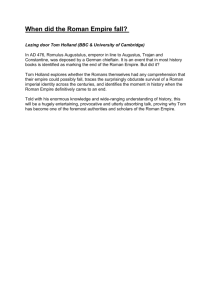

The Western Provinces

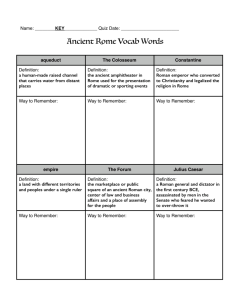

advertisement