An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Coal

advertisement

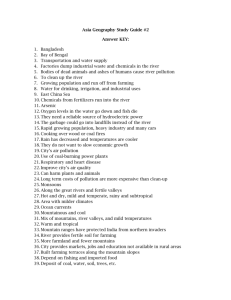

An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Coal-Burning Plant By: Kevin Conway, JoElyn Eppley, Nathaniel Gay and Sophia Turczynewycz Introduction: In our project, we intend to prove that Miami University has significantly altered the biodiversity of the watershed of the watershed of Four Mile Creek. We plan to use multiple methods of research and experimentation to prove our theory. Many readings pertain to the effect on rivers, streams and watersheds as a result of human interference and urbanization. The construction and expansion of Miami University near the Four Mile Creek is an example of urbanization of a previously undeveloped area. By examining how Four Mile Creek has changed since the conception of Miami, we will be able to determine what affect such urbanization has on waterways. 1 To narrow our project down, we plan to focus on the coal burning plant that sits behind Peabody Hall to research a specific aspect of Miami University. We plan to take an interdisciplinary approach in our study. We will study how the plant has affected Collins Run ecologically, why the plant was built and why it was built behind Peabody Hall. Our hypothesis is that the coal burning plant has had detrimental effects on Collins Run. The plant sits directly uphill from Collins Run. The plant’s parking lot pushes to the edge of the hill, and there is no barrier to trap loose particles of coal and coal dust. Shipments of coal are transferred to the plant via truck. The load of coal is poured into a large grate in the parking lot and shifts down to a storage facility underneath the lot. There is no barrier surrounding the grate, nothing to stop coal from spreading across the entire length of the lot. This loose coal can hypothetically run down the hill to Collins Run, especially in the event of a rainstorm. We hypothesize that the ground runoff of coal and coal dust particles from the paved area immediately surrounding the plant will have a detrimental effect on Collins Run, which lies downhill from the plant less than a half-mile to the east. We hypothesize that the presence of the coal particles will have a detrimental effect on the biological life of the area of Collins we will test. To establish to effects of the coal, we will also test an area of Harker’s Run, a creek similar to Collins Run but lies upstream from the plant and therefore is unaffected by its runoff. 2 Relevance: Books: Blount, Jim. The 1900’s: A Hundred Years in the History of Butler County Ohio. Past Present Press, 2000 This book presents a brief description of Butler County of the twentieth century. Through this book we will see how the town worked before the plant was built, and we will get a specific date of when the plant was built. Cannon, J.B. Fish protection at steam-electric power plants: alternative-screening devices. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, 1979. We will use this as a plan and resource when planning our own biodiversity testing, as well as when analyzing the results of our tests. 3 Cummins, Hays et al. WCP 261 v. 1 and 2 Western Rivers. Oxford Copy Shop, 2003 The reader feeds into the environmental justice aspect of our project, as well as basic background information in river and stream health/testing. Davis, Wayne T. and Noll, Kenneth E. Power generation: air pollution monitoring and control. Anne Arbor Science Publishers, 1976 This book will help us understand the scientific aspects of air pollution as well as understand the full effects and cycles one type of pollution can have on the whole environment. Diamant, Rolf. A Citizen’s Guide to River Conservation. Conservation Foundation, 1984 The title says it all. This book focuses on river conservation and how a simple citizen can take part in it. It will give us a clearer basis of understanding what full effect a single action can have on an entire watershed. Fraser, J.C. Determining Discharges for Fluvial Resources. 1975 This book deals with improving river environment for fish, measuring stream health and water resource development. It will help us develop a specified plan on how we will test Four Mile Creek. Havighurst, Walter. The Miami Years: 1809-1984. Oxford Printing Company, 1958 This book is an overview of Miami’s history written by someone who is a distinguished faculty member of the University. It shows the growth and expansion of Miami from underdeveloped land to a public ivy. It will give us a clearer understanding of how Miami University and the Four Mile Creek functioned before the plant was built. Hover, John C. et al. Memoirs of the Miami Valley. Robert O. Law Company, 1919 This book is a history of the Miami Valley broken up into different counties, including Butler 4 County. Again, this book shows the