lesson 5 - john p birchall

advertisement

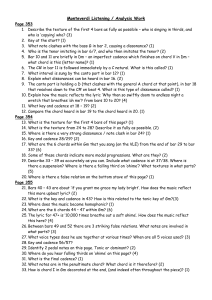

LESSON 5. INTERESTING SOUND TRAJECTORIES. 5.1 Harmony The added 6th chord. In describing chords we have previously noted the relationship of an individual pitch to a root. We say that a note is a 3rd, a 5th or a 7th away from the fundamental note. Therefore to construct an added sixth chord, we start with the major chard and add to it a note which is a 6th from the root. See Ex.1 for a complete list. Note that this is the first chard we have met which is NOT BUILT BY ADDING THIRDS. Since there are 4 notes in the chord there will be 4 close positions or inversions. For the time being we shall use the 6th chord on I and IV of the scale only. The general terminology will be 16 and IV6. In the key of C, the chords will be C6 and F6. You should note the AURAL EFFECT of 6th chords. A certain VAGUENESS occurs when the notes are sounded together, with a fairly high density, but the sound has a DEFINITE RESEMBLANCE to the triad on which it is built, and the 6th is an often used note of the major scale. 5.2 Chord Progressions Basic patterns, 'they all go the same old way'. No new progressions are presented in this lesson but C6 and F6 can be used in place of the C and F triads, that is, as SUBSTITUTES. See Ex.2. We should now note an important principle. Chords may be embellished and substituted to add INTEREST and avoid MONOTONY but the basic pattern of chard movement to and from the sound centre and the basic tendency to move down a 5th remain fundamental. Bearing this in mind it becomes important to ANALYSE the chord progressions of songs to establish the BASIC PATTERN. Progressions which are full of substitutes and look 'complicated' will almost invariably be found to be developments of the basics. The basic pattern will be found to be various permutations and various timings of movements down to the subdominant a fifth below or movements up to the dominant followed by resolutions back to the tonic. Bear in mind that the movement 'down' to the subdominant will often manifest itself as note movement UP. In C, the E goes to F and the G goes to A as suggested in 1.5. Similarly the movement 'up' to the dominant will involve note movements DOWN as E goes to D and C goes to B. These fundamental 'swings' of harmony will easily be found in your songs if you simplify the progression by ignoring substitutions and 'passing chords' and remember you can jump to the dominant's dominant as an added bonus! See 2.1. We will be pursuing more variations on this basic pattern as the course progresses; particularly jumping to the dominant's dominant's dominant!! See lesson 8.2. These BASIC patterns are important for the improviser because it is almost impossible to memorise complex progressions and yet the improviser must know his whereabouts in the song if he is to avoid – dissonant note clashes 'GETTING LOST'. Losing your way in a song is a very common initial problem for improvisers. How can we avoid it? Here are a few tips – NEVER try to count bars, you have no chance! develop the rhythmic 'time FEEL' for the four bar sections as outlined in the last lesson establish the structure of the song. This will usually be 8, 16 or 32 bar popular song format or a 12 bar blues. The structures could have introductions, link sections and tags or an added 4 bar section but the patterns of these songs are usually similar. They tend to be structured around four bar sections as we saw in lesson 2.3. Thus, a good way to start analysis is to look for the EXCEPTIONS, what makes this song dilferent7 establish the BASIC chord sequence, remember 'they all go the same sort of way' so the trick is to learn the way they go! This course is all about learning how the progressions go, they follow the same basic principles. Remember your improvisation will be following the same pattern as the chords, you will be establishing a sound centre, moving away from it, and then returning back to it. Establish WHERE these basic movements occur, establish the basic 'harmonic rhythm'. See 2.2. look for the important CADENCES which conclude the 4 and 8 bar sections. Remember progressions are like a journey to a cadence point. See 2.1. Make familiarity with these cadences your first TARGET. IGNORE any fast changes of less than, at least, the half bar, you will never play them anyway! ignore all substitutes and passing chords which don't affect the basic sound. we should stress that although you need to know the key and the sound of the tonic, or 'home base', do remember that the sound changes (the key changes) within the song. Thus the sequence of the chords is far more relevant than the key signature. In summary, it is the progressions of the chords and the 'four bar time feel' which will eventually guide you through the song. Thus, you need to analyse the chord progression and simplify it into the basic sound, establishing where the sound changes as the chord changes. This then becomes a 'landmark' which eventually you will recognise. See lessons 2 and 3.1. All this sounds like a 'cap out' - we seem to be saying 'don't worry you wilt learn how to avoid getting lost by experience'! Although this is perfectly true we do want to stress the importance of STUDYING the song structure and chord progression and PRACTISING those 'four bar time feels'. We have said that it is perfectly possible to learn to improvise by 'ear alone' but it does make life incredibly difficult. The songs you will be playing do follow a pattern, learn the patterns and you have learned thousands of songs. See 5.5 below. Now we must alert you to the fact that – ALL THE MOST INTERESTLNG SONGS BREAK THE RULES! Don't panic! As we suggested above the way to handle this problem is to learn the EXCEPTIONS. Memorising the differences is a lot easier than memorising the totality. 