Global Exposure:

The Development of Engineering Study Abroad Programs at

Brigham Young University

A Personal Geography

Alan Parkinson

Ira A. Fulton College of Engineering and Technology

Introduction

This paper is a narrative account of the development of technical study abroad programs

in the Ira Fulton College of Engineering and Technology at Brigham Young University

(BYU). The narrative begins by establishing some context: both personal (the context and

background of the author) and general (the context and background of the students and

university). The narrative then proceeds to a discussion of the development of a college

strategy which incorporates global awareness as one of five strategic outcomes. Our

efforts of the past two years, which have involved sending students to China, Europe,

Mexico, Peru, Tonga, and Romania, are then presented. The narrative concludes with

observations about what we have learned, and what we yet hope to do and accomplish.

About Me

I feel it would be appropriate to start with an introduction of myself. I have taught at

BYU now for 26 years. I arrived in 1982 as a newly minted Ph.D. in Mechanical

Engineering from the University of Illinois. My research interests have included

optimization methods and engineering design. After going through the normal academic

advancement, I was appointed chair of Mechanical Engineering (ME) in 1995. I later

served as an associate dean from 2003 to 2005, and now as dean of the college.

Since my experiences as chair have directly influenced how I see the world now, I will

briefly describe that period in my career. The time was one of both professional

satisfaction and disappointment. On the plus side, we were able as a department to define

a strong overall vision. We saw an increase in all areas of resources: budgets, space and

faculty. This was also during the time frame of ABET 2000, which acted as a strong

driver for change in engineering education. I was very much in favor of both expanding

the set of desired attributes for engineers and moving from a prescriptive accreditation

approach to an outcomes-based approach. However, the path to achieving ABET 2000

objectives was not very clear, and we spent a fair amount of energy figuring out how to

proceed. And, as is still the case, some faculty members were skeptical that the changes

were worth the cost or would lead to lasting improvement. To complicate things during

our deliberations, we were asked to absorb another department which was being

disbanded. Those faculty wanted to continue their program as a separate program within

ME; this was resisted by many ME faculty. As might be guessed, this led to a lot of

discord. Also, because research funding for the department lagged behind those of our

sister departments, we came under a fair amount of pressure to improve. Eventually we

put our ABET 2000 efforts on hold and turned our entire focus to improving scholarship

and research funding. I came to understand that it is very important to pay attention to the

1

agenda of those over you. And I felt the sting of criticism of faculty who felt things

should be done differently.

I often pondered during this time how to best effect change in an organization as

seemingly complex as a department, where change must occur through consensus

building and group effort. I came to several conclusions, which are still being evaluated

in the even more complex environment of a college with 11 programs. First, I came to

feel that it was better to focus on a few key areas and make measurable progress in those

areas than to try to move ahead on a very broad front. Second, there comes a point where

it is better to make a decision and move ahead than to continue to discuss and debate a

course of action. If the process which has been followed is sound, then it is better to

move forward, albeit imperfectly, than to continue in indecision. Third, in the context of a

organization which still has teaching and research to attend to, change is accommodated

better if done at a slow and sustained pace, rather than through a huge, one-time effort.

My interest in organizations led to a somewhat unusual diversion in 2001. Having

finished my term as chair, I decided to enroll in the executive MBA program at BYU. I

had often wanted to learn what they teach at the business school, and I figured it couldn’t

be more convenient, since I work at the university. Still, however, it was a little strange to

go back to school and take tests and write papers and receive grades, sometimes from

colleagues I worked with on university level committees. So for two years I went to

school at night and during the summer to complete my MBA degree. This deepened my

interest in and appreciation for areas such as strategy, organizational change, supply

chain management, and product marketing and development.

In 2005 the term of the current dean came to an end. At this point I had served as

associate dean for two years. I was asked to apply. It was with some hesitancy that I did

so. I did feel, as I did when chair, that the college should move ahead more aggressively

in defining a strategy to address the challenges confronting engineering and technology.

