Language and Ethical Encounter: George Orwell on the Use

advertisement

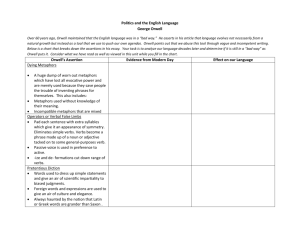

Language and Ethical Encounter: George Orwell on the Use and Misuse of Words Mark Sentesy For Jennifer Matthews Representations of the Intellectual 14 June, 2001 In 1946, George Orwell wrote an essay called Politics and the English Language, in which he discussed the misuse of English at the time. In it, he identifies several ways that writers write badly. As the essay progresses, he relates this misuse to politics. A political speaker will never say “I believe in killing off your opponents when you can get good results by doing so” (136).1 Instead, he will use a euphemistic, vague, and usually impersonal style to keep this meaning from the audience. This style of language is one way to misuse language, but is useful to a political speaker to disguise his meaning. For Orwell, the speaker’s dishonesty exemplifies the crisis of politics: he uses language to prevent the audience from seeing his meaning, and so from judging it ethically. The crisis of politics is an ethical crisis. But what is more disturbing, Orwell points out, is that probably the speaker does not see his meaning either. Thought affects language, and language affects thought. What is language, that it can hide my meaning from myself and from others, instead of revealing it? How can language affect my thought? The core of Orwell’s remedy to language is that a good writer encounters his thought in and through his writing. For him, the three ways to kill language and ethics are laziness, deception, and indifference. In examining these, we find an image of ethics as an encounter. There are three main voices with which we write: first, second, and third person. Only the second admits of an encounter that we could call ethical. In the second-person experience of the encounter we can find something of a ground for ethics. For Orwell, the experience of writing should be an ethical encounter. This is his remedy to politics. Language What is language for Orwell? Political and economic causes influence language (127). This implies that language is dynamic. Orwell does not elaborate on how economics affects language, but politics uses language for two purposes: evasion, and the prevention of thought. He discards the idea of imposing a “standard English” (138) because language is a tool that a writer should adapt to his meaning, and not the other way around (139). When language determines what a man intends to say, it may disguise or even distort his meaning. We learn to speak and write through imitation. Journalists, non-fiction and political writers, the likely targets of Orwell’s paper, imitate one another throughout their career. Like any writing, their writing has its fashion trends. This is how Orwell wants to clarify thought: by consciously changing the prevailing writing style (128, 137) by applying social pressure (140). “To think clearly is a necessary first step towards political regeneration” (128). Thought causes language, but language can shape thought (127-8). What is the relation between language and thought? Orwell is mainly concerned with writing, though his criticisms bear directly on speech as well. Writing is something with which one can work, as a potter works with clay. No matter how faint, the potter has some idea what he wants to create, for example, a tripod. Seeing the shape before him, he 1 All in-text references are to pages in George Orwell, Politics and the English Language in In Front of Your Nose 1945-1950. ed. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (London: Secker & Warburg). 1 then modifies and improves it. Since, for example certain shapes are unstable, the material restricts what he can imagine. At the same time, it provokes him to improvise a solution. In the process of working out his idea in the clay, the potter discovers and clarifies his idea. It is the same with writing: when I write, I learn what I think. If my language is clumsy or obtuse it may never reveal to me what I think. Losing One’s Meaning: The Misuse of Language According to Orwell, the misuse of language distorts and prevents thought, hiding it from the reader and writer (135). He discusses four common problems: dying metaphors, operators (verbal false limbs), pretentious diction, and meaningless words. He calls them swindles and perversions (133). All of them should be removed from one’s writing. Dying metaphors are those which are neither new enough to have an effect, nor old enough to have become an ordinary word (e.g. heart of stone). The purpose of a metaphor is to evoke a mental picture to clarify an idea (134). A dying metaphor has a meaning, but often both the writer and the reader are not aware of it, “for example toe the line, is sometimes written tow the line” (130). Orwell says that when a writer combines incompatible metaphors (e.g. “The Fascist octopus has sung its swan song”), he does not see the pictures that they evoke (134). This means he is