5.3 Melody Experiments & analysis. Ex.3. shows the arpeggiated versions of the 6th chord. Many new patterns now become available in melodic work and Ex.4 to 11 are typical examples. Remember to memorise these exercises as a preliminary to their use as improvised material. The patterns in Ex.3 should also be transposed onto all the chords shown in Ex.1. In addition to memorising and transposing the exercises, which has been mentioned repeatedly, practice should always involve EXPERIMENTS. Remember lesson 3.6 and the importance of initiative. For example, with these exercises try experimenting with – staccato and legato phrasing. Various combinations of smooth and attacked phrasing should be tried. The same notes can produce entirely different effects, The choice of staccato or legato phrasing provides additional grist for the mill. accents. Try various forms of accentuation. With the distribution of a chord in 4 eighth notes, accent the quavers in turn and listen to the effect. Try different combinations of accents. speed. Listen to the effect of different speeds. Too slow and all sense of swing and motion can be lost. Too fast and the piece can become devoid of all rhythmic feel. However, the exercises should never be played faster than current technique allows. In general, exercises should be commenced quite slowly, gradually working up to double tempo versions. See Ex.12. Then choose the tempo which gives the piece the best swing or feel. swing. Above all experiment with the TIMING of the notes to get a better 'swing'. It is very difficult to appreciate swing when you are practising alone. The best advice is to work with a metronome and tape your efforts so that you can critically listen to the effect and subsequently experiment with different timings. At this stage, a full ANALYSIS should be made of all exercises and experiments, using Ex.13 as a model. The purpose of this is to draw attention to the various processes, 'rules' and principles involved so that they become prominent in the consciousness. Refer back to 2.4, 3.4 and 4.5, 5.4 Rhythm Staying off the heat & phrase continuity. More bar patterns are shown in Ex.14. These exercises introduce you to rhythms which 'stay off the beat' as a succession of off beat notes are presented. The easy syncopation we met in lessons 3 and 4 where the beat returned 'home' immediately after the syncopation is now extended into further off beat patterns, thus prolonging the tension and creating a different effect. Analyse these patterns and look for the repeated off beats or 'bahs'. We have marked some of them for you. Don't forget the off beats are attacked notes which are hit with the foot off the floor at the top of its movement. Get used to the 'feel' of these rhythms. They should be studied, memorised and practised in the way we outlined in the last lesson 4.4. Remember the rhythmic components we need to manipulate will only become dominant in your memory through conscious attention, and constant practice. As suggested previously, PHRASE BULLDING involves arranging rhythmic patterns or continuities, to form phrases by repetition or combining, recombining or displacement of these and similar bar patterns. When you improvise you will be recreating SOUND PATTERNS from material embedded in your memory. You will 'hear' the overall pattern of sound, not the individual notes. In the same way the sight reader, when reading music, recognises familiar SHAPES of groups of notes and not the individual notes. Phrase building whether simple or complex, whether by repetition, combination, recombination or displacement must result in CONTINUITY. Throughout this course we have used the word 'continuity' to describe improvised melodies and we think it is a MEANINGFUL WORD. When playing melodies in the rhythmic jazz idiom, FORWARD MOMENTUM is essential if the rhythms are going to swing. Jerky discontinuities will destroy swing and rhythmic impetus. When phrase building you should attempt to – LAUNCH INTO A 4 BAR TRAJECTORY!! This descriptive phrase should sum up the focus of your efforts, it involves thinking ahead and avoiding discontinuities in melody when chords change. Try to think of 4 bar phrases as a smooth flight to a cadence. The sign of a good developing jazz improviser is one who makes the 'changes' during the 'journey' sound smooth and natural. This will not be easy initially