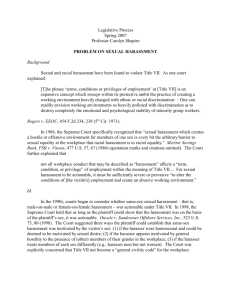

Week Three Materials (Complete)

advertisement