Handbook for student accommodation providers

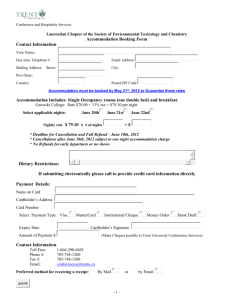

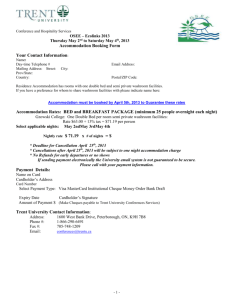

advertisement