At one point as associate dean I presented to the faculty the idea that the rise of skilled,

inexpensive engineering workforces in China and India could act as “disruptive

innovation”1 relative to engineering in the United States. U.S. engineers therefore needed

to add additional value, beyond technical skills, to remain competitive in the worldwide

marketplace. Somewhat to my surprise, I was appointed dean in 2005.

About BYU

Now, a little bit about BYU. Brigham Young University is one of the largest private

universities in the United States, with approximately 31,000 students. Students come

from all 50 states and more than 50 countries. It is a religious institution, supported

entirely by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter referred to the LDS

Church). It has a relatively unique student body. The freshman class of 2008 has an

average ACT score of 28, which corresponds to the 92nd percentile. By the time they are

juniors or seniors, most of the men and about half the women have served as missionaries

for the LDS Church. This service often involves learning a second language and living in

Clayton Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma, When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail,

Harvard Business School Press, 1997

1

2

another country for 18 months to two years; even if the missionary service is in the

United States it is common to learn another language and be exposed to a new culture. As

an example, I served a mission in Japan 35 years ago; my daughter served in Russia. My

associate deans served in Spain and Mexico.

In addition to academic qualifications and relatively unique cultural experiences, another

attribute of the student body is leadership potential. For example, in the freshman class,

28% of the students were high school student body officers or team captains. As part of a

mission, a seasoned missionary (meaning they are 20-21 years old instead of 19) might

be responsible to direct the efforts of a district (8-10 missionaries) or a zone (20-50

missionaries). LDS youth also have numerous leadership opportunities and mentoring

while growing up. Groups of young men and women take turns serving in leadership

roles among their peers in age groups 12-14, 14-16 and 16-18.

Reflective of another dimension of the student body, students at BYU commit to live an

honor code which stresses honesty and integrity. The honor code is typically not

something which exists external to the students’ values, but is rooted in deeply held

religious beliefs. I do not wish to imply that BYU students are unusual or unique in

aspiring to these character traits, but this overt pledge does form a strong foundation upon

which to build a commitment to professional ethics.

The College Strategic Plan

Within this context of strengths of the student body, I wish to discuss how and why the

college leadership evolved to particular strategic plan. With a change in college

leadership three years ago, it was a natural time to contemplate strategic directions for the

college. BYU represents an enormous investment by the LDS Church, which covers

about 70% of the operating expenses—an investment of hundreds of millions of dollars

per year. In consideration of this investment, and in consideration of the significant

potential of the student body, we felt to ask ourselves questions such as, “How do we

become better than we are now?” “Can we be a leader among engineering colleges, and,

if so, how?” “How do we prepare our students to succeed in an increasingly global,

competitive engineering environment?”

Certainly many engineering colleges have asked similar questions. It appears that many

have decided that a path to excellence lies in increasing their research activities and

reputation and growing their graduate programs. There is no question that numerous

benefits and prestige accrue with increasing levels of research.

For BYU, however, the path must be different. The Board of Trustees for the university

has determined that BYU should remain primarily an undergraduate institution. Currently

the graduate program is about 10% of the size of the undergraduate program. Although

this might grow some, it will not grow a lot. The path to excellence for BYU will not be

to become a major research university. It must focus primarily on being an excellent

undergraduate institution.

3

If that is the case, how might this path be defined? Concurrent with our deliberations of a

college strategy, the National Academy of Engineering released the document, “The

Engineer of 20202,” which discusses the forces acting on engineering in the United States

and what preparation engineers will need to be competitive in the global economy. This

report has been accompanied by a number of other publications which support its

conclusions. The report indicates that the skill set for engineers needs to expand beyond

analysis and technical ability to include communication skills, leadership skills,

creativity, adaptability, ethical responsibility and a commitment to lifelong learning.