because as we play we will be 'looking' for the chord changes and consciously moving to a different combination of finger patterns and notes, however with time and practice and by employing the smooth note changes outlined in lesson 1.5, our fluency and FLOW OF UNINTERRUPTED MELODY should improve. Continuity is about achieving a natural rhythm and swing. We strongly believe that this essential rhythm and swing is extremely difficult if not impossible to learn and practice in isolation on your own. We mentioned in lesson 2 the importance of practice with a metronome, we now stress the importance of practising with a rhythm section. This is not only to keep TIME and hear chord CHANGES but also because of the essential characteristic of SWING which is the 'juxtaposition' of rhythmic lines. A firm satisfying foundation is essential to support ail improvised melody lines. We suggest that jazz swing is the result of superimposing rhythmic complexity over a basic ground beat. You cannot launch into a swinging melodic trajectory without a groundbeat benchmark! See later in lesson 11.4. We have already mentioned the problem of consistent time keeping when playing by yourself but there is also another potential pitfall we mentioned in lesson 4.2. This is the temptation to play too many notes. Without a rhythm section you will tend to keep playing 'to keep the beat going', but the art of relaxed swing is to place notes in the right place and when you are learning this is best done by not rushing, by silences or rests, which can be just as effective as notes - if they are in the right place! After 1918 early jazzmen learned by 'playing along' with records. This is an excellent way of progressing providing the problems of tuning can be overcome. Recordings and record players do not always play at a consistent speed and therefore pitch. A further problem when playing with records is 'space'. it is likely that your own playing will clash with instrumentalists on the record. Luckily there, are ways round these problems. Special practice accompaniment records can be purchased or tapes of backing instruments can be made. The tape recorder is a boon for practice. But best of all you can practice with others. Whichever way you choose to practice remember that jazz is a COLLECTIVE music, individual contributions are often meaningless without the context of the group. See 5.6. below. It can be argued that these remarks don't apply to the pianist who can provide his own rhythm section, but even for the piano it is easy to loose timing and swing when playing in isolation. 5.5 Memory Pattern recognition. Lessons 2.4, 3.4 and 4.5 covered the establishing of patterns in the brain. But after all the hard work and practice no doubt you will worry about whether you will actually REMEMBER when you came to perform! Is it really subconscious? This is a big concern for most of us, we have learned the vocabulary, the grammar and the idioms but how do you remember them!? Is mere repetition the only requirement for successful memorising? The answer is that we can in fact 'help' our subconscious 'memory'. All honest jazzmen will tell you that there are some days when their subconscious does not produce the goods and they all must have something to fall back on. They do in fact fall back on their memory but even here careful study can help. Learning such a mass of material 'parrot like' is undoubtedly the hard way! This course hopes to alleviate the burden on memory by making you conscious of the 'rules' which underpin the 'correct' sounds. The leaning process involves ESTABLISHING patterns in the brain. Memory is very much connected with the RECOGNITION of those previously experienced patterns. Music is not a random process, but neither is it predictably orderly. However, it does have patterns which can be recognised. Take the following series of numbers – 2 5 3 7 4 9 5 11 6 13 7 15 8 17 9 19 10 21 11 23 12 25 13 27 The memorising of this number series would be very difficult if no relationship existed between the numbers. However, when we spot that the series splits into 2 sets, each of which has its own pattern of increase, it is very easy to commit to memory. Alternate numbers. Set 1 increases by 1 – 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Set 2 increases by 2 – 5 7 9 1113 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 If we now remember that the starting point of set 1 is 2 and the starting point of set 2 is 5, and that the series makes 12 changes, we could reproduce the set at any time. We could also CONTINUE the set, or MAKE UP OTHERS by using the same principles. Let us take Ex.8 of this lesson and subject it to the same kind of analysis – pitch – a series of adjacent inversions of the chord with an appoggiatura before each inversion time – a continuous succession of quavers with 1 long note at the end. It is not difficult for us to see that this method of memorising is much more efficient than the alternative of trying to commit to memory a series of individual notes. You should note that we are using similar principles in the construction of the