to provide environmental management, while fulfilling the difficult task of maintaining economic development (Frost, 1993, p.70). 3. VALORIZATION OF NATURAL GOODS IN TOURISM Tourist countries, regions, places and tourist companies located in such areas, promote natural public attractions as beautiful countryside, karst caves, beaches, clean water, etc. Payment for the “consumption” of natural goods is included in the (“higher”) price of tourist services which emanates from greater tourist demand because of the attractiveness of the natural goods. Reduction in the value of natural goods due to tourist exploitation and pollution, may be categorized as negative 3 Concessions to public service management are regulated by the separate acts (Zakon o zavodih, 1991 in Zakon o gopodarskih javnih službah, 1993) concessions to management, use and exploitation of natural goods are regulated by the Environmental Protection Act (1993). 3 external effects. This may be considered as social costs which are not included in the financial statement of the tourist enterprise. In practice this can be seen as visual pollution of the countryside because of inappropriate tourist utilization of the area, pollution of water and other forms of degradation of the environment such as noise, congestion, destruction of flora and fauna etc. Figure 1: Tourist Supply TOURIST SUPPLY II I Natural attractions (natural goods) Tourist infrastructure Tourist superstructure Socio-cultural attractions General infrastructure Source: According to Kaspar, 1991, p.64-67 and Fischer, 1985, p.38. The above mentioned definition of the theory of public goods in tourism is sufficient as long as we insist on the fact that natural goods in tourism are part of tourist supply (Figure 1) and that they are valorized indirectly, through (“higher”) prices of tourist services. Provision of tourist services (for example: accommodation services, catering services etc.) under the common term tourist superstructure usually refers to the setting up of a general and tourist infrastructure (roads, hotels, promenades). Both the tourist superstructure and infrastructure are complementary and valorization of natural goods in tourism is only possible if both of them exist. However, each of them uses and utilizes the natural environment or natural goods. Since natural goods are usually at everyone’s disposal (public), they have no price, and are available free of charge, companies realize part of their income through their valorization. If property rights to natural goods are not determined, this part of income belongs to the company, which in the past succeeded in usurping the use of some public good (for example sea, beaches, karst caves etc.). It is an established fact that the companies themselves are not willing to admit that they use and exploit natural goods and thus cause social costs (negative external effects) and may lead to a greater private income on account of exploitation and destruction of natural attractions. Property rights to these goods is a precondition for a market-based solution to the allocation problem of natural resources. If natural goods can be valorized as part of the tourist company income generated by a performed tourist activity, and if the owner of natural goods is known, it is quite obvious that the owner wants to have this part of the income for himself. As natural goods are destroyed because of some economic activities, it is also obvious that financial sources must be provided for their protection. The owner of natural goods needs to act as a guardian of the natural goods and should be 4 interested in their protection, which is also connected with certain costs. Although the economic success of tourist companies depends on the quality (attractiveness, purity) of natural goods, the companies are not willing to take responsibility for the costs, especially not those related to the abolition of environmental degradation which was caused in the past and the consequences of such environmental damage.4 3.1. Forms of natural goods valorization If natural goods are to be considered as free public goods, tourist enterprises valorize them to their own benefit, on the basis of the difference between the total revenue and production costs (including normal profit). This results from the usurpation of the income from selling natural attractions and the differences in the environmental quality of the “usurped” attractions when the exploitation costs and the costs of environmental pollution or destruction are not calculated. 3.1.1. Tourist producer rent Valorization value of natural goods through tourist demand is shown by the tourist rent. The amount of the tourist rent equals the entrepreneur’s income because of the production factor of the natural good whose supply is limited. This is the economic rent that belongs to a supplier of any production factor which has a limited supply (Samuelson, 1995, p.243). The tourist-rent size is determined by the value of a tourist product, related to the natural good. If there is no ownership of natural attractions or if the natural goods are public goods that can be exploited by everybody free of charge, the rent is collected by the producer of tourist services. In the opposite case it belongs to the owner. The size of the (tourist) economic rent on the basis of public goods