Cemetery Demographics

advertisement

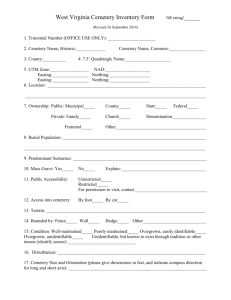

Cemetery Lab p. 1 CEMETERY DEMOGRAPHY (LICHENS) Written by Anne Pringle for Harvard’s Mycology Class (“Biology of the Fungi, OEB 54) Introduction: Births and deaths are the ecological currency of populations. If we ignore migration, the number of individuals living at a site at one time point (Nnow) is equal to the number previously there (Nthen), plus the number of births (B), and minus the number of deaths (D): Nnow = Nthen + B – D By understanding the numbers of births and deaths that happen over time we can learn a great deal about the biology of a population, for example, in populations with vast amounts of infant mortality only a few individuals become reproductive and so the genetic diversity of a single population experiences repeated bottlenecks. The diversity of different populations may diverge and become very different. In populations where every individual becomes reproductive genetic diversity may be more evenly distributed across the landscape. Data on births and deaths are usually part of a demography. One way to record data on births and deaths is to follow a population of individuals over time at one site. Obviously it would be impractical to collect this kind of information in an afternoon. A second way to take data is to record a stationary demography. In this kind of demography the ages of every individual of a population are recorded at one time point, and processes of births and deaths are inferred. Either kind of demography is exceedingly difficult to do with fungi, as most individuals are underground and cannot be seen. However (as you know!), lichens grow aboveground and are visible. We will attempt to collect a stationary demography of a population of lichens in this laboratory. It would be useful for you to work as pairs or in groups of three, and it would be interesting if different groups chose different species. Instructions: 1. Identify a morphological species. Look at the lichens around you and note color, whether there are sexual reproductive structures (usually these will be apothecia), if there are asexual propagules (isidia or soredia), and if there are any other obvious morphologies. Choose one ‘species’ to work with and write a short description of that species here: Cemetery Lab p. 2 2. Choose a gravestone with an abundance of that species. Record any information about that gravestone here, e.g. names and dates of the persons buried underneath (we may or may not use this information): 3. Compile a table in which you give a unique label to each individual (it is sometimes useful to use masking tape to GENTLY mark those individuals on which you’ve already collected data), and record its diameter using a plastic ruler. Record populations of the morphospecies on at least two gravestones. Lichen No. (Individual Label, e.g. 1, 2, 3, etc.) Diameter at Widest Point (use the metric system!) Notes (including, IF THERE ARE SEXUAL STRUCTURES, how many apothecia are found) Cemetery Lab p. 3 Cemetery Lab p. 4 Cemetery Lab p. 5 4. Move to different gravestones until you have collected data for at least 100 individuals of the same morphospecies. If you’ve started a gravestone and need to record more than 100 individuals to finish it, please do so. 5. Assume that size is roughly equivalent to age. Use your raw data for diameters to answer the following questions, but understand that we are using an assumption. 6. Count the number of individuals in each age group. Cemetery Lab p. 6 7. Make a GRAPH of your data with age (=diameter!) on the x-axis and no. of individuals per age group on the y-axis. Send a copy of this graph to Anne, Don, and Ben! We will post the data on our class website so that you can compare across morphospecies. Homework: Please use your data, and the data of others, to answer the following questions: A. Are most individuals of the morphospecies you identified young, or old, or are individuals evenly distributed across ages? What does this tell you about birth rates and mortality (are there odd bumps in your graph, indicating a large number of births at some time X number of years ago, or are the greatest number of individuals very young, suggesting infant mortality? How old is the oldest individual? What patterns explain your data?)? Are the same things true for other morphospecies? B. If you used two or more gravestones, compare the population structure across gravestones, is it similar? Speculate on why, or why not. C. If your species is sexually active, when? Do even very young lichens possess apothecia? What about other morphospecies?