material for this course – harmony melody rhythm is memorised in terms of PROGRESSION 'rules' is memorised in terms of CHORDS and their inversions, DECORATED by various unessential notes, which again conform to 'rules'. is memorised in terms of 'typical' BAR PATTERNS Thus, another important principle emerges – ONCE THE RULES ARE UNDERSTOOD YOU WILL BE AMAZED AT THE AMOUNT OF MATERIAL THAT CAN BE MEMORISED. This is the real advantage of learning improvisation by the methods outlined here. As we have said, no doubt you could progress purely by 'ear' but the task and memory requirements are enormous. Assimilate the 'rules' and 'patterns' and vast quantities of material will fall into place and be available for recall. You have no trouble recognising hundreds of faces of people you know why should you have trouble remembering hundreds of songs? Thus when you are improvising think – PICTURES, SHAPES, IMAGES, VISUALISATIONS, ARRANGEMENTS, DIAGRAMS, PLANS, SKETCHES … … Anything to help form a – MENTAL PATTERN Ex.15 and 16 are two more examples of 8 bar continuities for practice of co-ordination of rhythm, harmony and melody. They include the progression and chord decoration 'rules' that we have discussed and are set to a syncopated rhythmic continuity. Ivan Huke, a friend and blogger from Nottingham, has thought long and hard about memory and how our repertoire involves songs which ‘all go the same old way’. His notes are ‘Chord Progressions’ are well worth reading and are Appended. 5.6 Playing Together Have a go. However enthusiastic you are your progress will improve rapidly if you play with other people. In the same way as attempting free improvisation it is never too early to start playing with others. We have already mentioned that jazz is a collective social music and that you will learn from your colleagues and you will also have more fun. The first thing to note about playing with others is that it is MORE DIFFICULT than playing on your own! However familiar you think you are with the material to be played you will be surprised by the playing of others. Others will have DIFFERENT approaches to timing, rhythm and 'interpretation' or 'mood'. Thus, it is important that your own pre session practice should be thorough so that you are not preoccupied with finding the chord sequence or melody notes and you are free to concentrate on the new issues which will only arise when you start group playing, Once you have smoothed out the tempo and interpretation differences the target of your effort should be to establish a COMPLEMENTARY contribution. Remember this is an improvisation course so we are not concerned with written parts. Think of your playing as one part in a part playing 'round'; think of playing a HORIZONTAL SEBUENCE which is rhythmically interesting which when COMBINED with the others produces a VERTICAL HARMONY consistent with the chord sequence of the song. You, collectively, are trying to produce a COHESIVE total sound so you must play the 'right' notes at the right time. You must play within the RULES of the idiom. 'Complementary' contributions are produced essentially by 'balanced' playing of independent melodic lines over the same chord sequence with each instrument contributing a 'counterpoint' or 'contrary motion' part. Apart from expertly dodging 'bum notes', clashes are avoided by playing – in different registers, traditionally the trumpet will play in the middle, the clarinet in the higher register and the trombone in the bass different note lengths, this can be achieved by the trumpet playing quarter notes the clarinet eighth and the trombone half notes at different times, this is usually a case of 'leads' and 'fill ins' or 'calls' and 'responses'. The TRADITIONAL instrumental roles can be summarised as follows but instead of starting with the lead trumpet Ex.17 or clarinet Ex. 18 of trombone Ex 19 we start with the drums and rhythm section and build up from a foundation ... NATURAL and SPONTANEOUS and PERSONAL and FUN – the drums provide time keeping and 'ride' rhythm variations; these rhythms not only help to keep time but also break up the four to the bar regularity and 'propel' the performance, contributing to the jazz feeling and swing. However the vital role of the drummer is to lay down the GROUND BEAT against which the other instruments play. Ex.21. shows some typical ride rhythms. The first drum rhythm in jazz in 4/4 time distinguishes between the 1 and 3 down beats and the 3 and 4 off beats, perhaps with the bass drum on 1 and 3 and the snare or cymbal on 3 and 4. Not 1 – 2 – 3 – 4 but bom – chick – bom – chick, as the cymbal ‘answers’ the bass drum. In this way the rhythm ‘lifts’ and ‘bounces’ along. The rhythm is ‘skipped’ as if dancing. We will discuss drumming again in later lessons. the bass plays an ostinato ‘four to the bar' continuity, 'walking' figures provide timing, notes emphasising the chord sequence and continuity which keeps the forward momentum going. See Ex.20. The bass plays big notes, slowly and leaves space for others. Sewing a ‘bass line’ into the drum rhythm. the banjo adds to the rhythm and plays 