depends on the elasticity of the supply curve of public goods. The more inelastic the supply the greater the economic rent, ceteris paribus. If there is a limited number of karst caves, square kilometers of sea coast and river banks, etc. the supply will be limited. In an extreme situation, with a totally inelastic supply curve in case of monopolistic public goods, the rent depends exclusively on the amount of demand and as a whole belongs to the owner of the natural good. Supply of the owner can exist even if there is no demand and the economic rent is zero. The economic rent based on the exploitation (valorization) of natural goods is realized by the company through the above described functioning of market mechanism. By granting to companies the exclusive right to the management, exploitation and use of the natural goods, the state also enables them a monopoly. Part of the company profit is generated through the economic or monopoly tourist rent. This part of the profit belongs to the owner himself since he is the owner of a natural good. Therefore, in a market-based determination of the concession value, it is considered that the concessionaire pays this amount to the grantor. 4 There is a paradoxical situation in tourism: tourism that needs a high quality environment at the same time also destroys it. A long-term and sustainable development of tourism requires preservation and protection of the quality environment. In the opposite case the tourist demand moves in the direction to environmentally more attractive (less polluted) destinations. 5 3.1.2. Tourist consumer rent Tourist enterprise operating on the basis of concession to natural goods through the whole year, does not succeed in valorizing natural goods for the period of the whole year because the tourist demand varies from season to season. In the non-seasonal period the producer’s rent turns negative and changes into the consumer rent. Out of season the tourist enterprise often has a loss and the prices are set below the total costs per unit, in order to minimize the loss which would be created due to a too low demand out of season, even if the company stops operating for a certain period. The difference between the tourist service price and the unit costs is the consumer rent. A decreased demand out of season is a result of decreased attractiveness (quality) of natural attractions to the consumer in certain months of the year. The source to cover the loss outside the season is the surplus earned during the season. From the owner’s viewpoint it is reasonable to grant concessions to natural goods utilized by tourist enterprises only if the difference between the rent of the producer and the consumer is positive and can be collected by the owner. In case the difference is negative and the concession refers to a natural good which is national natural treasure and therefore the state is interested in making it available to visitors, a negative value of the concession may be reasonable. In this case the loss in dealing with concessions would probably be covered from the budget (financing certain activities, subsidies, tax relief etc.). 3.1.3. Environmental rent A hotel, located by the sea realizes the location rent on the account of a higher selling price in comparison to a hotel located further inland. Two functionally similar hotels on the coast can have different selling prices if the sea near the hotel A is clean and suitable for swimming and the sea of the hotel B is polluted and not suitable for swimming. In this case the hotel A puts into effect the environmental rent, which is formed because of better environmental quality 5 (Mihalič, 1995, p.17). Empirical research on tourist demand has shown that attractiveness of the countryside and other factors of natural environment, like pure air, unpolluted waters and peacefulness, are very important for the choice of destination (Tschurtschenthaler, 1986, p.117). Tourist demand is sensitive to the quality of the natural environment (environmental elasticity) 6. Tourist enterprises valorizing natural goods of better environmental quality, ceteris paribus, achieve a higher rent, because they can set a higher price. This additional surplus earned on the basis of environmental elasticity of tourist demand is called environmental rent. This rent should belong to the owner of the unspoiled environment or to the “creator," i.e. the investor in the quality improvement of the environment. Even if the company (or anybody else) invests in the reduction of the burden to the environment, it should be entitled to the rent earned on this basis. 5 The term ecological (environmental) quality refers to the quality of (natural) attractions of a tourist place, which can be made worse by the man’s activity. 6 Because of the blossoming of the Adriatic sea in the year 1989 the number of tourist accommodation in Rimini (Italy) decreased by almost 50% (Becheri, 1990, p.230). 