indifferent to what he has to say (130), or worse, he is not thinking about it at all (134). The words in an image or metaphor point to objects of thought, e.g. an octopus (134). The writer as well as the reader should see, or encounter these objects, which is to grasp the meaning of the words. When a writer makes a phrase out of a simple verb, conjunction, or proposition, he has added a verbal false limb, says Orwell. Instead of break, or attack, he writes render inoperative, or militate against (130). Moreover, writers use the passive voice, and use noun constructions instead of gerunds (by examination of instead of by examining). The overall effect is that the reader and writer encounter a meaning, but are numbed by its swollen phrasing. A writer uses a pretentious style “to dress up simple statements and give an air of scientific impartiality” (131). An objective style covers up the voice of the author. In its examples, the style also reduces “a person” to “the individual.” One can never meet “the individual” because it is a universal, an “impersonal person.” Meaningless words are common in art and literary criticism, politics, and if I may say so, in religion and philosophy2 too. These words “not only do not point to any discoverable object, but are hardly even expected to do so by the reader” (132). Orwell gives the political examples of Fascism, which at best means undesireable, and democracy, which means desireable. Writers and readers can do this because each word has several meanings. The writer uses one meaning of democracy to 2 Though some would reply that this shows I am not clever enough to understand it, I think many words in, indeed the whole philosophy of Hegel aims at no discoverable object. He intends to think the concrete unity of subject and object. But where is this unity concrete, and for whom? 2 describe, say, the government of his country, and allows the reader to understand whatever meaning he likes. Thus, he uses the word dishonestly (133). Just as he disagrees with the idea of “Standard English,” Orwell does not say that we should flatten our words down to one meaning, for this would obstruct the usefulness and dynamism of language. The problem with dishonesty is not the words, but dishonesty. These four problems spring from one: to misuse language is to use it in a way that keeps the reader or writer from the meaning of the words. Orwell implies that this meaning is like an object that one sees, or meets, but perhaps a person’s encounter with the object is where it becomes meaningful, just as the pattern of tea leaves in a cup becomes meaningful only when it is interpreted by a soothsayer. Orwell does not address the feeling that something is meaningful before one knows its meaning. Watching two Italians yell at each other, I would think it is a serious fight, though I have no idea what they are saying. But as Orwell is probably aware, it is quite common that this feeling is misplaced: later one of the Italians would tell me that it was not really a fight. Orthodoxy, or How Not to Think It is clear that for Orwell the meaning of language is not in the language itself, but either in the object of thought one meets through the language, or in the meeting itself. Politics requires orthodoxy, and this requires a lifeless, imitative style of language. Orthodoxy creates dummies whose brains are not involved in speaking in the way that they should be (135-6). Why is it so lifeless? It must be stable, which means that people should follow, but not too well.3 Probably Orwell means that if a follower learned the details of the real situation that the orthodox position supposedly judges, he could easily disagree. Why is this? No orthodox opinion can account for the complexity of the real situation. Perhaps no opinion whatsoever can account for its complexity. For example, the conservative idea that people are on welfare because they are lazy is as false (and as correct) as an opposed position, that these people are only victims of their society. An orthodox statement rarely judges a real situation. Most of those who pronounce them have no contact with a concrete situation. Rather, the people who argue for them create a model of the problem from out of the statement, simply to apply it like a judgement. Orwell discusses this mental trick, called doublespeak, in his essay on the Principles of Newspeak, in Nineteen Eighty-Four. The key is that those who practice doublespeak do not think about an object at all: the object has no content except the judgement. Their thought halts just before reaching an object. In Politics and the English Language, Orwell translates a phrase from Ecclesiastes into Modern English: I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all. (p. 133) 3 Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science. trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Random House, 1974), §106. 