'four to the bar' chords, down strums on the beat, up strums off the beat and other rhythmic subtleties, again the impression is of an underlying basic pulse with a superimposed variation. The three together, mixing it up and feeling the cohesive beat, flexible but firm at the same time. the rhythm section establishes the ground beat, a basic 'four to the bar' sometimes with 'riffs', or repeated rhythmic patterns, which are constantly 'broken up' by the lead instruments but establish a groove. the lead comet or trumpet plays a syncopated pulse, essentially pentatonic trajectories, attack tonguing the up beat and 'kicking' the quavers! See Ex.17. The cornet is firm and strong, on the melody, but with a swinging lilt. Play with the rhythm, it has to be fun. the clarinet plays a 'weaving' melody, with plenty of fills, trills, arpeggios, passing notes and appoggiaturas. See Ex.18. The clarinet is differentiated as high and fast. the trombone emphasises the harmonic 'changes' and also plays 'fills'. See Ex.19. note the trombone part is usually written on the bass clef. The trombone can slide up to chord notes and place them in context for others hear and respond to. The trombone is differentiated as low and slow. the piano plays the chords and accompanies the melody, often by syncopated 'comping', with the chords broken up in a variety of voicings and complementary rhythms. These traditional roles have developed continuously over the last century as jazz has evolved into more complex forms, although many of the basics remain the same. A significant development followed an increase in the size of bands. 'Collective' improvisation is difficult once there are more than three instruments in the front line and written arrangements for instrument 'sections' becomes necessary. See lesson 7.6 and the jazz tradition. Whatever approach is adopted for the sharing of roles the golden rule is to avoid any tendency to 'stereotype' or 'mechanical’ playing. You must never 'take turns' or stick to any established pattern, jazz must sound NATURAL and SPONTANEOUS and PERSONAL and FUN. After inhibition and lack of confidence we suggest the most common failure when first attempting group playing is a tendency to be SELFISH. The objective is not to show off your latest wizardry on your instrument, it is an opportunity to make the playing of others sound better. But what is the best way of proceeding? Here is a suggested check list – if you are all of a similar ability so much the better for 'harmony' and fun but someone has to ensure a reasonable discipline! discipline involves not only the obvious about deciding what is to be played, for how long, in what key, at what tempo and with what structure of song form, breaks and soloists, but also about when to stop and 'sort out' as against when it is more fruitful to continue the flow the group should acquire or assemble 'LEAD SHEETS' for the songs they play thus ensuring everyone is 'singing from the same' unless there is a specific reason, the compass of a singer is the most obvious, always play in the 'WRITTEN' key, and always play to the 'written' chord sequence. This is not so much out of 'courtesy' to the composer but also helpful in that everyone practices the same way and 'sitting in' with others is easier before starting the Bb and Eb instrumentalist must ensure they have TRANSPOSED all lead sheets into their keys TUNE UP before you start it is almost impossible to start playing in a group without a TIMEKEEPER. This is normally the drummer, but in small groups it could be the banjo or guitar player, or less satisfactorily the piano or keyboard players left hand the banjo and, particularly, the piano player must 'lay down' the CHORD SEQUENCE. This should be quite forthright initially, it is vital for everyone to hear the chords a LEAD player is also appropriate to establish the tempo and delineate the melody. This role is usually assigned to a trumpet start with SIMPLE songs, don't try to run before you can walk, 12 bar blues and three chord spirituals? choose keys and tempos that are MANAGEABLE but do not hold back from experiment playing ONE SONG for an hour is better than one every 5 minutes, you must try to work out the bugs as you go along, don't expect to be flawless throughout playing one note in the RIGHT PLACE is the target don't worry about silences. In fact deliberately try to leave plenty of gaps which will encourage the others to ‘fill in’ introductions and endings have to be organised, somebody must COUNT IN or play and intro. and endings have to be AGREED, endings are undoubtedly the most difficult the most common problems to start with are POOR TIME KEEPING and GETTING LOST, expect them. In the case of a group, playing with a metronome is useless; it can't be heard, it confuses and gets in the way, exactly the reverse of when you are playing on your own. You must rely on your appointed timekeeper. When you get lost stop and listen to the others, don't be selfish and assume that it is the others that are wrong or that they will join you! listen to the others and TRY to avoid clashes avoid all criticism and INHIBITION, go for it! Remember you are trying to create interesting sound trajectories as COMPLEMENTS, it is the COLLECTIVE sound that is important. 