6 Existence of a positive environmental rent could be denied, if it is assumed that the owner of a natural good is entitled to the rent based on the ownership of the environmentally flawless natural good.7 In many countries in transition this would not be possible. The state, as the owner of natural goods, has taken over the resources that are quite often in a very bad environmental condition. There arises a question, related to the environmental rent (in this case it can be considered as negative), as to who is going to pay the rehabilitation costs of the natural goods. Probably it would not be possible to put into effect the principle of the damage causer referred to the past, as in this case the culprits of the negative external effects in the past should also be known. The anticipated environmental rent, which would be collected by the future investor (this could be the state) for investments in the quality improvement of the environment, would solve the accumulation problem for this kind of investments as well as the problem of the time difference between the starting point of the investment and its first results or the time when the environmental rent is put into effect (for example, various kinds of environmental taxes). 3.1.4. Negative external effects Absence of market mechanisms in the area of natural public goods leads to negative external effects. Internal costs of companies differ from the costs paid by the society to the benefit of the companies. Tourist enterprises that exploit and also destroy the natural environment as a consequence of their activities are not willing to bear costs for its conservation and cleaning. A classical way of solving the problem of negative external effects are ecological or environmental taxes. Another possible way is the introduction of concessions. The owner of natural goods can dictate the exploitation and usage of the natural resources through a concession deed and thus reduce negative external effects or even insist on their abolition. Negative external effects that are not included in company costs, may occur as a fictitious higher income of the company or a tourist producer rent. If a government has not abolished negative external effects but it claims the right to the rent on the basis of the difference between the individual producer unit costs and market price, it should adopt the costs of the maintenance of the environmental quality. If negative external effects are internalized into the company costs, this rent would, in any case, be lowered by the amount of the internalized costs. The result would be the same in both cases. Therefore concession granting does not exclude ecological taxes and other instruments of ecological policy for the internalization of external effects. Furthermore, a private company is entitled to internalization of eventual positive external effects that are caused by its functioning. 4. IMPACT OF CONCESSIONS TO NATURAL GOODS ON THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN TRANSITION 7 This can be the economic diferential rent I, if it is assumed, that natural goods of the same group are of different quality. It can be differential rent II, if for a higher quality of a natural good additional investments are required. In this case the investor’s entitlement to the effects of the investments can be explained with the theory of positive external effects. 7 The purpose of granting concessions to natural goods is to speed up economic development and assure preservation and protection of the natural environment. In the countries in transition granting of concessions is confronted with difficulties. These are mostly related to: 1. problems of legislation (adoption of legislation is too slow), 2. ownership, 3. information and 4. quality of natural goods. 4.1. Legislation problem In countries in transition changes are gradually introduced with adoption of regulations and rules. In Slovenia the concession to natural goods was legalized with The Environmental Protection Act (1993); a more detailed clarification of natural goods (except water as a natural resource) will be introduced by other laws (Kovačič, 1994, p.6). Three years after the adoption of the Environmental Protection Act there are still no regulations which would allow granting concessions to natural assets, natural treasures and natural resources (except water). 4.2. Ownership problem Land and many buildings that were set up for the purpose of valorizing natural goods, are already in private hands or are being privatized. Thus in the countries in transition various subjects can be involved in the process of concession granting. There is the state or local community as a concession grantor. A concessionaire is an enterprise that provides services to which a concession is granted. The concessionaire can also be owner of the real estate involved in the activity he performs. 8 A third person may be the owner of real estate. The reason for the distinction between the two subjects lies in the fact that real estate is connected to area (location) and is therefore immobile, while the concessionaires can change. The latter is necessary if we want to achieve a market-based price determination of the concession for certain activities. The problem can be avoided if the state buys the real estate and thus becomes its owner. Yet this probably would not be a good solution with regard to the buildings of tourist infrastructure, which are subject to valorization of natural attractions, as it is assumed that the state is a bad manager. The problem of real estate can be solved in many ways.9 The grantor is allowed to buy out all the fixed property which refers to concession granting. In the case of a buyout there are two possible buying processes: either money can be used, or a free-of-charge concession is given to the exowner for a certain period of time. When the concession contract expires the grantor becomes owner of the real estate. Land as a natural resource is not mentioned separately because it can be part of a public natural asset, and “thus it is impossible and irrational to deal with it separately” (Dekleva et all, 1993, p.329). “For example, in many countries surface rights are distinct from mineral rights and the government retains the mineral rights even though the land is privately owned” (Gaudet et all, 1995, p.715). 