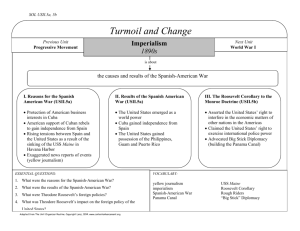

extra readings on the causes of the Spanish

advertisement

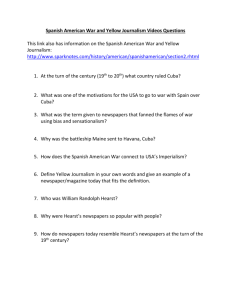

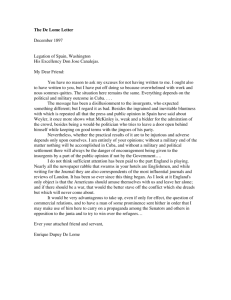

Name: __________________________ Date: ________________ Section: 11.1 11.2 11.3 (circle one) U.S. History II Causes of the Spanish-American War Do Now Use last night’s homework, if necessary, to answer the following questions. (Phrases, sentence fragments, or bullet-pointed lists are fine – but you must use your own words!) 1. Who governed Cuba in the 1880s? 2. Why did Cubans revolt against the Spanish, and how did this revolt affect American interests? 3. How did Spain respond to the revolt in Cuba? How did Americans react to the Spanish response? 4. What was the De Lome letter? Exit Ticket Summarize three causes of the Spanish-American War, in 1-2 complete sentences each, in your own words. Cause 1: Cause 2: Cause 3: 8 Awesome 7 Solid 6 Getting there 5 Needs serious work 4 Missed the point completely Presentation: Causes of the Spanish-American War In this class period, you and a small group of classmates will be responsible for researching one cause of the Spanish-American War. You will use the sources listed below to produce a small poster (I’ll project it using the document camera) and deliver a three-minute presentation in front of the class. Poster and Presentation Requirements Your poster and presentation should convey the following information: □ Basic factual information: What happened? When? Who was involved? □ How did it contribute to the American decision to declare war on Spain? □ Why was your cause not sufficient, on its own, to cause the US to declare war on Spain? □ Bonus points for an artistic representation of your cause Your presentation should last three minutes and include all members of your group. You should be ready to take questions from other students at the end of your presentation. Sources You will use the following sources to prepare your poster and presentations. Unless otherwise noted, all the sources listed below can be found in this packet. Support for imperialism in general: o Albert Beveridge, “The March of the Flag” (coursepack, p. 37) o Josiah Strong, “Our Country” (coursepack, p. 38) Reconcentration camps: o “Life in the Reconcentration Camps” o “What Senator Proctor Saw in Cuba” Yellow journalism: o U.S. Department of State, “U.S. Diplomacy and Yellow Journalism, 1895-1898” o “Spaniards Search Women on American Steamers” The De Lome letter: o The De Lome Letter (coursepack, pp. 47-48) o Library of Congress, “Enrique Dupuy de Lome” In addition, everyone should use last weekend’s homework (“The Spanish-American War, Part 1”) to help them understand their assigned cause. Life in the Reconcentration Camps This anonymous note was included in a telegram sent by Fitzhugh Lee, U.S. Consul-General in Havana, Cuba. A consul-general is a government official who is responsible for protecting U.S. citizens and promote American interests in a foreign city. SIR: . . .[W]e will relate to you what we saw with our own eyes: Four hundred and sixty women and children thrown on the ground, heaped pell-mell as animals, some in a dying condition, others sick and others dead, without the slightest cleanliness, nor the least help. . . . . . Among the many deaths we witnessed there was one scene impossible to forget. There is still alive the only living witness, a young girl of 18 years, whom we found seemingly lifeless on the ground; on her right-hand side was the body of a young mother, cold and rigid, but with her young child still alive clinging to her dead breast; on her left-hand side was also the corpse of a dead woman holding her son in a dead embrace . . . The circumstances are the following: complete accumulation of bodies dead and alive, so that it was impossible to take one step without walking over them; the greatest want of cleanliness, want of light, air, and water; the food lacking in quality and quantity what was necessary to sustain life . . . From all this we deduct that the number of deaths among the reconcentrados has amounted to 77 per cent. “What Senator Proctor Saw in Cuba” This illustration claims to show what Senator William Proctor of Vermont saw on a trip to inspect reconcentration camps in Cuba. U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, “U.S. Diplomacy and Yellow Journalism, 1895-1898,” Milestones: 1866-1898, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/yellow-journalism. Yellow journalism was a style of newspaper reporting that emphasized sensationalism over facts. During its heyday in the late 19th century it was one of many factors that helped push the United States and Spain into war in Cuba and the Philippines, leading to the acquisition of overseas territory by the United States. The term originated in the competition over the New York City newspaper market between major newspaper publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst. At first, yellow journalism had nothing to do with reporting, but instead derived from a popular cartoon strip about life in New York’s slums called Hogan’s Alley, drawn by Richard F. Outcault. Published in color by Pulitzer’s New York World, the comic’s most well-known character came to be known as the Yellow Kid, and his popularity accounted in no small part for a tremendous increase in sales of the World. In 1896, in an effort to boost sales of his New York Journal, Hearst hired Outcault away from Pulitzer, launching a fierce bidding war between the two publishers over the cartoonist. Hearst ultimately won this battle, but Pulitzer refused to give in and hired a new cartoonist to continue drawing the cartoon for his paper. This battle over the Yellow Kid