3 And in Modern English: Objective consideration of contemporary phenomena compels the conclusion that success or failure in competitive activities exhibits no tendency to be commensurate with innate capacity, but that a considerable element of the unpredictable must invariably be taken into account. (p. 133) Though Orwell does not mention this, a writer of the modern version would not mean to say what the writer of Ecclesiastes does. Though he points in somewhat the same direction, the modern writer means “Objective consideration of contemporary phenomena...”that is, the indifferent, dim, bloodless message he gives. For him, the surprise and mystery of the encounter with his thought is entirely missing. Words are thought processes that carry him along without referring to objects. He is like a UN official who spends a solid hour every day signing documents that he has no time to read. Words have no content except insofar as they point to their content, but on their own, words seem to fit together without any gaps: language is systematic. Thus words seem linked necessarily. The language of Hegel is not the language of a man who encounters his meaning. He does not induce or compare, because he is inside his meaning. So he just speaks, like a prophet.4 His is the language, and conceptual language of necessity. Most of the philosophy since Hegel attacks this objective relation to truth. Foremost among these is Kierkegaard, who says that since it is you who know the truth, you must be aware of your relation to the truth. This implies that you are outside of it and cannot fully enter it. This is a relation of freedom, and of failure: you always remain outside of the relation to truth. Entering language for Orwell is like entering the truth as Hegel does. Once you do, it sweeps you from one word to the next, from one idea to the next in a chain of necessary links. This is what Orwell refers to when he says that people using orthodox language have turned themselves into machines (135-6). Introducing Thought to Language Orwell’s solution is analogous to Kierkegaard’s: thought is non-verbal, and when communicating, I should relate it to language as late as possible. We think wordlessly about concrete objects. Probably it is better to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations. Afterwards one can choose – not simply accept – the phrases that will best cover the meaning, and then switch round and decide what impression one’s words are likely to make on another person. (p. 138-9) He says ‘probably’ because language can correspond with its meaning. Language is an instrument for expressing, not for concealing or preventing thought (139), and as such it should adapt to thought, not the other way around. One’s meaning should choose the words (137-8). It should be clear, short, and therefore precise (138) to prevent extra words from smuggling in other meanings. A writer should invent images for the particular meaning he is trying to express (134). Though we tend to turn to language sooner when we think about abstract objects, we should try to avoid doing so (138). Abstract 4 Hegel would greatly dislike this comparison. 4 ideas have meaning, but, just like concrete ideas, if we surrender them to language, we stop thinking about them. Orwell is very sharp to notice this. Probably few people know what they mean when they say freedom, and even fewer when they say communism. Similarly, it is likely that few people really know what the words animal, or girlfriend mean. To write with this brevity and these images requires that a writer be conscious of the encounter between his meaning and his words. But at the same time, it requires that he meets his meaning vividly, in his thought or through his words. “When you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself” (139). The writer should look at his meaning from other perspectives. This encounter is ethical: a “comfortable English professor... cannot say outright, ‘I believe in killing off your opponents when you can get good results by doing so’” (136). Why can he not say it? Does he fear that the idea will be condemned by other people, or is he unable to encounter that idea himself without recoiling? Either way, if he does not cover up his meaning, a clear encounter with some other (a person or idea) would force him to be ethical. Orwell says that the misuse of language leads to a reduced state of consciousness (136): the writer or speaker is unaware of what he is saying, and his audience is unaware as well. Just as in the language of necessity there is no choice, neither is there judgement. This lack of freedom means the absence of ethics. If someone follows a law blindly, he is not ethical. Ethics implies a distance from the law, not in the sense that I transgress it, but in the sense that it is me who becomes ethical by choosing it. The law is not something that I can manifest in my life, so the law is not ethical. Insofar as I encounter and recognize the law as something different from myself, I can be ethical in my relation to it. But ethics does not necessarily require law, though it does require relation. If