8 9 The Environmental Protection Act (1993) allows expropriation of the real estate and gives the state a preemption right if the real estate is situated on a territory which has a status of a protected natural treasure (Article 20). According to this act water, minerals or mineral ores, wildlife, fish and other wild water flora and fauna in open waters and fishing seas is the property of the state (Article 17). The property on the national assets and nonexpendable natural resources will be defined by other acts (Kovačič, 1996, p.38). In Croatia preemption is based on automatic concession and tax reconciliation with the investment value (Velkavrh, 1996, p.259). 8 4.2.1. Free-of-charge concession to natural resources In the transition period free concession may solve the problems related to the ownership of real estate. With free-of-charge concessions the rights of the grantor and the real estate value of the concessionaire can be reconciled. When the length of time of free-of-charge concessions is calculated the real estate value on a certain day10 and the interest payments for the time of financing should be considered. A further question arises regarding whether the tourist rent that was collected by the company on the basis of a right to natural goods, should also be determined. In theory the question of reduction in the valorization value of natural goods made by the exploiter in the past, also arises. When the period of free concession expires the state could freely look for the best concessionaire. In this manner competition would be created in the demand for concession and the market price of the concession could be formed . 4.2.2. Priority and exclusive right of granting concession to natural goods The problem of a free-of- charge concession given to the existing exploiter of a natural good refers to the priority or even exclusive right to concession. The Slovene Environmental Protection Act determines a market-based concession granting with a public tender except when the concession is locally conditioned.11 Local conditioning is related to the owner of real estate which is needed for a certain business activity connected with the exploitation of a natural good. The state may yield real estate ownership to the present owner and give him the concession to use and manage the place. If the real estate owner is one person, the manager or performer of the activity another, two concessions should be given: one to utilize the real estate location and another to perform the activity. For instance, the relationship between the real estate owner and concessionaire in terms of performing for instance catering activity, should be ratified with a contract. A possible solution would be also sub-concessions. Such examples can be found in national parks, where a national park organization is first granted a concession of managing the park and then it itself enters into a concession contract on individual activities (for example: climbing, catering industry etc.) (Yosemite News, 1996). 4.3. Information problem 10 A different way of assessing the company value is economically unjustifiable. Suggestions that the past investments in real estate need to be assessed and then discounted to the present value are not market-oriented. The assessed value of the real estate on a certain day may differ from the value of the real estate investments, expressed in prices on the same day. In case of a sound investment (on average) and an appropriate maintenance of the real estate in the past, the two values should be equal. 11 Or if the right to exploitation, management or use of a natural good has already been determined by a legal act (Zakon o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o varstvu okolja, 1996, Art.111a). 9 The model assumes that the information about the company’s total costs and the normal profit, which enables the concessionaire an (average) efficient performance according to the invested capital, is available.12 In practice only the company knows the real operating costs. It is assumed that countries in transition have no mechanisms to calculate the size of the tourist rent, so they calculate it indirectly as a surplus of a normal profit which is required by the company itself. As the company has a certain influence on the operating costs and herewith on the size of the reported profit, the competition of the potential concessionaires would lead to cost minimization and an increase in (the reported) profit. As valorization of natural goods requires different kinds of invested capital that vary from case to case, also the size of the capital has to be considered (profit on capital). The grantor of the concession cannot claim possession to an equal percentage of the total