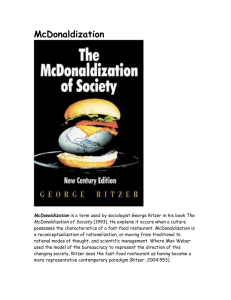

McDonaldization

advertisement

Cecilia Roman Quijas Soc 140 Political Sociology Prof. Jerome Bagget June 5th, 2008 The Conflict Tradition McDonaldization of Culture George Ritzer presents in “The Weberian Theory of Rationalization and the McDonaldization of Contemporary Society” this grim view of today’s world, as seen through the eyes of Max Weber’s theory: “we seem closer to the iron cage of rationalization today than was the case in Weber’s day” (Ritzer 1998: 59). Nowadays, this iron cage has taken the form of The McDonaldization of Society, “the ultimate irrationality of formal rationality” (42). His basic premise is that Weber’s diagnosis and predictions of the effects that bureaucracy, as an extreme expression of rationality, would have on society have actually been taken one step further in our times through the fast-food mentality. He suggests that the rational principles employed by the kind of restaurants of which McDonald’s is the best-known chain have extended into areas of our culture as diverse as racehorses, medicine and child-care. It is my intention to describe his theory and share my view of McDonaldization as a fascinating, yet weakly supported perspective. To illustrate his point, Ritzer analyses each of Weber’s five dimensions of rationalization, providing examples to serve as proof of today’s formal rationality. Thus, he finds the extreme of efficiency in the tendency of turning the customer into an unpaid laborer: spending a few minutes everyday as sandwich-makers, salad chefs, soda jerks, gas station attendants, and bank tellers, all of these without receiving any pay (45). Similarly, calculability is to be found in the obsession with quantity above quality (whoppers, Big Macs, number of credentials, weight loss, 1 number of publications, etc); predictability can be seen in the comfort that we take from movie sequels, microwavable dishes, the shopping mall and even the daily newspaper. Increased control and replacement of human by nonhuman technology are analyzed together in the examples of home cooking, optical scanners in supermarkets and telemarketing. Finally, the author explores the irrational rationality of today’s iron cage, opposing the benefits of a McDonaldized world to the damages it might be doing to our society. He presents what I believe to be a fair assessment of some advantages of this pursuit for efficiency, even contrasting them to the situation in a country such as Cuba. However, he is quick to point out that those positive effects might be overwhelmed by the negative ones, and even suggests that while we might think we want these efficient solutions, “many people, however, persist in the belief, fueled by endless propaganda” (56). What I find to be especially fascinating is the idea that this seeming freedom (choosing your own salad, getting your money whenever you want, having so many choices at the shopping mall) could in fact be a disguise that keeps us content in our modern iron cage. In that sense, I believe that Ritzer’s theory is well constructed and even results in excellent material for proper understanding of Weber’s ideas on rationality. Nonetheless, it would appear that the author is constantly drawing absolute conclusions out of very specific and even extraordinary cases. After one such instance, he confidently states: “dentistry, medicine, child care, the training of racehorses, newspapers, and television news have come to be modeled after food chains” (44). However, one McPaper and one McDentist do not make up the whole world of journalism or healthcare. Specifically in the case of the former I find fault with his argument; I do wholeheartedly agree with the suggestion that newsgathering organizations are giving more into the tendency to deliver news at a fast, hard pace (47), causing great loss in quality and contributing to political and social deterioration in some cases. Yet, I 2 hardly see this propensity in journalism as arising from the fast-food system or even from the quest for efficiency. For this area, as for others that he exemplifies, I believe the situation to be more complicated: a faster-moving way of life, in which formal rationality is one of the central elements but not the only, and perhaps not even the most important one. Taking the above into account, I do believe that this theory deserves to be explored further and considered in other areas. One of them could be the internet, and they way it is changing many aspects, from small to fundamental, in our everyday lives. With its virtual stores, virtual chats, emphasis on speed, and huge reach, the World Wide Web is an ideal place in which to find modern examples of predictability, calculability, efficiency, increased control and replacement of human by nonhuman technology. Therefore to me, the most value to be taken away from Ritzer’s McDonaldization is the incentive to question the very idea of efficiency; to have in mind this other perspective to be contrasted to common discourses of the blessings of modernity, and specially when trying to understand the implications of new technological developments. Throughout the reading of Ritzer’s argument I found myself wondering, what else that we think to be the most efficient alternative is actually irrationally inefficient? Without surrendering to the author’s dramatic conclusions, one can still sharpen an awareness of the direction that our culture is taking in many different spheres. 3