law can be likened to the doctrine of a culture or a political party, it should even be avoided: the concrete situation is rich with meaning that the law cannot take into account. But the law is useful as a kind of reminder to relate to others.5 The proper use of language, Orwell seems to imply, involves heightening one’s consciousness. Through language a man increases his consciousness in a sort of encounter with the meaning in the words, and the words themselves.6 What kinds of encounters are ethical? Is an ethical encounter the same as one that heightens one’s consciousness? Ethical Encounters Let us look at Orwell’s examples again: metaphor, false limbs, pretentious diction, and meaningless words. Metaphor describes a picture that one compares to the meaning the author is trying to convey. It does this comparison by analogy, by likening or drawing a parallel. To liken one thing to another is to put one in place of the other. This seems very difficult, perhaps a kind of 5 6 As such, it is related to memory. I will not speak here about the aesthetic side of ethics. 5 falsification, but we do it all the time.7 Badly used metaphor does not uncover a relation between things. False limbs make us, as it were, lose the rhythm because of too many drums. They prevent us from recognizing the relations between words. Pretentious diction distances us from a meaning by euphemism, which makes it seem objective, and impartial, and necessary. Meaningless words are usually so because of ambiguity: the object of thought is either absent, and the writer is being dishonest, or the word has many meanings. According to Orwell, what accounts for this misuse of language? “[Dying metaphors] are merely used because they save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves” (130). Laziness is the first reason that language is misused. If a writer is lazy he is probably also ignorant of misusing it. People turn verbs into phrases, and use pretentious diction to doctor up their prose, and to dignify their subject matter by “[giving it] an air of culture and elegance” (130-1). These people seem to be somewhat aware that there is an audience, but want to avoid it as much as possible. It is the same with writers who use meaningless words “in a consciously dishonest way” (133). Some use objectivesounding “phraseology... to name things without calling up mental pictures of them,” because they “cannot say outright, ‘I believe in killing off your opponents when you can get good results by doing so’” (136). This kind of dishonesty is also to evade of one’s readers. Some writers have turned themselves into machines, using language to anaesthetise their brains (136-7). Why would they do this? When they are machines, they are always right, they are in the truth. Nothing they write or do gives them reason to fear or to question. This is a kind of objective relation to their writing. We can collect these ways of misusing language into three frames of mind in which one can experience one’s writing. In the first, immediate experience of it, a writer never checks his language or his meaning from other points of view, and so is often ignorant of his misuse of them. If others disagree with him, he reacts with surprise, and cannot understand that they can disagree. We can call this the first-person experience of one’s writing. Characterized negatively, the second includes a probably dim awareness that one is writing to an audience, and the attempt to make one’s meaning and language avoid them. This is quite obviously unethical. Characterized positively, this way of experiencing one’s writing includes being aware of its audience, which means looking at it from other perspectives. We will call this the second-person experience of one’s writing. It requires a heightened awareness, and that one encounters one’s writing. It requires that we be ethical. The ignorance of the first-person perspective appears unethical only when considered in this second way of seeing. We will call it the second-person frame of mind. In the third, objective experience of meaning, the words do not really matter, and the writer ceases to pay attention to them. Besides, they flow easily and in long phrases, with many technical terms. The writer’s smallest thoughts might cover huge amounts of material. If someone disagrees with him he dismisses him as ignorant, or says the interests of his interlocutor prevent him from seeing the truth. This way of thinking is neither ethical nor unethical 7 Nietzsche uses this argument to refute the possibility of encountering reality in his essay On Truth and Lies in 6 until, by using the second-person frame of mind, his ideas are compared with what he supposes them to represent. We will call this the third-person frame of mind. Three Ways of Perceiving Literature generally uses these three points of view: first-person, second-person, and third-person. “I see the animal in the bushes” exemplifies the first-person way of perceiving. You look through a character’s eyes and experience