21 February, 2011

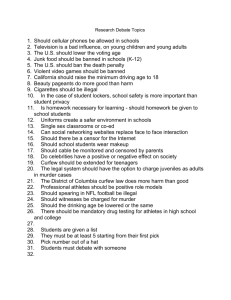

advertisement

TITLE PAGE Why Players Engage in Drug Abuse Substances? A Survey Study Kumar Neeraj1, Paul Maman2, Sandhu J. S3. 1 Lecturer, Dept of Physiotherapy, Saaii College of Medical Science & Technology, Kanpur, U.P., India 2 Lecturer, Faculty of sports Medicine & Physiotherapy, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, Punjab, India 3 Professor, Faculty of Sports Medicine & Physiotherapy, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, Punjab, India Corresponding Author: Maman Paul, B.P.T, M.S.P.T, Lecturer, Faculty of Sports Medicine & Physiotherapy, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, Punjab, India Email: physioner@gmail.com Contact No.: +91-9815459353 ABSTRACT Purpose of this study was to find out the psychological and social support factor which may possibly lead the players towards using drug abuse substances. 303 players were surveyed with a battery of questionnaires consisting questions about performance enhancement attitude, motivation, perfectionism, self confidence, task, ego and social support. 83 players accepted that they have taken banned substances, significant differences were found in their performance enhancement attitude (p<0.001), self confidence (p<0.05) and social support (p<0.001). Result of this study suggested that psychological and social support factors play an important role in players’ propensity to engage in drug abuse substances. This will be the duty of coaches, sports physiotherapist, sports psychologists and sports officials to guide athletes towards a positive approach to encounter the pressure of any competition. Keywords: Drug abuse, psychology, performance enhancement, social support INTRODUCTION Drug abuse is one of the biggest problems in sports. It can also be referred to as substance abuse or doping. Drug abuse involves the repeated and excessive use of chemical substances to achieve a certain effect. It is an unacceptable part of sports and it is illegal because of their adverse effects and performance enhancing actions, moreover, several prohibited drugs may have very high potential for addiction and abuse. These drugs help in increasing muscle mass, strength, and resistance to fatigue, but the utmost advantage of these drugs is their effect on the central nervous system, which makes athletes more aggressive in training and in competition [1]. Doping is a divisive and socially undesirable behaviour and it is an enormously secretive behaviour. Athletes usually do not accept that they are using dope. In the 1998, Tour de France, many of the riders were engage in doping but they refused to accept it. When they got caught in doping test they reacted strangely about its presence in their body and shrugged it off by saying, I wonder how this substance get into my body or I had never taken these drugs [2]. Athletes’ use of illicit substances to excel in performance is a form of cheating behaviour and this could be dangerous for their health and career. The problem of drug use is very common in competitive sports [3]. In spite of the complexity of doping, two major problems arise: health problem and unfair performance enhancement. Both these issues sometimes seen in conflict with the right of autonomy which implies that the athletes can use their body freely [4,5,6], but for the sake of sports, another major issue need to be addressed while dealing with doping is ‘spirit of sport’. The prevalence of doping is higher among sports competitors and increases with age and level of competition [7,8]. There are numerous psychological factors that contribute to a player’s propensity to engage in drug abuse substances, like performance enhancement, perfection, confidence, motivation, task, ego, emotional status and low social support. Unfortunately, much of the research on doping behaviour has so far concentrated on individual differences in attitudes towards drug use and towards drug testing programs. But it is not well understood, what are the underlying psychological factors for the use of performance enhancing substances in sports. There is empirical lack of studies stating the role of psychosocial variables in the use of doping in sports, like, some studies analyzed the performance enhancement attitude with doping belief and sports orientation [9], while few researchers studied the social support determinants of the performance enhancing drugs by gym user [10]. Hence, understanding player’s attitudes and behavioural intentions towards performance enhancement is critical for anti-doping intervention strategies. The current research work was particularly interested in identifying psychological & social variables that might have a link to performance enhancing drug use. Additionally, the present research work will provide useful information for the design of the doping attitudes, which hopefully will serve both a practical and an academic application in the fight against doping in sports. A deeper understanding of decision making processes and player’s disposition towards performance enhancement may point sport managers, officials, policy makers, coaches, sports physiotherapists and even athletes towards a better-targeted approach and may even point the anti-doping effort towards radically different directions. METHODOLOGY A survey study with total of 303 subjects both male and female athletes, aged between 18-35 years, associated with 17 different team or individual sports participated. Athletes of university or higher level were included, whereas athletes taking psychotherapy and handicapped athletes were excluded. Athletes were selected from the various sports centres of Punjab (India). The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, India. Measures: The test consists of the following battery of questionnaires / documents. 