This set of desirable skills overlaps well with the strengths of BYU students. Given the

particular skill set and experiences which BYU students bring to the table, the strategy

which we have developed is to play to our strengths by developing students with the

characteristics of technical excellence, leadership, global awareness, character (i.e. a

strong sense of professional ethics) and innovation. We have arranged these five

attributes into an acronym called “LIGHT,” as given in Fig. 1 below. We wish to

leverage off of the life experiences and preparation our students have to develop a strong

combination of attributes in these areas. By so doing we desire to position our students to

succeed, to provide what the workforce wants, and to be an influence for good. The goal

is for the college to be a leader, and to be excellent, in part, by the type of graduates we

produce. By following this strategy we hope to achieve several objectives at once, which

we refer to as “hitting the target,” as illustrated in the Figure 2 below.

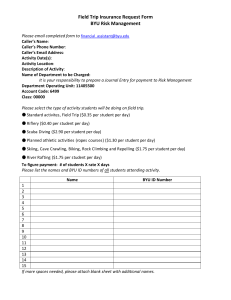

Fig.1. The five areas of focus for the college.

2

National Academy of Engineering Committee on the Engineer of 2020, G. Wayne Clough (Chair), The

Engineer of 2020, National Academy of Engineering Press, 2004.

4

Fig. 2. The converging of several objectives through the college strategy

Global awareness forms an important element of this strategy. One means of developing

global awareness is through technical study abroad programs. Our efforts here began in

earnest two years ago. Because a number of engineering colleges were already active in

this area, it made sense to study what other universities were doing. As part of my own

scholarship, I decided to study and then write a paper on engineering study abroad

programs. I reviewed about 25 programs, identified nine different formats, and tried to

infer both challenges and strengths of the various formats as well as best practices.3

With study abroad, there is really no substitute for experience. So in 2007 we decided to

get our feet wet and learn by doing. We ran several different kinds of programs in five

countries: China, France, Mexico, Tonga and Romania. These will be described next.

BYU Programs in 2007

In 2007, about 85 students participated in seven different study abroad programs. These

programs included a mentored travel program (China), an extension program (France), an

extended field trip program (Romania), two service learning programs (Mexico and

Tonga), an international design project called PACE (ten countries), as well as a half

dozen internships (Asia). Each of these programs has its own set of learning outcomes,

although many outcomes are shared. The following discussion closely follows that given

in a previous paper.4

A Parkinson, “Engineering Study Abroad Programs: Formats, Challenges, Best Practices,” Online

Journal for Global Engineering Education, 2.2, 2007. See http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/ojgee

4

A. Parkinson, J. Harb, S. Magleby, C. Pate, “Extending Our Reach: What We Have Learned in Two

Years of Engineering Study Abroad Programs,” Proceedings ASEE Annual Conference, Paper AC 20008862, 2008.

3

5

China

The mentored travel program in China took place over six weeks. Based on preliminary

work by two faculty members who visited a number of Chinese universities to better

understand options, we decided to partner with Nanjing University. Nanjing, with whom

BYU already had a relationship, was willing and able to provide lodging, classrooms and

instructors for visiting students. Students participating in the program took one of two

classes taught by Nanjing faculty, Business Chinese (for those students who already had

some Mandarin proficiency) or Beginning Chinese. In addition, all students took a course

entitled “Globalization, Engineering and Technology” taught by the BYU professor who

directed the program. As part of this course, students completed projects on some

element of globalization that interested them. Courses were augmented with visits to

engineering companies and cultural sites in Shanghai, Beijing, Nanjing and Xi’an.

Photographs of this group are shown in Figs 3 and 4.

Fig. 3. Students at Nanjing University in

China taking classes

Fig. 4. Students on a cultural visit.

This was a strong program for several reasons. First, students had a structured,

challenging classroom experience. This classroom experience was then augmented with

out-of-classroom visits to see cultural and industrial sites. Perhaps the greatest strength of

the program was that it was designed around global issues critical to engineering and

technology. The students were able to learn about these issues and experience them first

hand. The mentored travel paradigm scales relatively well—we were able to provide this

experience for 17 students and could accommodate about 25 at a time in the future.

