Syntax Help

advertisement

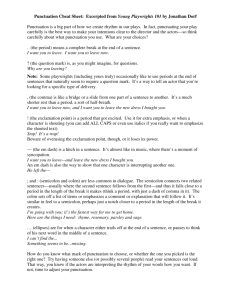

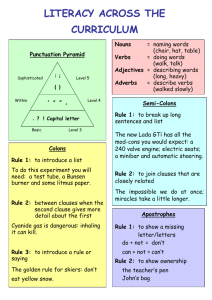

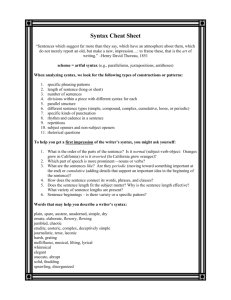

Syntax Help introduction Syntax- the way words are arranged into sentences; sentence structure and punctuation Includes: Sentence parts, word order, sentence length and punctuation Just like film directors play with the way that scenes come together, expert writers experiment with the way we express ideas. You don’t need to know what the subjunctive mood is, to study syntax, but you do need a basic sentence vocabulary: subject, verb, clause, phrase, and fragment. You need to understand how writers use these sentence parts to get the effects they want. You also need to have a strong understanding of punctuation, especially, the semicolon, the colon, the dash, and italics. Sentence PArts Subject- the topic of the sentence Verb- expresses action or connects the subject with the other words of the sentence Clause- a group of related words that has a subject and a verb Phrase- a group of related words that has NO subject or verb For example: The lion ran into the wilderness The first part is a clause because it has S +V and the words are all related. The second piece is a phrase because the words are related but it lacks S and V All complete sentences are one or more clauses put together. That’s all you need to know. Sentence Fragments Sentence fragment- a group of words that looks like a sentence and is punctuated like one, but does not meet all of the criteria for being a sentence. Most often it lacks a subject or a verb but it also may not express a complete thought. While in formal essays, fragments aren’t used, expert writers know how to use sentence fragments and often do. Word Order The normal order in English is subject first, then the verb and other details. Changing word order, can significantly change the meaning in the sentences below. Jim said that he drives only a truck. (He drives nothing else.) Jim said that only he drives a truck. (No one else drives a truck.) Jim only said that he drives a truck. (The speaker thinks he probably doesn’t really drive a truck.) Only Jim said that he drives a truck. (No one else said it.) We learn early that in English subjects come first, then verbs, then details. We also figure out that description words come before the words they describe. While word order in English is pretty inflexible, there is room to change things around. Expert writers sometimes do this for special effect or for emphasis. For example: Am I ever happy about my report card! Pizza I want- not soup. The first sentence reverses the order of the subject and the verb, am before I. The second sentence puts the detail of pizza in front of the subject and verb. Putting the words of these sentences in an unusual order catches the reader’s attention and emphasizes ideas. Punctuation A word about punctuation. (Did you notice that was a sentence fragment?) Students often think punctuation is a bunch of overly complicated rules used to torture them. Punctuation, however, can really be power in writing- it controls the way readers read your work. When speaking, pauses, vocal inflections and facial expressions help people understand us. Remember that only 7% of the message is from the words themselves. Writing has to depend on punctuation to do all that work and helps find-tune what we really want to say. The punctuation marks that expert writers use most to craft voice are: semicolon, colon, dash, and italics. The semicolon joins two or more clauses when there is no connecting word (and, but, or, for, nor). When a semicolon is used, all clauses are equally important and the reader should pay equal attention to them all. Example: He is my best friend; I have known him most of my life. The colon tells readers something important will follow. It’s very important not to confuse the colon and the semicolon. A semicolon functions like = , but the colon works like >. Example: He is my best friend: he helps me through hard times and celebrates good times with me. The dash marks a sudden change in thought or sets off a summary. Parentheses can do this, too, but the dash is more informal and conversational. Because parentheses are bigger and come in pairs, they’re more jarring to read; it’s like a stage whisper. They can only be used a time or two in a piece before they get a bit annoying. Example: John- my best friend- lives right down the street. Italics are used to talk about a word as a word, to show that a word comes from another language, and for emphasis. They should be used sparingly. When handwriting, underlining is used instead. Example: Of all the people I’ve ever known, John is my best friend. Sentence length Sentence Length is another important part of syntax. Sentences come in all shapes and sizes from one word (Help!) to