Towards Best Practice in Provision of Transport Services

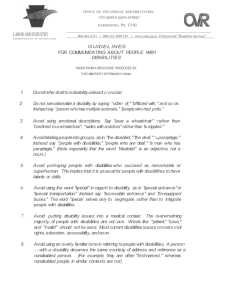

advertisement