France

The France program was an extension program done in partnership with Georgia Institute

of Technology, which operates a permanent facility in Lorraine, France. During the

summer program, GT-France offers about 25 courses, including a variety of sophomore

and junior level engineering courses as well as courses in the French language. Most

courses are taught by GT faculty in English. Seven BYU students participated in the

summer program. Fridays and weekends were left free; students were encouraged to

travel during this time. In addition, BYU arranged for several company visits, including

an outstanding visit to Airbus. Fig. 5 shows the students in this program.

6

Fig. 5. Students at GT-France.

Although students had an enriching experience touring Europe (while taking required

engineering courses), their exposure to and understanding of globalization issues, one of

our main objectives for this type of study abroad program, were weak. We decided in

2008 to augment this program with a program of our own in Europe. This new program is

being patterned after the successful China program. We think a more structured program

will result in better achievement of objectives.

Romania

The program in Romania was an extended field trip format. Students were invited to

Romania to make presentations to Romanian engineering students on engineering ethics.

While there, they also toured major construction sites. Seven students participated. We

are unsure of the long term outlook for this program. Figs. 6 and 7 show students in this

program.

Fig. 6. Students making a presentation to

colleagues in Romania on engineering

ethics

Fig. 7. Touring a construction site in Europe.

Mexico

This program is a service learning program tightly coupled to a Civil Engineering course

on hydrologic modeling. At the beginning of the semester professors at BYU and partner

7

universities in Mexico met to select a number of real water projects of interest that could

be modeled using software developed at BYU. Possible projects involved analyzing and

making recommendations regarding water runoff, ground infiltration, flood control,

reservoir management and mitigation of adverse effects on water quality. Student teams

were formed for each project at both places and these teams worked together via email

and the Internet. Before traveling, the teams defined the problem, determined objectives,

developed and completed tasks and performed preliminary modeling. Most of the

communication was conducted in Spanish. Towards the end of the semester, BYU

students traveled to Mexico for two weeks and met with their Mexican counterparts.

They visited the actual sites, met with stakeholders, refined their models and made final

recommendations. Project presentations were given in Spanish. Last year 17 students

participated. Pictures of this program are given in Figs. 8 and 9.

This program has existed for several years. Previously the professor directing the

program was inclined to discontinue it because, frankly, he wasn’t sure it was valued.

The emphasis of the college in support of these programs has reinvigorated the faculty

director. We also have provided financial support for the past two years to help with the

logistics.

This has been a strong program. Students not only gain cultural sensitivity, they learn

about working in multi-national teams, gain problem solving skills (working on real

projects) and learn sophisticated software well enough to help teach it to others. Students

are exposed to the vocabulary of professional Spanish. Several students have considered

this to be the most significant learning experience they have had at the university.

Fig. 8. BYU and Mexican student groups.

Fig. 9. A BYU and Mexican student

team work together.

Tonga

This program was a service learning project associated with Engineers Without Borders,5

a chapter of which was started at BYU in 2006. For the inaugural project, students

developed and implemented a small scale facility for the conversion of coconut oil to biodiesel fuel on the Pacific island of Tonga.

5

http://www.ewb-usa.org/

8

To prepare for this project, students enrolled in a new course titled, “Global Projects in

Engineering and Technology.” The course was open to all disciplines and counted as a

technical elective. As part of the course, students worked in multi-disciplinary teams on

one of six elements of the project. Students focused on developing appropriate,

sustainable technology. They built, tested, and refined the hardware for the project. 6

At the end of the semester, twenty four students traveled to Tonga to set up a pilot biodiesel facility. The trip was ultimately successful; however, the group did experience a

number of difficulties. The main problem was that much of the supplies and hardware

they had pre-shipped to the island had not arrived when they got there. Getting the

supplies the last leg to Tonga in time for them to be used was itself a lesson in cultural

differences. In the end students were able to demonstrate the bio-diesel process to local

farmers as well as to government officials, and the trip was judged a success. Figs 10 and

11 show the students in Tonga.