things in an immediate, discontinuous (non-historical) and surprising way. It follows that it experiences a strange, negative freedom (there is no other to refuse it) and chance rather than necessity. It tends to involve self-interest (it cannot be self-less) and ignorance of others and oneself. “I see you watching me from the bushes” exemplifies the second-person awareness. It is the frame of mind of relation, the experience of continuity and discontinuity, ambiguity, love, and danger. This is the historical point of view: things are related, but neither necessary nor completely discontinuous. “Two people look at each other in the bushes” exemplifies the third-person way of experiencing. It is objective, and tends to be omnipotent (there is nothing de facto out of the scope of the narrator’s account), indifferent or detached, and see things as necessary rather than historical (math is necessary; it is not historical). Of course, these are caricatures of these literary devices, but they will help us talk about the relation between two people, which we will take as a model for an ethical encounter. If I approach someone in a first-person mindset, they are related to me, but I am not related to them. I am selfinterested. I can only identify with others in the way that a baby identifies with his mother: he sees no distinction between himself and anyone else; mom is just as much me as my arms and legs are.8 Someone in a first-person mindset cannot be ethical because he is unable to recognize other people. Respect, recognition, and consideration of others are all ethical activities that a baby cannot perform. A baby lives immediately in his eyes, and I can look at them with a feeling of complete safety. To the contrary, I cannot look an adult in the eye without being aware that he is hiding himself. The origin of deception, fear, interest, and desire is in this encounter in the second-person. If an adult does not hide himself, and his eyes show everything, he is either very immature, in love, or insane. In a second-person mindset, the same person is like another one of me. By ‘likening myself to another’ I relate to him by analogy, not by reducing him to myself. Indeed, I cannot reduce him to me. That is why he can be dangerous and attractive. I can identify with him, and put myself in his place. A second-person frame of mind is noticeably different from a first-person frame of mind: only certain kinds of monkey can identify when another monkey is in danger. In this mindset, I cannot be indifferent: I am related to the other, whether I am aware of it or not. I seek to understand him, and how we are related. I do this by relating to him and also dissociating myself from him. Horror movies and tragedies are an exercise in the second-person frame of mind: we feel something is coming, a Nonmoral Sense. 8 This does not mean that I have very much control over them. 7 dissociate ourselves from it, and at the same time relate ourselves to the character in the film or the play. Several times, while watching the last scene of Romeo and Juliet, I have heard people say to them “no! Don’t do it!” No matter how inappropriate it is, in this mindset we relate ourselves to other selves, feel and fear for them. So in this ability to liken oneself to another, we seem to have found a way of being ethical. In the third-person, one is (or thinks he is) outside of relations. One cannot be ethical in this mindset: ethics requires a subjective, personal encounter. Judges and courts are not ethical.9 Even if the law tries to inspire or regulate an ethical encounter, ultimately, it probably comes from an ethical encounter itself.10 The only goal of a court is to be as indifferent as possible in the application of the law. Thus a murderer can escape a prison sentence on a technicality. An ethical person cannot be indifferent. These correspond quite well with the reasons Orwell says writers misuse language. The proper use of language reflects a second-person frame of mind. A person must heighten his consciousness to be aware of another person reading or listening, to compare them through analogy with oneself and one’s writing. Perhaps metaphor’s uncanny power comes from likening-to-oneself. Fellow Creatures If we were writing all our thoughts down, when we think ethically, we might find ourselves using the second-person. We have found that this frame of mind is one in which you relate to other people by analogy or metaphor, that is, by likening yourself to them. In this way, you discover the other person as a self, like you. For Confucius, both likening-to-oneself and the “Golden Rule” are two sides of the same mindfulness. The “Golden Rule” has two formulations: 1) do unto others as you would have them do unto you, and 2) do not do to others what you would not want done to you. For Confucius, likening-to-oneself means also looking at a situation from all relevant perspectives.11 We often have sympathy for animals and even plants, so the second-person frame of mind is not restricted to an encounter with people. However, people tend to provoke it in us more often than do other living things. This provocation is how Orwell will improve language. Others are fellow creatures12, fellow living beings, for ethics must extend to all of nature. The habit of seeing human traits in animals is not necessarily a bad thing: the person who does it is in the right frame of mind, and values the animal at the same time. However, upon entering a first-person frame of mind, he should not take the similarities he found and use them to reduce the animal to himself. 