development and growth of the Miami Valley. It will give us a clearer understanding of how the Four Mile Creek and Miami University functioned before the plant was built. Maxwell, J.D. Economics of nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides, and ash control systems for coalfired utility power plants. U.S. EPA, Air and Energy Engineering Research Laboratory, 1985 This book is an incredible aspect to our project. Not only does it cover the economics of coalfired utility power plants, but it specifically covers the issue of sulfur, which is our main scientific research aspect. Migel, Michael J. The Stream Conservation Handbook. Crown Publishers, 1974. This book focuses on stream conservation, fish habitat improvement and fish stocking. This book will give us a better understanding of how Four Mile Creek functions. Milligan, Jack D. Effects of coal-ash leach ate on ground water quality. 1980 This will be helpful in examining the environmental aspects and ground water pollution from coal-fired power plants. Myers, Robert H. Collection of Oxford Information. The Chamber, 1971-1983 This provides information on Oxford, including a booklet on how Oxford is an “ideal place to live, work, play, and enjoy.” This discussing quality of life, which could easily be influenced by the fact that there is a coal-burning plant in Oxford. 5 Noyes, Robert. Cogeneration of steam and electric power. Noyes Data Corp. 1978 This book will give us an idea of the general workings of a steam/ coal-burning plant including emissions and possible contaminations to surrounding environments. Sanders, Randall E. A Guide to Ohio Streams. The Ohio Chapter of American Fisheries Society, 2000 This book is a brief reference to Ohio’s streams and watersheds. It will give us a better understanding of Four Mile Creek and its surrounding watershed. Shannon, Robert H. Handbook of Coal-Based electric power generation: The Technology, Utilization, Application and Economics of coal for generating electric power. Noyes Publications, 1982 This book will be helpful in learning the basics in coal burning. Websites: Clearwater News and Bulletin http://www.clearwater.org/news/powerplants.html 24 April 2003 Enviro Health Action. “Air Pollution and Health” http://www.envirohealthaction.org/pollution/power_plants/ 26 April 2003 Miami Conservancy State of Water Resources, “Overview of the Great Miami River Watershed” http://www.miamiconservancy.org/Water_Resource_Monitoring/Water_Study_Reports/02State WtrRsrcs8-22.pdf This site offers various information on the Great Miami River Watershed. 6 Miami University Art Museum, “Four Mile Creek and Bonham, Oxford, Ohio, 1860” http://www.fna.muohio.edu/amu/full/barrow.htm This site displays an oil painting by Charles Barrows depicting Four Mile Creek. Miami University Natural Areas http://zoology.muohio.edu/naturalareas/#c11 This site gives information on the natural areas surrounding Miami University including Four Mile Creek and Western Woods. National Register of Historic Places, “Ohio Ð Preble County” http://www.nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com/OH/Preble/state.html This site provides information on what parts of Four Mile Creek have been established as having historical significance. Sewage Treatment http://www.cas.muohio.edu/~stevenjr/sewagetreatment/ This site goes over the importance of sewage treatment plans and how it all works. The Delaware Indian Road http://homepages.rootsweb.com/~maggieoh/Migrate/merle2.htm This site describes Indian roads and migration routes that pass through Four Mile Creek. Three Valley Conservation Trust http://www.3vct.org This is the official website for an organization that tries to preserve the natural wilderness of the Three Valley area. Union of Concerned Scientists, Citizens and Scientists for Environmental Solutions http://www.ucsusa.org/CoalvsWind/c01.html 23 April 2003 7 Varying Pollution Through Human Influence: Four Mile Creek, Oxford, Ohio http://jrscience.wcp.muohio.edu/nsfall02/progress02Articles/VaryingPollutionThroughHu.html This site shows past research and studies done on Four Mile Creek, and is similar to our project in studying human influence on Four Mile Creek. Our research relates to the larger question of how urban development effects "natural areas". Miami University represents an area of substantial development where there had previously existed wilderness. Interdisciplinary Approach: The science aspect of our project will focus on objective monitoring of Four Mile Creek. It is commonly accepted to study the biodiversity of a creek system to determine its health, and we plan to focus on the organisms that rely on Four Mile Creek for their survival. In doing this we will be able to establish the present status of Four Mile Creek. We plan to focus on the biodiversity in and along the creek. In regards to the