The strengths of this program were similar to the Mexico program. Students enjoyed

using their engineering skills to help others. They learned about problem solving and

gained leadership and team experience. Students also learned from the difficulties—they

learned that sometimes the biggest obstacles to success are not technical in nature. For

2008 the project is in Peru.

Fig. 10. Students in Tonga for Engineers

Without Borders project.

Fig. 11. Students demonstrating bio-diesel

process to selected government officials.

PACE

The last program discussed here is not a study abroad program, but it very much fits as

part of global engineering. It is known as “PACE,” which stands for Partners for

Advancement of Collaborative Education, a consortium of companies (led by General

Motors) and universities, which agree to work together to provide students with

international collaborative CAD/CAM experiences. Acting as the lead university, BYU

students coordinated the efforts of 20 student teams across the globe, including teams in

China, India, Korea, Sweden, Germany, Brazil, Mexico and Australia, in designing and

A. Frankman, J. Jones, W. Vincent Wilding, R. Lewis, “Training Internationally Responsible Engineers,”

Proceedings ASEE Annual Conference, Paper AC 2007-301, Honolulu, HI 2007

6

9

building a Formula 1 style racecar.7 Subsystems were designed and built by student teams

at their own universities; these systems were assembled at BYU into a working vehicle.

In some instances BYU students traveled to other universities and trained students there

in the use of software tools.

The project obviously had a very heavy design flavor to it. Students gained experience in

design, teamwork, project management and leadership. Students learned how to

communicate with other teams around the world using software tools as the lingua franca.

They also learned of some of the challenges associated with building hardware in

multiple locations and in working across multiple time zones.

Fig. 12. BYU PACE members pose in front of the vehicle built as part of the PACE

project.

BYU Programs in 2008

In Spring of 2008, we ran our second set of programs. Students are all over the world as I

write this paper. We are implementing a repeat of our China program at Nanjing

University, a new program in China with a focus on “mega-structures” (large dams,

bridges and buildings), a second project for Engineers Without Borders, which is in Peru;

a repeat of the Mexico program, a new program in Europe (21 companies, four

universities and eight countries in four weeks), a new PACE project, and several

international capstone projects, including projects in Ghana and Tanzania. These

programs involve approximately 125 students.

Reflection

As we now enter our second year, I feel a need to enter a time of reflection. Here are

some of the questions and observations about our experiences so far.

1. First, and perhaps most important, are these programs worth the cost? Are

students learning what they need to learn and should learn through these

programs? It is the case that these programs are expensive both in terms of cost

faculty time. I have to say that the initial results look promising but are yet

unknown. Some faculty expect students to have “transformative” experiences as a

M. Webster, D. Korth, O. Carlson, C. G. Jensen, ‘PACE Global Vehicle Collaboration,” Proceedings

ASEE Annual Conference, Paper AC 2007-1817, Honolulu, HI 2007

7

10

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

result of these trips. That is a pretty high standard to meet and not one we apply to

anything else in the undergraduate program. Nevertheless, from visiting with

faculty directors and from accompanying students on these trips, I believe that

many students do have life changing experiences. These experiences can be the

result of gaining a perspective on themselves as members of a global community,

or arise from a new view of their possible career paths as professionals working in

a global setting. In this regard, students are sometimes anxious about working

outside the U.S. A study abroad experience can quiet fears and help them see this

is an opportunity they should consider.