very long and complicated sentences. You probably have developed a habit of sentence writing that you use with most of the sentences you write. Expert writers deliberately vary sentence length to keep their readers interested and to control what their readers pay attention to. Modern writers put the main ideas in short sentences and use longer sentences to expand and develop their main ideas. The goal is, always, for you to become more aware of the writing tools you have at hand and how to use them better. Conclusion The best way to master syntax is to read, read, read. Reading the works of expert writers helps imprint good syntax in your brain. Paying attention to the details of the way these writers use syntax to craft their message will help your own syntax improve. Experiment with different syntax in your own writing. It’s odd and you won’t always get it right, but it’s worth the effort: syntax is a powerful tool for expressing your voice. Sentence Structure – Analyze sentence structure by considering the following: A. Examine the sentence length. Are the sentences telegraphic (shorter than 5 words in length), medium (approximately eighteen words in length), or long and involved (thirty words or more in length)? Does the sentence length fit the subject matter, what variety of lengths is present? Why is the sentence length effective? B. Examine sentence patterns. Some elements to consider are listed below: 1. A declarative sentence (assertive) makes a statement, e.g., The king is sick. An imperative sentence gives a command, e.g., Stand up. An interrogative sentence asks a question, e.g., Is the king sick? An exclamatory sentence makes an exclamation, e.g., The king is dead! 2. A simple sentence contains one subject and one verb, e.g., The singer bowed to her adoring audience. A compound sentence contains two independent clauses joined by a coordinate conjunction (and, but, or) or by a semicolon, e.g., The singer bowed to the audience, but she sang no encores. A complex sentence contains an independent clause and one or more subordinate clauses, e.g., You said that you would tell the truth. A compound-complex sentence contains two or more principal clauses and one or more subordinate clause, e.g., The singer bowed while the audience applauded, but she sang no encores. 3. A loose sentence makes complete sense if brought to a close before the actual ending, e.g. We reached Edmonton that morning after a turbulent fight and some exciting experiences. A periodic sentence makes sense only when the end of the sentence is reached, e.g., That morning, after a turbulent flight and some exciting experiences, we reached Edmonton. 4. In a balanced sentence, the phrases or clauses balance each other by virtue of their likeness or structure, meaning, and/or length, e.g., He makes me to lie down in green pastures; he leadeth me beside the still waters. 5. Natural order of a sentence in English involves constructing sentences so the subject comes before the predicate, e.g., Oranges grow in California. Inverted order of a sentence (sentence inversion) involves constructing sentences so the predicate comes before the subject, e.g., In California grow oranges. This is a device in which normal sentence patterns are reversed to create an emphatic or rhythmic effect. Split order of sentences divides the predicate into two parts with the subject coming in the middle, e.g., In California oranges grow. 6. Juxtaposition is an artistic, poetic and rhetorical device in which normally unassociated ideas, words, or phrases are placed next to one another, creating an effect of surprise and wit, e.g., “The apparition of these faces in the crowd; Petals on a wet, black bough.” (from “In a Station of the Metro” by Ezra Pound). 7. Parallel structure (parallelism) refers to a grammatical or structural similarity between sentences or parts of sentence. It involves an arrangement of words, phrases, sentences, and paragraphs so that elements of equal importance are equally developed and similarly phrased, e.g., He was walking, running, and jumping for joy. 8. Repetition is a device in which words, sounds, and ides are used more than once for the purpose of enhancing rhythm and creating emphasis, e.g. “…government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” 9. A rhetorical question is a question which expects no answer. It is used to draw attention to a point and is generally stronger than a direct statement, e.g., If Mr. Ferhoff is always fair, as you have said, why did he refuse to listen to Mrs. Baldwin’s argument? C. Examine sentence beginnings. Is there good variety or does a pattern emerge? D. Examine the arrangement of ideas in a sentence. Are they set out in a special way for a purpose? E. Examine the arrangement of ideas in a paragraph. Is there evidence of patterns or a particular structure.