9 This may explain why in theatre, movies, and literature, courts are often wrong, corrupt and generally full of intrigue. The authors must only rarely get their inspiration from real corruption. Rather, it seems contradictory that law and ethics are separate: I suppose, that the stories are an attempt to become conscious of the difference between law and ethics, and to reconcile them to one another. 10 c.f. William Desmond, Philosophy and its Others: Ways of Being and Mind (Albany: SUNY, 1990), chapter 4. 11 A.C. Graham, Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China (Chicago: Open Court, 1989), p. 29-30 12 “Fellow creatures” is a phrase of Ian Hacking. 8 What about using, or harming the fellow creature? Even if I am in this second-person frame of mind, I must surely be able to act unethically. This argument presupposes a ground of ethics outside of the individual. If one were to argue further, that no matter how they are done, certain acts never admit of being ethical, he would probably ground his argument in the way that his society understands the universe and its value, namely in its symbolic order. This argument would not contradict the idea of second-person mindfulness, but add to it, for your relationship with others has symbolic value. For an ancient Greek warrior, for example, it is good to die at the hands of a more powerful warrior. Evidently, in the past, many people thought that, in certain cases, hunters and warriors are ethically good. Leaving aside questions of the symbolic order of society, what makes an ethical hunter or warrior? In traditional cultures the hunt is usually sacred. Before taking his prey, the hunter will pray to it or thank it for offering its life. This is an ethical relationship: the ethical hunter recognizes, respects, and honours his prey. Even Kant’s categorical imperative recognizes, that at the same time as you treat other rational beings as ends in themselves, you may also be treating them as means. To be a warrior or a hunter you must be supremely ethical: you must be able to choose to die if you were in the position of the other creature. The ethical warrior and hunter never see the other as a victim, but as an animal with dignity that gives himself over to you. What if the other warrior is a weakling and does not want to die? It seems that likening oneself to others leads to two questions: 1) if you were in his position, would you want to die? In this case, no. 2) If he were in your position, would he kill you? In this case, yes. There is no infinite regress here, for he would be unethical were he to want to kill you and yet be unable to choose death for himself. The most ethical action, however, is to make him ethical.13 The ethical principle of likening oneself to others therefore gives us two questions to ask ourselves as criteria for an ethical act: 1) From other points of view, could I still approve of this action? 2) If others involved were in my position, would they choose this action? This is to determine action the wrong way about, however. What happens, and should happen, is that, being aware of the relevant points of view, I feel myself moved toward a certain action14, which I could then check by the two questions mentioned above. Most likely I would have already taken them into account. But when my instinct fails to do so, those rules can help me. This is a spontaneous, positive motion, quite unlike the compulsion of law, which is only required upon the failure of instinct. Law is unnecessary for a virtuous person. Nonetheless, in all encounters, one still must be ethical. Why is this? This kind of imperative to be ethical seems to echo the unconditional demand of Kant’s categorical imperative, but outside of any commanding law. 13 14 c.f. Homer’s Iliad The quasi-syllogism, in Graham, op cit. p. 29-30, and Appendix 1. 