Assessment of these programs continues to be a challenge. Although we have a

set of general outcomes for each type of format, we ask each director to identify a

set of learning outcomes specific to the particular program (Tonga, Europe, etc.),

share these with the students beforehand, use them to drive discussion and

learning, and have the students self-assess if these have been reached. This kind

of indirect assessment is not as meaningful as more direct measures. We have

investigated the Intercultural Development Inventory8 as one possibility here, but

we are still considering whether this is a good instrument for us.

We have focused on several specific study abroad formats: mentored travel,

extended field trip, service learning and international design, partly because these

programs scale relatively well. This has allowed us to ramp up relatively quickly.

Nevertheless, each these formats are limited to about a maximum of 20 students

per program.

The most important key to success is developing a cadre of faculty directors.

Anyone who has been a director of one of these programs knows it is a lot of

work, both in terms of the effort required before leaving and in terms of the hours

involved while abroad. One of our greatest concerns is providing rewards and

support for faculty so they continue to want to do this. In the future we may be

constrained in our ability to expand study abroad opportunities by the number of

faculty willing to be program directors. We have provided faculty who have

started new programs with fellowships and other support. For longer programs,

we encourage faculty to take spouse and family, if they desire. In the end, faculty

members are driven by the reward system. Although directing a study abroad

program cannot compensate for a fatal weakness in some other area of

performance, it is viewed very positively in the college and has been a positive

factor in rank advancements.

The programs would not have happened without the support of the college

leadership. College support has communicated to the faculty that we value these

activities. We are in a position to direct resources to these activities and put “our

money where our mouth is.”

We have learned the importance of good student preparation before study abroad

begins. Based on our 2007 experience, we are moving to having a common

preparation seminar for all programs (with some breakout sections focused on

8

The Intercultural Development Inventory is a 50 item, paper and pencil instrument that empirically

measures five orientations toward cultural difference based on the Developmental Model of Intercultural

Sensitivity. Contact the Intercultural Communication Institute, Portland, Oregon. Email:

idi@interncultural.org or http://www.intercultural.org

11

particular areas or countries of the world). Ideally students should receive some

exposure to four areas: 1) cultural issues, such as cultural diversity,

ethnocentrism, communication across cultures, 2) country issues, such as a brief

introduction to a country or region’s history, economy and politics, 3) study

abroad issues, such as handling money, safety and health, and 4) globalization

issues, such as trade policy, outsourcing, intellectual property and technology.

Two of the preparatory reading resources used at BYU have included,

Globalization, A Very Short Introduction,9 and The Cultural Dimension of

International Business.10

7. These programs are synergistic with another college goal of increasing women

enrolled in engineering and technology. About 25% of the participants have been

women (which is, sad to say, double the percentage of women in the college).

Surprises

I have been a little bit surprised regarding how I have come to feel about humanitarian

projects. Previously I viewed study abroad as a way to learn what developed countries

were doing and how to prepare our students to remain competitive in the global

marketplace. However, I have come to understand that another motivation for promoting

international technical experience relates to the range and scale of technological needs of

humankind in the 21st century. Some of the most challenging technical problems facing

the world include providing for clean water, sanitation, infrastructure, energy, health care

and transportation to the majority of the world’s population which lives in developing

countries on meager resources. In Fig. 13 below I show one of these projects: a hand

operated coconut press for women in Tanzania. This was an excellent learning experience

for students to both gain skills in design and to learn intercultural sensitivity, and it has

the potential to lead to a better life for the families of the village.

Fig. 13. Students in Tanzania demonstrate the operation of a coconut press.

9

M. B. Steger, Globalization, A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2003

G. P. Ferraro, The Cultural Dimension of International Business, Fifth Edition, Pearson, Prentice Hall,

2006.