social sciences, we will examine why the plant was built on Western, researching political reasons. For humanities, we will study the history of the plant, Western College, and the Miami University in general. Research Design: We scientifically monitored the stretch of Four Mile Creek that lies directly down hill from the plant. This entails an evaluation on biodiversity (the monitoring of plant and animal life), examination of geomorphological health. We also performed the same studies an area of 8 Harpers Run, a nearby creek that shares the same basic biological and geological qualities of or testing area of Four Mile Creek, but lies upstream from the plant and therefore is free from any possible run-off of coal particles. This section of Harker’s Run acted as a control sample in our experiment. Using it as the norm, we judged the disturbance to Four Mile Creek. We interviewed Curt Ellison, an expert on the history of the Western College, to establish the historical context of the plant, determining when the plant was built, who initiated its construction and why the plant was built at its specific location on Western Campus. Material and Methods: For general background information on coal burning plants, we researched the Internet for sources on how coal-burning plants affect the environment, as well as how they affect society. These sources include Clearwater News and Bulletin, The Union for Concerned Scientists Website and the EnviroHealth Action websites. To monitor the streams, we observed both Collins Run and Harker’s Run to see the difference between one stream that was by the coal-burning plant and one stream that was far away from the plant. To take images of these comparison, we brought along a digital camera. We also used the digital camera to take pictures of the coal-burning plant that sits behind Peabody, right uphill from Collins Run. Nathaniel captured some great images of a truck dumping coal onto the parking lot, as well as other images of the plant along the creek. We used our background knowledge in monitoring stream health from our WCP 261 Rivers: An Interdisciplinary Study class in assessing the health of Collins Run and Harker’s Run. We also went fish shocking to collect data on the biodiversity of the stream. We also used past studies and research done on Collins Run and Harker’s Run to compare data. 9 We interviewed Curt Ellison to get a good grasp on the background, history and uses of the coal-burning plant that sits behind Peabody. We learned why the plant was built on Western and not somewhere else, as well as other valuable information. Results: The Coal Burning Plant in the Context of the History of Miami University and Western College The coal burning plant behind Peabody Hall on Western Campus was built soon after the acquisition of Western by Miami University in 1974. One of the major considerations in obtaining the campus was room for the expansion of the university, which had been growing steadily since the end of World War II. Oxford was at one time “boasted not less than five separate institutions of higher learning” (Blount 13). Several of those institutions have been observed into the greater Miami University as it grew. One option for accommodation the growth was to expand westward into the town of Oxford. The other was to expand eastward into undeveloped woodland and eventually the Western College for Women. The latter option was chosen, and new construction of buildings took place on the ever-expanding eastern edge of the Old Miami. However, this exposed a rather unsightly part of the university’s physical facilities: the old coal burning plant. The old plant stood at what is now the parking lot of Gaskill Hall, near what is now Spring Street. Before the expansion of residential and academic buildings reached it, the plant was tucked away out of sight within the wooded land. It was an “eyesore” 10 and did not match well with the newer buildings or the clean-cut image Miami wanted to express. It is small wonder that the university moved so quickly to construct a new plant on the Western Campus. There, it would be out of sight, at least to those on main campus. The construction was part of a larger transformation of Western Campus that took part after its acquisition. The first Miami buildings that were built on the campus were Bachelor Hall and Havighurst Hall, which covered the beloved apple orchard of the old Western Campus. Next came the razing of Alumnae Hall, which stood in what is now the field between Peabody Hall and Boyd Hall. The hall served as classroom space for the Western College for Women, and housed many other important activities. It was a large, impressive looking building that was key to the independence of Western. Claiming that the renovations that Alumnae needed were too expensive, Miami tore it down to save money. However, debate