revenue earned for different activities (for instance: tourist guiding in a national park, catering industry). On the market natural goods are valorized on the basis of a higher total income, which is realized by the tourist company because of the presence of the natural attractions. Total income and profit growth do not always move in the same direction (for example: diminishing returns, exaggerated costs). Therefore it would be better if the concession value depended on the total income and not profit. Total income is also a better indicator of the volume of business, which is often a critical category if protection of natural goods is concerned. An increased volume of business (for instance number of visitors) means a greater exploitation or destruction of environment. This is a problem of negative external effects and environmental rent again. 4.4. Problem of environmental quality Environmental quality is explained in the chapter on environmental rent. When a natural good is so polluted, that it can not be valorized in a tourist sense, the repayment concessions of performing a tourist activity cannot be granted because a tourist rent does not exist. So an agreement can be made that only those natural attractions can be given repayment concessions, whose environmental quality satisfies certain standards, which enable their tourist valorization. Various mechanisms can be introduced to speed up the cleaning of the environment for the purpose of (future) tourist valorization.13 4.5. A model In the model it is assumed that the countries in transition grant the first concessions to natural goods mostly to companies which already have valorized these resources and have also made certain investments into them (priority and exclusive right to the concession granting conditioned by the real estate ownership). It is assumed that the grantor has solved the problem of asymmetrical information with the mechanisms which prevent the costs exaggeration by the concessionaire. The model also takes into consideration the assumption that the quality of natural goods can be poor and 12 More about see Gerard et all, 1995, p.716-741. 13 There are quite a few examples. Also in Slovenia there are projects, which try, with help of tourist development and because of it, to clean the natural environment which was very degraded in the past (the lake - Šaleško jezero). 10 therefore investments into the improvement of the environmental quality will be needed as only in this way a full valorization is possible. In the model (Figure 2) it is assumed that the operating costs of the company are 50 units (without environmental taxes and charges to the owner of natural goods) and that 20 profit units stand for normal profit according to the invested capital. Costs and at least a normal profit are therefore fixed categories. In the first phase, when the owner of natural resources does not exist and the resources are usurped by private companies, their profit is also made on the basis of the quasi ownership of the goods in the amount of 50 units. When for instance the state appears as the owner of environment it requires a share of the company profit above the normal one for itself. In our case this amounts to 30 units. If the state moves the negative external costs or the environmental costs caused by the company directly to the company, for instance with environmental taxes T (in the model this is 10 units), this increases the costs of the company. Since the entrepreneur still insists on a normal profit on the invested capital, the state will get only 20 units. If the environmental rent is also included in the model, then only 10 units are left to the owner on the basis of his property rights, except in the case that the owner himself invests in the quality improvement of the environment. Figure 2: Structuring the total revenue of tourist enterprise Step TC PF R T ER TR I 50 50 - - - 100 II 50 20 30 - - 100 III 50 20 20 10 - 100 IV 50 20 10 10 10 100 Legend: TC - total costs of the tourist service production, chargeable to the company (without costs of degradation or destruction of the environment, without contributions to the owner of natural goods) PF - profit which remains in the company R - rent on the basis of the title to ownership of a natural good, which belongs to the owner of the natural good T - pollution costs, internalized negative effects (for example, environmental taxes or charges imposed on pollution of the environment caused by the company; according to the ‘polluter’s should pay’ principle they are chargeable to the company; payment for pollution certificates, environmental book-keeping etc.) ER - environmental rent belonging to the investor for the improvement of the environmental quality (may also be anticipated environmental rent, for example, environmental tax for a particular purpose) TR - total revenue In the model the concession granting to pre-existing exploiters of natural goods does not affect the economic growth immediately, yet it does have an influence on the improvement of the environmental quality, maintenance of the environmental quality and reallocation of the income share from companies to the state. In the model the current situation is assumed, i.e. the invested capital and operating costs of the company. Thus, in countries in transition concessions will probably