10

12

I have also been surprised at how receptive donors are to humanitarian study abroad

programs. In general, donors are very supportive of study abroad programs. They see this

as an area where they can make a difference. Since many of them come from industry, I

think they value the importance of this type of experience. Donors especially like having

their gifts do double duty: helping students learn and helping people have a better life. As

dean I have become very active in fund raising, and I had not anticipated how responsive

donors would be to our venture into service learning. I am convinced that if handled

properly, humanitarian projects can be excellent learning experiences for students. There

is often synergy with other learning outcomes such as multi-disciplinary design under a

set of unusual constraints (i.e. third world constraints), teamwork, and open-ended

problem solving. Students also develop an understanding of themselves as member of the

world community and are often humbled by what they enjoy as citizens of the United

States.

I have been pleased that the load of running study abroad programs has been pretty

evenly split among departments. Our Engineers Without Borders directors come out of

the Chemical Engineering Department; China comes from Electrical Engineering;

Mexico and China Mega-structures are from Civil Engineering, and Europe is from

Mechanical Engineering. This dispersion of directors has allowed for load sharing across

the college and provided for a leavening influence as these directors are able to share

their experiences with their own departments.

Thoughts About Hitting the Target

Earlier in the paper I discussed the development of a college strategy which involved

“hitting the target.” After three years as dean, it is perhaps a good time to assess where

we are. Are we getting closer to hitting the target?

Before answering that question I would like to relate a recent experience which occurred

at the annual ASEE Engineering Deans Institute. The occasion was a session that

involved an industry panel with representatives from well known high tech companies.

These people were discussing what skill set they wanted in their new hires. They wanted

pretty much what a number of studies have proposed: not only a strong technical

understanding, but also leadership skills, communication skills, high standards of ethics,

etc. During the question and answer session, one dean asked the question, “Since you are

asking for students to learn more, and the curriculum is already very full, what do you

propose we leave out? The assumption was that we could not add in more stuff without

pushing something else out. The reply of the panelist was instructive: “Nothing.” He

wanted it all. Whereupon another dean suggested that perhaps we should look at the M.S.

as the entering professional degree. This would allow for more time to cover more

ground. The panelists thought this might be a possibility. I could not help but wonder

about a third possibility: is it possible to improve our “educational productivity?” Each

year, the industrial sector becomes more productive by 3-4% per year. This means it

produces 3-4% more per unit input of labor. Is there such a thing as educational

productivity? Can we produce more in four years than we have before because we are

working smarter and not just harder?

13

I would hope the answer to this question is “yes,” but I am not sure. Educators work with

a product that comes with its own will, motivation, preparation, etc. In general, at BYU

we are trying to hit the target through our five focus areas without giving up anything we

had before. It is a challenge. So far we have accomplished the following in the past 3

years:

In global awareness we now have about 125 students on some form of technical

study abroad.

In ethics and leadership we have a new course, approved for general education

credit (meaning the course counts towards graduation requirements), which

focuses on leadership and ethics in a global setting. About 150 students per year

are taking this course. We also held the first “Ethics Symposium” which involved

faculty and industry speakers. We have held numerous leadership seminars for

students. This fall we are introducing a leadership model to all faculty so they can

begin to integrate leadership activities into their courses. Leadership principles

can be learned, but leadership is developed through practice. We need to provide

for leadership practice as part of what we do.

In innovation we have started a one day “Innovation Boot Camp” patterned after a

short course offered at Stanford University. New prototyping labs have also been

developed. Admittedly we haven’t done much here—innovation is the focus of

college this coming year.

We aren’t where we wish to be, but I think we are making some progress. We still have a

long ways to go.

Intersections

As I understand it, a personal geography is not just about my own path, but includes the

path of others. I wish to acknowledge the help and support of my Associate Deans, John

Harb and Spencer Magleby. They have made a lot of this happen. I appreciate the

willingness of the faculty directors to try out this experiment of study abroad. We have

been fortunate that a few have had passion for doing this. I also acknowledge the faculty

in the entire college. Some are more enthusiastic than others, but most are supportive of

these directions. Many, I think, believe “we should either get on the train or we will get

run over.”

I don’t yet see how we might expand with programs which are significantly larger than

where we are right now. I feel we will figure this out better as we continue to gain

experience.

14