File

advertisement

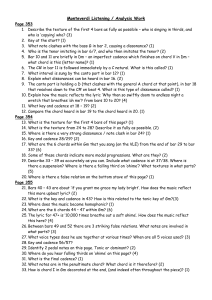

Cadences Functional Harmony From about 1680 until well into the 19th Century (and in much later music as well) harmony was functional – that is, an important function or purpose of the chord progressions used was to establish and maintain a key. We can divide individual chords into three main groups according to their functions: The Tonic Group Chord I Chord vi. e.g. A C C E E G Chord I has the tonic of the scale as its root and is normally the only chord considered stable enough for a whole piece to end on. The Dominant Group Chord V Chord V7 Chord vii e.g. G G B B B D D D F F All of these chords contain note 7 (in this case B), which has a powerful tendency to rise to 8, hence the name ‘leading note’. It quite literally leads back to the upper tonic. The Subdominant Group Chord IV Chord ii Chord ii7 e.g. D D F F F A A A C C 1 Activity 1 Using the above layout as a guide, work out the tonic group, dominant group and subdominant groups chords for the following keys. a) G Major Tonic Group Roman Numeral I Chord Name G Major Notes G B D Chord Name Notes Chord Name Notes Chord Name Eb Major Notes Eb G Bb Chord Name Notes Chord Name Notes Dominant Group Roman Numeral Subdominant Group Roman Numeral b) Eb Major Tonic Group Roman Numeral I Dominant Group Roman Numeral Subdominant Group Roman Numeral 2 The Perfect Cadence When a phrase ends with a V-I chord progression this is called a perfect cadence. In functional harmony it is by far the most widely-used type of cadence. Activity 2 Mark examples of the progression V-I in the following extract: Approaching a Perfect Cadence Look at bars 3-4 of the above extract. You will see that the V-I perfect cadence is preceded by chord iib, which is one of the subdominant group of chords. In fact, any of the chords from that group makes an effective approach to a perfect cadence. Many phrases that conclude with a perfect cadence end with the following three chords: A chord from the subdominant group, then A chord from the dominant group (usually V or V7), and finally Chord I from the tonic group. Activity 3 Identify and label the chords marked with * in the following extracts: 3 Activity 4 Here are the final phrases from four Christmas carols, all ending on the tonic. Name the key of each and add chord symbols at the places marked *, choosing an approach chord from the subdominant group followed by a perfect cadence in every case: The Cadential 6/4 The perfect cadence can also be approached from chord Ic. Although this is a very common approach, Ic is not really a fully independent chord but more of a decoration of chord V, with which it shares the same bass note: C Major Ic = V = G G C B E D For that reason, Ic is often used between an approach chord from the subdominant group and the actual perfect cadence, in such patterns as IV – Ic – V7 – I. 4 In the example below you can see that: E in chord Ic moves down by step to D in chord V C in chord Ic moves down by step to B in chord V Both chords have G in the bass. In terms of intervals above the bass, we hear a 6th falling to a 5th, and a 4th falling to a 3rd. This 6/4 to 5/3 movement is the essence of the Ic-V progression. When chord Ic is used in this cadential position it is often called the cadential 6/4. Activity 5 Add notes on the treble stave of these two passages to complete chords Ic and V in the places indicated. Each chord requires two more notes. Check that the notes in each of your Ic chords fall by step to the following V chord and that the interval between them and the bass note (ignore the octave) is 6/4 followed by 5/3. (See the above example for help). 5 Interrupted Cadences If you replace chord I in a perfect cadence with some other chord, you create an interrupted cadence – so called because it the expected progress of the music to the tonic. It is sometimes used as a ‘delaying tactic’, creating the expectation that a perfect cadence will soon follow. Play the following example (in pairs if necessary) and listen how the interrupted cadence affects the expected perfect cadence to the tonic: Interrupted cadences frequently end with chord vi, as here but any chord that creates an effective surprise (e.g. IVb) is possible. In a minor key chord VI is major, which makes the effect of an interrupted cadence more arresting. In general, remember that interrupted cadences are far less common than perfect cadences. Exercise 6a In the following extract, label the chords and fill in the missing treble note and bass note to end first with chord I, then chord vi. Play each example. # 6 Exercise 6b Using the same piece but transposed to G minor repeat the task above but this time fill in the notes to end on first chord VI and then a diminished 7th chord. Play each example. Imperfect Cadences The progression V-I can be used almost anywhere – at the beginning, middle or end of a phrase. At the end of a phrase it is called an imperfect cadence. Imperfect cadences must end with chord V, but they do not need to have chord I as the first chord. Some examples of imperfect cadences include: ii-V iib- V ii7b – V. Plagal Cadences The subdominant chord (IV) is widely used before and after chord I. Chords IV – I, when used at the end of a phrase, make a plagal cadence. A plagal cadence can end a phrase because its final chord is I but is used far less frequently than the perfect cadence. Year ago it was common in church to sing ‘Amen’ to a plagal cadence at the end of a hymn and for this reason, people still occasionally call it an ‘Amen’ cadence. Cadence Summary Perfect: V(7) – I Imperfect: and chord to V Interrupted: V(7) to any chord except I (often V(7) – vi) Plagal: IV – I 7 Exercise 7 – Last one I promise! Play each of the following extracts. In each case identify the key and the chords marked *, and identify the cadences formed by these chords. 8