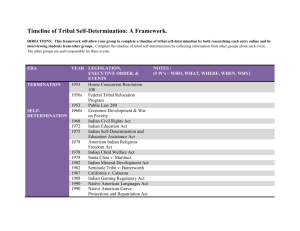

federal indian law

advertisement