still exists as to the real reasons for Alumnae’s destruction. While it is true that the building did need renovations (In Miami Years 1809-1984, Walter Havighurst calls the building “decrepit”) the claim that Miami could not afford the process is weak, especially considering the amount was spending to acquire the whole campus and construct multiple new buildings on it. Also, the architecture of Alumni was radically different from the neo-Georgian red brick architecture of almost every building on main campus. Miami could have disposed of Alumni in order to maintain a unified architectural image. The destruction of Alumni could represent disrespect for the Western Campus by the larger university. As stated above, the campus was acquired not for academic reasons, but rather for expansion room. Western was (is?) seen for utilitarian purposes, which lead to the construction of the coal burning plant right behind the most important building on the campus. 11 This construction did not go unchallenged by the Western faculty: as most protest as possible was raised against the plant, but it was little good. The same people had protested the construction of Bachelor and Havighurst Halls, and those building still received the go-ahead. The coal plant was just another loss for the attempt to preserve the old Western. The plant entailed more construction on the campus. All sidewalks were torn up and replaced with hollow ones through which pipes carrying steam from the plant could reach main campus. If one looks through the grates on the Western sidewalk (one grate lies between Peabody and Boyd Halls) one can see these pipes. Also, the metal bridge directly down the hill from the front of Peabody Hall (the walkway that runs by the Freedom Summer Memorial leads to it) was constructed to cover major piping. The expansion of Miami University on to the Western Campus continues today. After the first round of buildings, more Miami institutions were plopped down on “the other side of “Patterson.” The art museum is a testament to this. (This happens to be another architectural controversy: the benefactor of the museum attached a clause to the donation stating that the building must be built in a non-traditional style of architecture. This meant no red bricks. Stuck with a building that did not follow the unified image of Miami, it is thought by some that the university tucked it away on Western as to make it less visible.) The most recent example of this is the newly opened childcare center, which sits next to Thompson Hall. More buildings are in the works, such as a whole academic quad planned for the wooded area behind Boyd Hall. While it is uncertain whether or not the quad will actually be built, the message is clear: Western Campus will change according to the needs of Miami’s expansion. 12 Background Information of Coal Burning Plants http://www.ucsusa.org/CoalvsWind/c02c.html# Fossil fuels are America’s number one source of energy, accounting for 85 percent of the current U.S. fuel use. (http://www.envirohealthaction.org/pollution/power_plants/ 26 April 2003) 13 Coal accounts for 54 percent of U.S. energy use. Most of the coal and fossil fuels being used are burned by power plants (or coal-burning plants). A typical plant burns 1.4 million tons of coal each year. (http://www.ucsusa.org/CoalvsWind/c01.html 23 April 2003) These fossil fuels and coal are not a long-term solution to solving our energy needs, and they cause a large number of health and environmental problems. According to Enviro Health Action, there are more than five hundred major coal burning plants in the United States today, and the majority of them are very old. (http://www.envirohealthaction.org/pollution/power_plants/ 26 April 2003) Coal-burning plants emit so much air pollution. They are one of the leading sources of the air pollution that is adversely affecting our health, as well as the health of the environment. Coal burning plants are the main source of 67 percent of the total emissions of sulfur dioxide in the United States, 1/3 of U.S. mercury pollution, 1/3 of the nation’s nitrogen dioxide and 40 percent of carbon dioxide emissions. (http://www.envirohealthaction.org/pollution/power_plants/ 26 April 2003) Even when the most modern technology coal burning plants use low-sulfur coal, they are still one of the leading single sources of acid rain, which has profound effects and changes on forest ecology. Other emissions from coal-burning plants include arsenic, beryllium, cadmium, chromium and nickel. (http://www.clearwater.org/news/powerplants.html 24 April 2003) Besides air pollution, coal-burning plants also contribute to water pollution, affecting the biodiversity that surrounds them. Coal-burning plants use the water around them for cooling. When water is taken in, many fish species and their eggs or larvae get trapped. Many