Timothy J

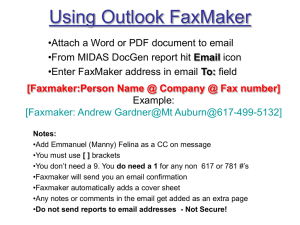

advertisement

Timothy J. O’Brien Buzzanco Fall 2006 Lloyd C. Gardner, Economic Aspects of New Deal Diplomacy. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1964. Lloyd C. Gardner, one of the nation’s leading diplomatic historians, is the Charles and Mary Beard professor emeritus at Rutgers University. He has written at least fifteen books. His colleagues included Walter Lafeber and William Appleman Williams. Gardener’s thesis is that the “New Deal’s approach to foreign policy was as much shaped by older principles and traditions as any initiated by Franklin Roosevelt…” The author breaks down his book into four main sections. First he is concerned with the 1933-34 interregnum when the mainly domestically centered New Deal was used as a way to develop a trade policy. The second part is roughly concerned with the effect of the New Deal foreign polices in Latin America, Asia and Europe from 19331937. Thirdly Gardner writes about the 1937-1941 timeframe when the Axis challenge made a major imprint on American policy makers. The last part deals with the wartime period. The discussions, vacillations and eventual formulation of Roosevelt’s international trade policy was informed by Wilson’s Open Door policies and Hoover’s preferences and opinions on domestic recovery and trade. During the London Economic Conference of 1933 Secretary of State Cordell Hull bullied and pushed western nations to get with the program on adopting liberal trade policies to meet the current world economic crisis. Roosevelt in turn repudiated a stabilization plan put forth at the conference that advocated fixing exchange rates stating that world trade and that sound internal economic systems were more important. Two New Deal programs, the National Recovery Administration (NRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) were designated as primary guides to recovery from the Great Depression. George N. Peek, the first director of the AAA was prescient enough to realize that the state of the world was always changing and that international trade could not be “restored” to some past era when a certain country or another was economically dominant. Peek also realized that the United States could not continue to maintain a near monopoly in production in some manufactured products and commodities because some countries had formulated their own Manifest Destiny policies or goals. The most relevant example given by Gardner is one that resonates strongly and is still relevant today. It concerned the coffee producing nation of Brazil. Gardner quotes Rexford Tugwell who was a member Roosevelt’s “Brain Trust” to illustrate the point, “Coffee has taught the Brazilians the great lesson that nations which depend upon the export of raw materials can never be free.” The entire “free” trade versus fair trade issue is raging worldwide forty-two years after Gardner put that quote in his book. The visibility of the “free” trade question is shown by the protests that erupted at Seattle WTO meetings, CAFTA meetings, IMF meetings and many others. Therefore as Tugwell correctly concluded, “Our problem is to maintain free trade at home within a balanced economy.” More acts that opened and maintained trade were passed by Congress during the 1933 to 1939 period than any other time period in U.S. history bearing in mind that the book was published in 1964. These trade related acts included the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, the Export-Import Bank Act, the Cellar Free Port Act, the Merchant Marine Act, the Civil Aeronautics Act and others. Gardner concludes his monograph by writing that New Deal foreign policy didn’t magically arise from an isolated United States and lead us to become world leaders and neither is New Deal foreign policy a guidebook to plot our future foreign policy decisions.