5.7 Written Work. Write an 8 bar continuity of melody, harmony and rhythm based on the material supplied up to lesson 5. Do a complete breakdown of all of the three musical components. NB. Don't get DISHEARTENED! Most students try to move ahead too quickly. While we applaud enthusiasm we must point out that progress depends on accumulating steadily. There are two elements in this last lesson, 'getting lost' and attempting to 'launch into an interesting sound trajectory', WITHOUT CLASHING WITH OTHERS, which will almost certainly cause you some frustration. DON'T WORRY the more you work the better will be your 'bearings' and your 'continuities'. John p birchall website = http//:www.themeister.co.uk Chord Progressions by Ivan Huke 1. THE RED ROSES PROGRESSION Definition: Tune begins on the tonic (usually two bars) and then moves on to the 7th (also usually two bars), meaning that in the Key of F the first chord would be F major and the next E major (or E7th). Note: Rare but effective. Examples: Blue Turning Grey Over You Sweet Emmalina Cherry 'Taint No Sin to Take Off Your Skin Dream When Somebody Thinks You're Wonderful Mister Sandman Sweet Substitute Red Roses For A Blue Lady Whispering Home (When Shadows Fall) You Won't Find Another Fool Like Me Is It True What They Say About Dixie? The Curse of an Aching Heart Some Day You’ll Be Sorry Need a Little Sugar in My Bowl (in half-bars) 2. THE SALTY DOG PROGRESSION Definition: The tune begins (usually two bars) on the chord of the 6th note in the scale (e.g., a tune in the key of G starting on the chord of E or E7th). This is normally followed by the chord on the 2nd note of the scale, and then on the 5th note of the scale, thus continuing the ‘circle of fifths’. Note: Rare, but effective. Clever use of the ‘circle of fifths’. Examples A Good Man Is Hard To Find Rose of the Rio Grande Alabamy Bound Salty Dog [the archetypal tune of this kind] Any Time Seems Like Old Times At The Jazz Band Ball [main strain] Shine On Harvest Moon Balling The Jack Sweet Georgia Brown Friends and Neighbours Tailgate Ramble Good Time Flat Blues (also known as Farewell to There’ll Be Some Changes Made Storyville) [chorus] Up A Lazy River Jazz Me Blues [main strain] You've Got The Right Key But The Wrong Keyhole Louis-i-a-ni-a 3. THE GEORGIA PROGRESSION Definition: The tune starts on the tonic, proceeding to the chord of the 3rd and then on to the 6th. So in the key of C, this would mean C major, followed by E7th and then A7th (sometimes A minor). Note: Very common. Especially popular in 1920s. Frequent in Charleston-style tunes; but also works well in slower numbers. Examples All of Me I'm Alone Because I Love You Barefoot Boy It’s Only A Shanty Basin Street Blues[main theme] I've Heard That Song Before Black Bottom Stomp [introduction] Lover Come Back To Me Charleston Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone Clarinet Marmalade [main theme] Taint Nobody's Business If I Do Darkness On The Delta That Da-Da Strain [second theme] Do Your Duty Whenever You're Lonesome Georgia We’ll Meet Again Give It Up Who’s Sorry Now Has Anybody Seen My Girl? You're Nobody Till Somebody Loves You If You Were The Only Girl In The World 4. THE SWEET SUE PROGRESSION Definition: Begins on the Dominant 7th, with the Tonic as the next chord. (Often this pattern is then repeated before further developments.) To put it simply, if you’re in the key of C, you begin these tunes on G7th (usually two bars) and then move on to C. Note: Very useful when composers fancy bouncing back and forth between the dominant and the tonic. Simple and therefore popular with improvisers. Examples April Showers Sailing Down the Chesapeake Bay Auf Wiedersehen Say Si Si Avalon Says My Heart Black Bottom Stomp [final strain] Smiles Dallas Rag Smokey Mokes (main improvising theme) Do What Ory Say So Do I Gatemouth South [second strain] Heebie Jeebies Sweet Sue His Eye Is On The Sparrow That’s A Plenty [final strain] I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate Tom Cat Blues Jealous Up Jumped the Devil Louisiana Way Down Yonder In New Orleans Memphis Blues (Verse) We Just Couldn't Say Goodbye Miss Annabelle Lee Willy The Weeper [second strain] My Life Will Be Sweeter Some Day Winin’ Boy Blues Papa De-Da-Da (chorus) You Were Meant For Me Pretty Baby 5. THE BYE BYE PROGRESSION Definition: Begins on the tonic. This is followed by the 6th flat major, then tonic again, and then 6th. So in the key of C this would be: C - Ab - C - A. Note: It is rare - a pity, because it has a lovely effect when a composer wants to inject something wistful very early on in the tune. Examples Bye Bye Blues Oriental Strut (main theme) Out Of Nowhere San 6. THE MAGNOLIA PROGRESSION Definition: The tune starts on the Tonic, then moves to the Tonic 7th; then the chord of the 4th note in the scale; and then the 4th minor (or sometimes diminished). So, in the Key of C, this would mean: C : C7 : F : Fm Notes: It's