9 Self and Unconditional Demand Who is this self? In a sense there is no self in the immediate, first-person mindset, for there is no other. A baby is not a self yet. It is the same with the objective, third-person mind: it is impersonal, detached, and indifferent. Are you the side of a second-person relation that you cannot avoid? In a sense, others give this kind of self to you. You cannot experience yourself as a self until you can experience shame and pride. Hume argues that the idea of ‘self’ would originate in a scenario like this: while being applauded, the child asks himself “What are they clapping for? It is not my actions but me they are reacting to. What am I?” He then creates a self to receive the applause.15 I would add that how one takes compliments is a significant sign of one’s maturity. Kierkegaard locates the origin of the self in the fall into guilt. Before the fall, one could not be guilty (or feel shame), and suddenly one feels guilt and freedom at once.16 It is no accident that a Catholic confesses to someone, or feels sinful before God. I do not think that one must actually feel shame or pride in order to become a self, merely that one becomes capable of them when as one becomes a self. Both correspond with the second-person mind we are discussing: freedom is something you can only feel in this kind of awareness. This is an actor’s freedom.17 None of this ethics is rational or spiritual per se, though it could be both. My self is either given to me from the other18, or begins at the same moment that I can receive a gift, shame or pride from them. No matter which of the above is the case, in this frame of mind, I do not exist unless there is another.19 If there is no other, I revert to an immediate mind, a baby’s mind. The other is already in the self, and the self already in the other. Insofar as I am in that frame of mind, I must be a self, and there must be others. Thus the unconditional ethical demand is the demand that I recognize others, and liken them to myself. Only then can I be a self. This demand intertwines with desire for and fear of the other.20 These are all absent from the other two frames of mind that we have mentioned. However, it is not as faint a demand as it seems, for I can move from one kind of thinking to another, sometimes I do so involuntarily. Most people find it difficult to avoid desire and fear, which we said accompany the ethical frame of mind, and so its demand. Ethical philosophers have gone to great trouble to demonstrate that no matter where we begin, we must become ethical. It seems to me that these kinds of mindfulness coexist in a healthy person. Perhaps one simply learns to pay attention to one at a time. 15 David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature. ed. David Fate Norton and Mary J. Norton (Oxford: Oxford U. P., 2000), II.1.2, p.183. 16 Kierkegaard, The Concept of Anxiety. c.f. also Nietzsche, A Genealogy of Morals, Desmond, op cit., p. 166-8, and Robert Bly, Iron John: A Book About Men, in which he says the soul is made in the dark kitchen, that is, through work and failure. 17 c.f. Hannah Arendt, What is Freedom?, and The Human Condition. 18 c.f. Levinas, Totality and Infinity. Chapter C. 19 The self is highly contingent, and flows back and forth between the self and the other. Am I a person dreaming I’m a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming I’m a person? 20 Even in a sexual fantasy, what e.g. a man desires most is the other’s desire for him. 10 Judgement and Encounter: Heightened Consciousness To what extent does this describe Orwell’s idea of the ethical encounter? If it does, how does he suggest we incorporate it into the writing process? It is clear that he seeks a heightened consciousness in and through writing. This is possible, we remember, because I encounter what I think in my words, like a potter encounters his idea in clay, or a director in his actors. It is also clear that his central problem with the misuse of language, and thus the perversion of thought, is that it derives from and prevents me from encountering my meaning in an ethical way, which I have characterized as a second-person frame of mind. All of Orwell’s tips on writing are designed to make writers experience their language and meaning as clearly and directly as possible. Orwell says that “It is easier – even quicker, once you have the habit – to say In my opinion it is a not unjustifiable assumption that than to say I think... by using stale metaphors, similes and idioms, you save much mental effort” (134). Why would it be easier to spit out the phrase? In the phrase he mentions, judgement is suspended (not unjustifiable by whom?), rather than made. He gives many examples where an inflated style has in fact led to a suspension of judgement: “greatly to be desired”, “a consideration which we should do well to bear in mind” (131, and 137). It is obvious that there is no judgement when we ask who does and when, neither of which exist in the immediate or the objective style. I understand judgement to mean the act of situating a thing, of deciding its status and its relation to other things. It implies a personal commitment and confrontation with that judgement. It follows that, in the act of judgement one encounters and relates to what one wants to situate. A parent, who is going to discipline a child by spanking him, will sometimes say, “this hurts me as much as it hurts you.” This parent, who is in the ethical frame of mind, likens himself to the child, and the child to him. He accepts that if he were the child, he would want to be disciplined. It follows that