be granted on the basis of priority or even exclusive rights to the present users of natural goods. The first impact on the economic development will be the structural changes in the economy as a result of investments 11 into environmental industry and in the long term a higher valorization value from the exploitation of natural goods will be assured. The dynamic model of a market-based determination of the concession value assumes competition between the potential concessionaires, various sizes of investment inputs and costs, and varied productivity. In this respect, the percentage structure in Figure 1 could change to the benefit of an increased share of the grantor and a decrease in the cost share. Such market-based granting of concessions would have a positive effect on the economic growth. The same effect may be achieved through economic exploitation of natural goods which would appear on the market for the first time and would start to be valorized. 5. CONCLUSION Countries in transition will have to develop mechanisms to adjust the economic development to the (natural) environmental protection and to abolish the consequences of the preestablished environmental damage. Concession granting to natural goods is one possible way. The market-based determination of the payment to be made for a concession on the basis of ownership to natural goods should include the valorization of natural goods as a value element which takes place on a tourist market in the form of a higher price of products and services due to a higher tourist demand whose reason and cause is the presence of natural attractions. In countries in transition, where the natural goods have been valorized indirectly on the market, introduction of repayment concessions on the basis of priority and exclusive rights to concession granting to the present real estate quasi owner, would improve protection and maintenance of the natural environment. As far as natural goods are concerned, a market model of granting concessions through a public tender or auction would enable a more efficient economic exploitation of resources and capital. It would also connect the management of the environment with the economic growth. Introduction of a rent (also in form of an anticipated environmental rent) on the basis of a different category of environmental quality, would encourage investments in environmental quality, speed up the structural changes and increase the valorization value of natural goods and the rate of economic growth. REFERENCES Adam J.H. (1990): Dictionary of Business English. - Essex, Longman York Press. Becheri E (1990): Rimini and Co. - the end of a legend? Dealing with the algae affect. - Tourism Management, Vol. 11, No. 3, p.229-235. Collin P.H. (1986): English Business Dictionary. - Beccles, William Clowes. Dekleva J. et all. (1993): Zemljiška politika kot inštrument izvajanja prostorskih planov. Faza I: lastninjenje zemljišč. - Ljubljana, Urbanistični inštitut Republike Slovenije. The Environmental Protection Act (1993). - Ljubljana, Ministry of the Environment and Regional Planning. 12 Frost F. (1993): Greening and Growing - The Role of Government. - Journal of General Management, Vol. 18, No. 4, p. 57-78. Gabler Wirtschafts-Lexikon (1988). - Wiesbaden, Gabler Verlag. Grilc P., Juhart M. (1991).: Koncesijsko razmerje in koncesijska podgodba. - Pravnik revija za pravno teorijo in prakso, Vol. 46, No. 1-2, p.13-27. Humboldt-Wirtschafts-Lexikon (1988). - München, Humboldt-Taschenbuchverlag Jacobi KG. Kovačič A. (1994): Novi predpisi v praksi. - Pravna praksa, No. 15, p. 7. Kovačič A. (1996): Koncesije na vodah. - Koncesije na naravnih dobrinah. Gradivo za posvet. Ljubljana, Institut za pravo, GIZ gozdarstva Slovenije, p. 37-43. Mihalič T. (1995): Ekonomija okolja v turizmu. - Ljubljana, Zbirka EF Maksime. Pauly T. (1996): Pacific Northwest Regional Report. - Internet, March, 7th. Popov D. (1991): Neka aktuelna pitanja razvoja koncesija prirodnog bogastva i dobara u opštoj upotrebi. - Privredno pravni priručnik, No. 1-2, p.3-10. Samuelson P. A., Nordhaus W.D. (1985): Economics. - New York, McGraw-Hill, Inc. Sotto H. (1993): The missing ingredient. - The Economist, 11.9.1993, p. 8-10. Tschurtschenthaler P., et all (1981): Die Berücksichtigung externer Effekte in der Fremdenverkehrswirtschaft. - Jahrbuch für Fremdenverkehr 28/29, p. 93-135. Yosemite News (1996). - Internet, March, 13th. Velkaverh G. (1996): Koncesije na morskem dobru. - Ljubljana, Institut za pravo, p. 23-35. Wahrig G. (1991): Deutsches Wörterbuch. - München, Bertelsmann Lexikon Verlag. Woll A. (1991): Wirtschaftslexikon. - München, R. Oldenbourg Verlag. Zakon o gospodarskih javnih službah (1993). - Ljubljana, Uradni list Republike Slovenije, No. 32. Zakon o spremembah in dopolnitvah Zakona o varstvu okolja (1996). - Ljubljana, Uradni list Republike Slovenije, No. 1. Zakon o zavodih (1991): Ljubljana, Uradni list Republike Slovenije, No. 12. 13 APENDIX Figure A1: Natural Goods NATURAL GOODS STOCK AND FLOW NATURAL ELEMENTS Renewable NATURAL Non-renewable ELEMENTSATURAL Concessions for: RESOURCES – economic exploitation NON-EXPENDABLE NATURAL RESOURCES NATURAL NATIONAL ASSET Concessions for: – management – use Concessions for: – management – use - economic exploitation Source: The Environmental Protection Act, 1993, Art. 5, 17 and 21. 14