known as The Magnolia Progression because it was used to begin the chorus of the famous 1928 Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields jazz tune Magnolia's Wedding Day. It is a super progression and deservedly popular. It is so natural and logical. The listener really feels the harmonies, so it’s well suited to emotional ballads such as My Mother’s Eyes. But it also works with up-tempo numbers. Examples After My Laughter Came Tears In the Upper Garden Big Boat I Want a Little Girl to Call My Own Brown Skin Mamma Lonesome Road Carolina Moon Louisiana Fairytale Cherry Red Magnolia's Wedding Day 'Deed I Do My Mother's Eyes Does Jesus Care? Old Rocking Chair Girl of My Dreams Rock Me If I Had You Rolling Round the World I May Be Wrong But I Think You're Wonderful Stevedore Stomp [final strain] I'm Gonna Meet My Sweetie Now When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano I'm Putting All My Eggs in One Basket 7. THE MY OLD MAN PROGRESSION Definition: The tune starts on the Tonic chord and then follows this with the commonest chord progression of all - known to musicians as 2 - 5 - 1. So a tune beginning on the chord of C major, for example, would progress on to D major (the chord of the second note of the scale), followed by the chord of G7th (the dominant seventh - the fifth note of the scale) before returning to C major. A very satisfying 8-bar musical phrase can be built on two bars each of these four chords. Notes: Exceptionally simple. Very popular in the early part of the Twentieth Century. This is known to musicians as The My Old Man Progression because it is the basis of that song of the music hall era, My Old Man Said Follow The Van. Examples Ain’t Gonna Give Nobody None Of My Jelly Roll I Like Bananas Because They Have No Bones All By Myself in the Morning I’m Looking Over A Four-Leaf Clover Big Chief Battleaxe (Main Theme) I'm Nobody's Baby Button Up Your Overcoat Kiss Me Sweet By the Light of the Silvery Moon Lulu's Back in Town [follows the pattern in half-bars] Congratulations Ma, He's Making Eyes At Me Darktown Strutters Ball Memories Destination Moon My Cutie's Due at Two to Two Don’t Sweetheart Me Oh, You Beautiful Doll Down In Honky Tonk Town [with four bars on each of the On Treasure Island chords] Peg o' My Heart Down In Jungle Town Put on Your Old Grey Bonnet [the verse, not the refrain] Exactly Like You Red Hot Mamma I Can't Escape Somebody Else Is Taking My Place I Double Dare You Toot Toot Tootsie If You Were The Only Girl In The World Underneath the Arches Jersey Bounce Ory’s Creole Trombone [main theme] You Made Me Love You 8. THE DRAGON PROGRESSION Definition: The tune starts on the chord of the Tonic and then follows this with the minor chord on the third note of the scale. Note: My friend John Burns taught me this one. Thanks, John. It is simple but distinctive. Just think of the openings of the tunes listed and you will see what I mean. Examples Home in Pasadena [chorus] Happy Days and Lonely Nights I'm Gonna Sit Right Down and Write Myself a Letter The White Cliffs of Dover In Apple Blossom Time When You’re Smiling Puff, the Magic Dragon You Always Hurt The One You Love 9. THE SAINTS PROGRESSION Notes: Everybody knows When the Saints. Its progression is instantly recognisable and fairly simple. But, as far as I know, it has not been widely used. Definition: Starts with (what could be easier?) six bars on the Tonic chord. Then briefly the Dominant 7th. Then it uses the Magnolia progression (see above). Examples Livin' High (Chorus) Reefer Man When then Saints Go Marching In Will You Sleep in My Arms Tonight, Lady? I'll Be Glad When You're Dead, You Rascal You We Shall Walk Through The Gates Of The City Peruna Who Threw the Whisky in the Well? (Chorus) Red River Valley 10. THE APPLE TREE PROGRESSION Definition: Start on the chord of the Tonic; then move on to the chord of the 4th note of the scale; and then back to the Tonic. So in the key of C, the first three chords would be C - F - C. Notes: Very common. Gently rocks you away from the tonic and back on to it. Examples After the Ball is Over Precious Lord, Lead Me On Amazing Grace Red Sails In The Sunset Blame It On The Blues [main theme] Salutation March [main theme] Bugle Boy March [main theme] Sometimes My Burden Is Too Hard To Bear Delia's Gone The Rose Room Gettysburg March Wait Till The Sun Shines, Nellie I Love You Because Walking With the King I'm Sitting On Top Of The World Way Down Upon The Swanee River (aka The Old Folks At In The Sweet By and By Home) I Wish'T I Was in Peoria Walking the Dog Lady Be Good What A Friend We Have In Jesus Marching Through Georgia When You And I Were Young, Maggie My Gal Sal Redwing My Old Kentucky Home Yearning Poor Old Joe 11. THE LOVE MY BABY PROGRESSION Definition: Begin with 4 bars on the Dominant 7th and then 4 bars on the sixth note of the scale. To put it simply, if you play the tune in the key of G, the first 4 bars will be on D7th and the next 4 on E7th. Notes: Surely it can’t be unique to I Love My Baby? It seems like an unremarkable pattern and yet I have found only this one tune that