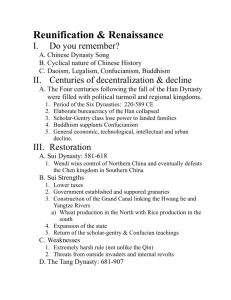

Buddhism in Tang Dynasty

advertisement

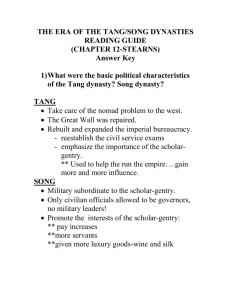

Buddhism in Tang Dynasty China Buddhism played a dominant role in Tang dynasty China, its influence evident in poetry and art of the period. Buddhism first entered China with traders following the Silk Roads and it began flourishing during the period of political disunity following the collapse of the Han Dynasty in 220 CE. Buddhist teachings spoke to the concern for salvation and release from suffering which is perhaps why it was so attractive to people living in that chaotic period. Various schools of Buddhism spread after the reunification of China under the Sui Dynasty in 589 CE and Buddhist influence reached its height during the three-hundred years of Tang rule (618-907 CE). Buddhism, religious Daoism, and Confucianism all coexisted as the "three teachings" under the Tang. However, some began to fear that traditional Confucian values about venerating ancestors and taking care of parents would fall by the wayside as men and women left home, joined monasteries, and became unmarried monks and nuns living far away from the graves of their ancestors. In addition, tax revenues and agricultural yields had also begun to fall off. These fears erupted in 845 CE. In that year, the Tang emperors moved to limit the wealth and economic power of landed Buddhist monasteries which did not have to pay taxes. The influence of Buddhism declined in China after the Tang and a new philosophy, called NeoConfucianism, emerged. NeoConfucian scholars disliked that Buddhism was “foreign,” and constantly spoke about how Buddhism undermined traditional Confucian values. Ironically, NeoConfucianism incorporated some elements of Daoism and Buddhism that were attractive to people, in a process of syncretism that satisfied more people within Chinese society. * Excerpted from: http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/ “Lives of the Nuns” Shi Baochang, writer of biographies of important Buddhist nuns, 516CE A young girl, An Lingshou, . . . delighted in the Buddhist teachings and did not wish for her parents to arrange her marriage. Her father said, “You ought to marry. How can you be so un-filial?” An Lingshou said, “My mind is concentrated on the work of religion. . . why must I submit three times, to father, husband, and son, before I am considered a woman of respectability?” Her father said, “You want to benefit only one person – yourself.” An Lingshou said, “I want to cultivate [Buddhism] because I want to free all living beings from suffering.” Linshou’s father then consulted a Buddhist magician who said that his daughter was a bodhisattva who, in her former life, “benefited all living beings.” The magician said, “If you consent to her plan, she indeed shall raise her family to glory and bring you blessings and honor.” Lingshou’s father returned home and permitted his daughter to become a nun . . . the nephew of the Emperor honored her and promoted her father to the official court position of undersecretary of the Yellow Gate . . . 1. What was the disagreement between An Lingshou and her father? 2. How was the disagreement finally resolved? In what way does Lingshou bring honor to her family…or not? 3. Why does the resolution of this story indicate that it could only have happened during the Tang Dynasty? “Memorial on the Bone of Buddha” Tang Confucian scholar Han Yu, 819 CE [Speaking to the Emperor] Your servant submits that Buddhism is but one of the practices of barbarians which has filtered into China since the later Han. In ancient times there was no such thing . . . In those times the empire was at peace, and the people, contented and happy . . . Now Buddha was a man of the barbarians who did not speak the language of China and wore clothes of a different fashion. His sayings did not concern the ways of our ancient kings…He understood neither the duties that bind ruler and subject nor the affections of father and son. If he were still alive today and came to our court by order of his ruler, Your Majesty might condescend to receive him, but . . . he would then be escorted to the borders of the state, dismissed, and not allowed to delude the people. How then, when he has long been dead, could his rotten bones, the foul and unlucky remains of his body, be rightly admitted to the palace? Confucius said, “Respect spiritual beings while keeping at a distance from them.” 1. What is the argument given by the Confucian scholar to the Emperor? 2. On what basis does the Confucian make his assertions? 3. In general, what does the Confucian scholar think about relics of the Buddha being admitted to the Emperor’s court? Tang Dynasty Prohibition of Buddhism Excerpt from edict issued by Emperor Tang Wuzong in the 8th month, 845 CE “We have heard that up through the Three Dynasties (Xia*, Shang, and Zhou circa 2000-221 BCE) the Buddha was never spoken of. It was only from the Han (202 BCE-220CE) on that the religion of idols gradually came to prominence. So, in this latter age, it has transmitted its strange ways, instilling its infection with every opportunity, spreading like a flourishing vine, until it has poisoned the customs of our nation; gradually, and before anyone was aware, it lured and confounded people’s minds so that the multitude have been increasingly led astray…It wears out the strength of the people with constructions…pilfers their wealth…causes men to abandon their lords and parents for the company of teachers, and severs man and wife with its monastic decrees. In destroying law and injuring humankind, indeed, nothing surpasses this source of age-old evil. To fulfill the laws and institutions of the ancient kings, to aid humankind and bring profit to the multitude, how could we fail to act? *The Xia Dynasy is a mythical dynasty in Chinese history, not fully confirmed by archaeology, but believed by some to have occurred before the Shang Dynasty of the Bronze Age 1. What metaphor does the emperor use to describe what, in his view, Buddhism is like? 2. On what SPECIFIC basis does the emperor make his decree to forbid Buddhist monasteries? You should note 3 or more. 3. What ulterior motive could the emperor have to limit monasteries? "On the River" by Du Fu, a neo-Confucian poet of the Tang Dynasty On the river, every day these heavy rains-bleak, bleak, autumn in Ching-ch'u High winds strip the leaves from the trees; through the long night I hug my fur robe. I recall my official record, keep looking in the mirror, recall my comings and goings, leaning alone in an upper room. In these perilous times I long to serve my sovereign-old and feeble as I am, I can't stop thinking of it 1. Why do you think Du Fu describes the river as existing at the end of a season? What could it be symbolizing? 2. What does Du Fu wish he could still do? In what capacity did most Chinese upper-class men do this? 3. How does Du Fu’s wish for his life reflect NeoConfucian values?