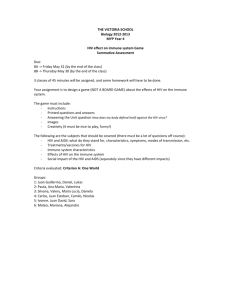

Deliverables for HIV/AIDS Needs Assessment Guidebook

advertisement