uses this catchy sequence. Example I Love My Baby 12. THE BILL BAILEY PROGRESSION Definition: First six bars on the Tonic, next eight on the Dominant 7th. Next two on the Tonic. Start second sixteen on the Tonic, etc. End 4 – 4 minor – 1 – 6 seventh – 2 seventh – 5 seventh – 1 - 1. The tunes listed below do not all stick to it 100%, but they do so as nearly as makes little difference. Notes: For 32-bar tunes, this is probably the best-known progression of all, very easy to improvise on. It is possible for jazzbands to 'invent' tunes on the spot, using this progression - I have witnessed several doing just that. Examples Amapola (for the first 24 bars) Knee Drops At The Mardi Gras Merci Beaucoup Baby Face Milenburg Joys (main theme) Beer Barrel Polka[main theme] My Little Girl Bourbon Street Parade Over The Waves Don't Give Up the Ship Second Line Ciri Ciri Bin Spanish Eyes (almost all) Golden Leaf Strut Tiger Rag (final strain) Hiawatha Rag (final strain) Tulane Swing Hotter Than That Won’t You Come Home, Bill Bailey? 13. THE TWELVE-BAR BLUES PROGRESSION Definition: Twelve bars, essentially: 1 1 1 17th 4 4 1 1 5 7th 5 7th 1 1 Variations within that pattern are encouraged. Notes: The basis of so much jazz, not to mention Rock 'n' Roll. Examples Beale Street Blues St. Louis Blues .......in fact all the 12-bar Blues! ..........and note (interesting) that The Girls Go Crazy and The Bucket's Got a Hole in It use just the final eight bars of the 12-bar Blues Pattern. 14. THE SUNSHINE PROGRESSION This eight-bar progression got its name from the late, great British clarinet player Monty Sunshine. Definition: In the Key of C, the eight bars would be: F major F minor C major A7 D7 (or D minor) G7 C major C major In other words: Chord on the 4th of the scale Chord on the 4th Minor (or diminished) Chord on the Tonic Chord on the 6th seventh Chord on the 2nd seventh Chord on the 5th seventh Major Chord on the Tonic Major Chord on the Tonic Notes: This sequence makes the most familiar (and often rousing) finale to so dozens of tunes; but - interestingly - it is also used at the BEGINNING of a few tunes. Examples of THE SUNSHINE SEQUENCE at the BEGINNINGS of tunes: After You’ve Gone Strut Miss Lizzie Glad Rag Doll That’s My Home I Can’t Believe That You’re in Love With Me Examples of THE SUNSHINE SEQUENCE at the END of tunes: All of Me It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie Amapola It’s Only a Shanty April Showers June Night At the Jazzband Ball (second theme) Knee Drops Baby Face Merci Beaucoup Beer Barrel Polka [main theme] Milenberg Joys Beneath Hawaiian Skies Mobile Stomp Bill Bailey My Little Girl Blame it on the Blues [final theme] Over the Waves Bourbon Street Parade Riverboat Shuffle Bugle Boy March [main strain] Running Wild Call Out March Salutation March China Town Shine Ciri Ciri Bin Slow Boat to China Frogimore Rag [main strain] Somebody Else is taking My Place From Monday On Spanish Eyes Golden Leaf Strut Struttin' With Some Barbeque Hiawatha Rag [main theme] Tell me Your Dreams I’m Looking Over a Four-Leaf Clover Tiger Rag If I Had a Talking Picture Tulane Swing 15. THE JA DA PROGRESSION Definition: The song begins on the tonic and this is followed by the chord on the 6th note of the scale (generally leading into the circle of fifths). For example, in the Key of C, you would start on the chord of C major, leading in to A7th and then D7th. Examples: It Had To Be You I'm Dreaming of a White Christmas Ja Da If I Had My Way Dear Crazy That's a Plenty [main theme] Porter's Love Song to a Chambermaid If You Don't, I Know Who Will Japanese Sandman Nobody's Sweetheart Now Coney Island Washboard Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland Give It Up Paper Doll The Gypsy Somebody Else is Taking My Place Don't Get Around Much Any More I'm Sorry I Made You Cry Don't Go Away Nobody 16. MINOR KEY PROGRESSIONS Definition: Much of the tune (sometimes just the first part) is in a minor key. Notes: I am surprised there are not more tunes in the traditional jazz repertoire using minor keys. The effect of the minor is striking and unusual. For an obvious example of this, just hum St. James' Infirmary to yourself. Playing an occasional tune in a minor key gives variety to a concert programme. To improvise on it, you have to make a mental adjustment and 'think minor'. Examples: At the Jazz Band Ball (usually starts in G minor - part A) Bei Mir Bist Du Schoen Big House Blues [final theme] Caravan Crying for the Carolines Dark Eyes (though the opening chord is the dominant seventh - not minor) Egyptian Ella Green Leaves of Summer Hush-a-Bye I'm Humming to Myself I'm the King of the Swingers (part A) Joshua Fit De Battle of Jericho Lotus Blossom Midnight in Moscow Minor Drag New Orleans (the Hoagy Carmichael tune) Petite Fleur Puttin' on the Ritz (Chorus) Satan, Your Kingdom Must Come Down Shout 'Em, Aunt Tillie Sing Sing Sing with a Swing Steppin' Out With My Baby St. James' Infirmary Summertime Sway That Da Da Strain (usually starts in G minor - part A) Tight Like This When I Get Low I Get High Why Don't You Do Right You Let Me Dow