of them die or are injured in this process. (http://www.ucsusa.org/CoalvsWind/c02b.html 23 April 2003) The cooling water is discharged back into the lake, river or stream that it was taken from. When this happens, thermal pollution may occur, affecting the wild life that is living in the water. The hot 14 water can decrease fertility in the fish as well as raise their heart rate. (http://www.ucsusa.org/CoalvsWind/c02d.html 23 April 2003) In the winter, this hot water creates ice-freeze pockets, which many species are attracted to, and then they become trapped when the water flow slows down or even stops. In the summer, the hot water from the plant may add eutrophication to the water, leaving the fish and other wildlife without oxygen, choking them. The cooling water from the plants also contains heavy metals and chlorine, which have a negative effect on the biodiversity of the body of water. (http://www.clearwater.org/news/powerplants.html 24 April 2003) Other than water pollution and air pollution, coal-burning plants also affect the fish that live in the water. Tiny fish eggs, fish larvae and small fish as well as other invertebrates are adrift in the water, and many of them are very vulnerable to the intake of power plant cooling water intakes. These animals are often injured or killed by the passage through the plant’s cooling system. According to a Clearwater News and Bulletin fact sheet, “In certain species, reports document up to 60% mortality in a given year’s newborn fish stock due to power plants” (http://www.clearwater.org/news/powerplants.html 24 April 2003). Coal from the power plants is often stored and left in uncovered piles outside of the plant. Dust from these uncovered piles is blown everywhere, settling on houses, yards and the rest of the environment as well as affecting our lungs. When it rains, runoff from these piles is created and flows right into land and water, contaminating them. (http://www.ucsusa.org/CoalvsWind/c02a.html 23 April 2003) Power plants not only have an effect on environmental issues. They also have an effect on societal and cultural issues as well. Structurally, power plants are huge industrious buildings, with large smoke stacks and other structures that make everything around them look small. Because they are so huge, they can be seen from far away, harming view sheds that are valued by 15 the surrounding areas. Homes and other sites that are close in proximity to the plants are devalued in historical significance (if they have any) because of the plants insufficient use, size and architecture. Each new power plant that is built provides more power to the marketplace. This power is “artificially cheap” because costs for environmental, health and infrastructure issues are not accounted for in the price of fuel. These costs, called externalities, are paid for by society. These externalities include conflicts over seas with oil rich nations. Because the energy is readily available from these fossil fuels and coal being burned by these plants, society has little incentive to find a more energy sufficient and environmentally sound way to suit our energy needs. “Feeding short-term demand by increasing fossil fuel production does not provide a longterm solution” (http://www.clearwater.org/news/powerplants.html 24 April 2003). Power plants are often built in poor communities, or communities of color and certain “sitting laws” do not require the plant to provide a statement on environmental impact as well as overriding development designs and planning. Plants also need water for cooling, hence them being built by lakes, creeks and rivers. Comparison of Fish Samples in Collins Run and Harker’s Run We used information from Hays’ website for our data on fish b biodiversity. For Collins Run, we used the fish shocking that went on this year. For Harker’s Run we had to use information from the fish shocking last year. In Collins Run, the presence of Moxostoma duquesnei, Common name Black Redhorse, indicates that water quality is high enough to sustain 16 this pollution sensitive fish. Only one of these species, although, indicates that the fecundity of this fish is quite possibly in danger and the water quality of Collins Run Stream needs to be protected to prevent endangerment. In fact, there were only three types of fish found that are indicative of high water quality. The other two are Micropterus dolomieui, or the Smallmouth Bass, and Notropis buccatus, common name Silver Jaw Minnows. Prevalence of a large fish, Catostomus commersoni, White Suckers, indicates the possibility of high pollution and low water quality. With only five present, it is hard to determine whether the water quality is high or low. Because this type of fish was found in this area, we can see it is an area that the White Suckerfish can thrive in, however this is not a concrete indicator