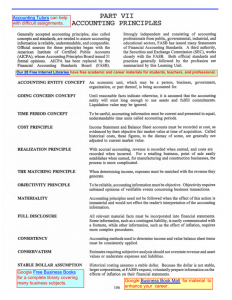

Accounting? - Yale University

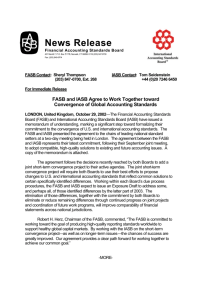

advertisement