it is hard to judge something. We can look at this difficulty in another way: it is difficult to encounter a thought, and much easier just to think. One cannot judge or relate things in the first-person point of view, but one can relate things using the objective point of view. Our comfortable professor of English can consider many things and then muddle out that political suppression is good. He has reasoned out his meaning but not confronted it. He merely stated that suppression is good, he did not judge so, for he did not relate himself to his statement. On the other hand, if he saw the same thoughts in the second-person frame of mind, he would recognize them, for they would stare back at him. In that frame of mind, in order to be able to assert that conclusion, he would have to be able to accept being suppressed. As Orwell says this sort of opinion on “Russian purges and deportations... can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face” (136). The metaphor of facing the argument is key for us here. An objective writer has no face, nor does a first-person writer. Shame, pride, and fear, however, 11 all happen in the face.21 Facing the argument means to con-front it, to be with and before it. Orwell implies that some people can face those arguments. In other words there are people who are like ethical warriors, who can encounter these brutal arguments ethically, and still choose them. Courage is a virtue. Our English professor may come to be the target of shame if he makes an unethical statement. This shaming would hopefully return him to the only frame of mind in which he can experience shame: the ethical mind. Hopefully, then he would encounter and be horrified at his own words. Shame is exactly what Orwell proposes as a solution to these problems of language: people should laugh or jeer bad language out of existence (138), or by jeering send useless phrases into the dustbin (140). The remedy is to induce from outside an ethical encounter with a writer’s meaning, if he is unable to be ethical on his own. The good writer should try to experience his meaning, then, once it is put in words, he should ...switch round and decide what impression [his] words are likely to make on another person. This last effort of the mind cuts out all stale or mixed images, all prefabricated phrases, needless repetitions, and humbug and vagueness generally. But... one needs rules that one can rely on when instinct fails. (p. 139) The writer should circle around his writing, like a potter circling his creation, and try to see it from other perspectives, through other people’s eyes. This is all done by analogy. But what does Orwell mean when he says that instinct fails? I suggest that it fails when it does not enter this secondperson mindfulness. The rules Orwell offers simply pare down one’s writing, which can make a writer encounter his meaning. But he mentions that “One could keep all of [these rules] and still write bad English” (139). The kind of English he means is unclear, even unethical English. What would have failed in this case? I offer that the bad writer still fails to encounter his meaning. Removing the dross from one’s language is to make it stand bare in front of you. With good language, “when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself"”(139). Orwell means that we should want to be in an ethical frame of mind. Only then can we think and write clearly, vividly, and ethically, and by doing so regenerate politics. Conclusion In Politics and the English Language, George Orwell argues that a writer should relate to his writing in a particular way. I have tried to show that this way of relating is only possible when a writer is in a second-person frame of mind. This kind of awareness is ethical. I have argued that neither the immediate nor the objective frames of mind can be ethical. Orwell criticises these, and implicitly promotes what I call the second-person awareness. The rules for good writing that he offers, and the technique of shaming a writer into writing good English intend to remind or force writers into the second-person awareness. He intends to restore it, and therefore ethics, to political writing. 21 “Nietzsche said that man was the animal with red cheeks.” Desmond, op cit., p. 167, note 10. 12 References Desmond, William. Philosophy and its Others: Ways of Being and Mind. Albany: State University of New York, 1990. Graham, A.C. Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China. Chicago: Open Court, 1989. Hume, David. A Treatise of Human Nature. Ed. Norton, David Fate and Mary J. Norton. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science. Trans. Kaufmann, Walter. New York: Random House, 1974. Orwell, George. Down and Out in Paris and London. London: Secker & Warburg, 1954. ----------------- Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Penguin, 2000. ----------------- Politics and the English Language in In Front of Your Nose 1945-1950. Ed. Orwell, Sonia and Ian Angus. London: Secker & Warburg. 13