of low water quality. The most prevalent fish found, Campo stoma anomalum, common name Central Stonerollers, could tell us a lot about the water quality in Collins Run. They are known as a low water tolerant fish. There were three times as many Central Stonerollers than any other kind of fish. Because of there domination in this habitat, they are a good indication of the water quality here. All in all, the data found in Collins Run clearly shows the prevalence of highly tolerant fish, or fish that can strive in low quality streams. The slight presence of high water quality fish however shows that Collins Run is not overridden with pollution or poor stream qualities. The most common fish found in Harker’s Run is the Semotilus atromaculatus, common name Creek Chub. This fish is categorized as tolerate of low water quality. Its dominating presence is not a good sign for the health of Harker’s Run. However, unlike Collins Run, the difference between this fish, the most common found, and the next is a small gap. The second 17 most dominant fish, Campostoma anamalum, common name Central Stonerollers, were by far the most dominate in Collins run. They too are fish that thrive in low water quality streams. The Bluntnose Minnow, or the Pimephales notatus, was another fish found quite frequently in Harker’s Run. It is also tolerant of low water quality. The fact that the three most commonly found fish in Harker’s Run are all low water quality fish says something about the health of this stream. This stream is obviously not of good water quality. In fact there were only two species found in the Harker's Run sampling that are high water quality fish. These were the Catostomus commersoni, common name White Suckers, and the Notropis buccatus, common name Silver Jaw Minnows. There were a total of 11 fish found from these two species. Discussion and Conclusion When comparing the difference between Harker’s Run and Collins Run, many observations can be made. Harker’s Run and Collins Run had approximately the same number of low water quality species. While Harker’s Run had fewer high water quality species, more high water quality fish were found. Both streams had 15 species found during their fish shockings, however Harker’s Run had many more fish caught. Both seemed to have a noticeable distribution of species between low quality and high quality tolerant fish. The conclusions we are able to draw from this data are small. The differences between the two data sets are too close to draw any reasonable distinctions between them. However, the data was notably imprecise due to the amateur status of the students that completed the testing and compiled the findings. The students of this class missed many of the fish that were shocked 18 and washed downstream. Missing many fish species and numbers added up over the two hour period and the missed fish numbers were compelling enough to draw notice. We feel that if any compelling and precise data were to be recorded, it would have to be by professionals in the study of fish diversity and testing of streams. Collins Run appears to be quite healthy, despite the intensive development of the watershed. It flows by a Wal-Mart, McDonald’s, and a coal plant, yet no precise data was discovered that could link the Coal Plant directly to the effect on biodiversity of Collins Run. Despite this finding, we still believe that a more accurate testing on the stream’s integrity would reveal that the Coal Plant on Western Campus does, in fact, damage the stream and the integrity of the Four Mile Watershed. We come to this conclusion because of the fact that the Coal Plant lies directly uphill of Collins Run with a clear-cut path directly to the stream. Our data proves that the dust released from the dumping of the coal removes car paint and most definitely effects the nearby environment adversely. Coal sludge is washed downhill from the plant to the only body of water nearby, Collins Run. Although our findings cannot pinpoint any direct evidence to the destruction of Collins Run by the Coal Plant, it is our belief that it does, in fact, adversely affect the watershed biodiversity. Works Cited Blount, Jim. (2000). The 1900’s: 100 Years in the History of Butler County, Ohio. Past/Present/Press: Hamilton, Ohio. Clearwater News and Bulletin http://www.clearwater.org/news/powerplants.html 24 April 2003 Cummins, Hays. http://jrscience.wcp.muohio.edu/html/index.html 20 April 2003 19 Ellison, Curt. Personal Interview with Nathaniel Gay. 10 April 2003. Enviro Health Action. “Air Pollution and Health” http://www.envirohealthaction.org/pollution/power_plants/ 26 April 2003 Havighurst, Walter. (1984). The Miami Years 1809-1984. GP Putnam’s Sons; New York. Union of Concerned Scientists, Citizens and Scientists for Environmental Solutions http://www.ucsusa.org/CoalvsWind/c01.html 23 April 2003 20