and a greater market share gave rise to the term yellow journalism. Once the term had been coined, it extended to the sensationalist style employed by the two publishers in their profit-driven coverage of world events, particularly developments in Cuba. Cuba had long been a Spanish colony and the revolutionary movement, which had been simmering on and off there for much of the 19th century, intensified during the 1890s. Many in the United States called upon Spain to withdraw from the island, and some even gave material support to the Cuban revolutionaries. Hearst and Pulitzer devoted more and more attention to the Cuban struggle for independence, at times accentuating the harshness of Spanish rule or the nobility of the revolutionaries, and occasionally printing rousing stories that proved to be false. This sort of coverage, complete with bold headlines and creative drawings of events, sold a lot of papers for both publishers. The peak of yellow journalism, in terms of both intensity and influence, came in early 1898, when a U.S. battleship, the Maine, sunk in Havana harbor. The naval vessel had been sent there not long before in a display of U.S. power and, in conjunction with the planned visit of a Spanish ship to New York, an effort to defuse growing tensions between the United States and Spain. On the night of February 15, an explosion tore through the ship’s hull, and the Maine went down. Sober observers and an initial report by the colonial government of Cuba concluded that the explosion had occurred on board, but Hearst and Pulitzer, who had for several years been selling papers by fanning anti-Spanish public opinion in the United States, published rumors of plots to sink the ship. When a U.S. naval investigation later stated that the explosion had come from a mine in the harbor, the proponents of yellow journalism seized upon it and called for war. By early May, the Spanish-American War had begun. The rise of yellow journalism helped to create a climate conducive to the outbreak of international conflict and the expansion of U.S. influence overseas, but it did not by itself cause the war. In spite of Hearst’s often quoted statement—“You furnish the pictures, I’ll provide the war!”—other factors played a greater role in leading to the outbreak of war. The papers did not create anti-Spanish sentiments out of thin air, nor did the publishers fabricate the events to which the U.S. public and politicians reacted so strongly. Moreover, influential figures such as Theodore Roosevelt led a drive for U.S. overseas expansion that had been gaining strength since the 1880s. Nevertheless, yellow journalism of this period is significant to the history of U.S. foreign relations in that its centrality to the history of the Spanish American War shows that the press had the power to capture the attention of a large readership and to influence public reaction to international events. The dramatic style of yellow journalism contributed to creating public support for the Spanish-American War, a war that would ultimately expand the global reach of the United States. “Spaniards Search Women on American Steamers” This drawing by Fredric Remington was published in a newspaper owned by William Randolph Hearst, a famous yellow journalist, in 1897. It allegedly shows women being stripsearched by Spanish government officials as they prepared to depart Cuba on an American ship. “Enrique Dupuy de Lome: 1851-1904,” The World of 1898: The Spanish-American War, Library of Congress, 2011, http://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/1898/dupuy.html. Born in Valencia, Spain, Enrique Dupuy de Lôme came from a family of French origin who settled in Spain. After completing his legal studies at the University of Madrid in 1872, Dupuy de Lôme entered diplomatic service. During the following years he served in a variety of posts including Japan, Belgium, Uruguay, Argentina, the United States, Germany, and Italy. In 1892 he was named Spanish Minister to the United States. Although the years of President Grover Cleveland's second term (1892-1896) were relatively peaceful for the Spanish Minister, they were marked by increasing tension as Cleveland attempted to maintain a policy of neutrality toward the 1895 Cuban war of independence. When President William McKinley took office in March 1897, he was determined to reverse his predecessor's policy. He decided to renew the customary courtesy visits of U.S. warships to Havana and ordered that the brand-new battleship Maine be sent as a friendly gesture. When Secretary of State William R. Day informed Dupuy de Lôme of the President's proposal, the Spanish Minister consented and the Maine sailed. The Minister found himself having to support policies he personally opposed and to behave cordially to President McKinley. He expressed his private views in a letter dated December 1897 stating that in his opinion the U.S. President-elect was indecisive and irresolute, and that further negotiations with the Cuban insurgents would be futile. The letter somehow reached the Cuban rebels. By February 9, 1898 Secretary Day already had a copy of the letter in his possession. Minister Dupuy de Lôme admitted authorship of the letter and had previously transmitted his resignation to Madrid. Meanwhile the New York Journal, owned by William Randolph Hearst, had printed an English translation of its contents under the banner headline, "The Worst Insult to the United States in Its History." By nightfall, the entire nation knew the contents of the letter and McKinley quickly demanded that the Spanish government apologize. The required response was received from Spain on February 14; two days later the Maine lay at the bottom of Havana harbor.