1. Consent form: The form allows the participant to state agreement to participate in the study anonymously. The subjects were informed about the confidential nature of the study. The participation was voluntary with no compensation or credit to athletes. 2. Demographic questionnaire: Information on this questionnaire includes personal details, questions relating to sporting experience and doping-specific questions regarding knowledge and use. 3. Performance Enhancement Attitude Scale (PEA) [9]: The PEA scale is a 17- item, six-point Likert-type attitude scale. A high score on this scale will denote positive or permissive attitudes to doping. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale is 0.85. The score can range from 17 to 102. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Perceived Motivational Climate in Sport Questionnaire (PMCSQ-2) [11]: The PMCSQ is a 33-item, 5point Likert-type motivational scale. It contains two subscales (perceived task involving climates and perceived ego involving climates). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale is 0.87. The score can range from 33 to 165. Perfectionism in Sport Scale (PSS) [12]: The PSS is a 24-item, 5-point Likert-type scale to measure attitude and expectations of competitive sport participation. It contains three subscales (coach’s criticism, concern over mistakes, and personal standard). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale is 0.80. The score can range from 24 to 120. Trait Sport Confidence Inventory (TSCI) [13]: The TSCI consists of 13-items in which the participants rate their confidence on a 9-point Likert-type scale. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale is 0.93. The score can range from 13 to 117. Task and Ego Orientation in Sport Questionnaire (TEOSQ) [14]: The TEOSQ comprises 13-items, 5point Likert-type task and ego scale. It contains two subscales (task orientation, and ego orientation). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale is 0.82. The score can range from 13 to 65. Duke-UNC functional social support questionnaire (FSSQ) [15]: It consists of 10-items social support scale to be measured on a 5-points Likert-type scale. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale is 0.81. The score can range from 10 to 50. Protocol: The athletes who volunteered to participate in the study were asked to present on a prescribed date. Only 20 athletes were asked to report at a particular date and time. All participants were assured about the confidential nature of the study and the results will remain anonymous. The participants first filled up the consent form and hand it over to the researcher. After filling the consent form, the participants were asked to complete all questionnaires and give their responses on the response sheet. The participants were then instructed to fold the response sheet, put it in the given envelope & drop it into the prescribed drop box without making any mark on it. Statistical Analysis: Mean, standard deviation, standard error and percentile were used to prepare summary statistics. Karl Pearson Correlation Coefficient (r) and student’s t test were used to determine the association between various questionnaires. The statistical analysis was done on SPSS v 16.00. RESULTS A total of 303 athletes with 277(91%) males and 26(9%) females participated in the study. The average age of the athletes was 24.08 (±4.4) years with 24.46 (±4.3) years of males and 20.12 (±3.1) years of females. Average experience of total athletes was 8.81 (±5.5) yrs. The study comprised of athletes of 17 different sports with following distribution: Archery- 22, Athletics- 48, Badminton- 5, Basket Ball- 41, Boxing- 11, Cricket- 10, Soccer- 40, Gymnastic- 8, Hand Ball-15, Hockey- 23, Judo-13, Swimming- 11, Table Tennis- 1, Taekwondo- 3, Volley Ball-12, Water Polo-21, & Wrestling-19. The level of participation of subjects ranged from university level to international level with, International- 40, National- 181, State- 52, District- 2, & University- 28. Total 83(27%) athletes accepted that they have taken banned substances in which males and females were 74 (26.71%) and 9 (34.62%) respectively. The average age of athletes who have taken banned substances and who have not taken banned substances are 23.51 (±4.7) years and 24.3 (±3.3) respectively, as shown in table 1. The levels of participation of athletes who have taken banned substances are as: International- 15, National- 43, State- 17, District- 1, and University- 7, as shown in figure 1. Total 125 (41%) athletes with 114 (41.2%) males and 11 (42.31%) females accepted that they had received information about banned substances in their sport with 178(59%) did not receive information; distribution is shown in figure 2. Total 118(39%) athletes with 102 (36.82%) male and 16 (61.54%) female accepted that they personally know athletes who are taking banned substances whilst 185(61%) do not know any athlete taking banned substances; its distribution is shown in figure 3. The mean scores of each questionnaire in different categories are given in table 2. Descriptive statistics were calculated in the athletes who have taken banned substances. Descriptive statistics on measurement level variables are provided in table 3. All the measures viz. Performance Enhancement Attitude (PEA), Perceived Task Involving Climate (PTIC), Perceived Ego Involving Climate (PEIC), Coach’s Criticism (CC), Concern over Mistakes (CM), Personal Standard (PS), Task Orientation (TO), Ego Orientation (EO), Trait Sport Confidence Inventory (TSCI) and Functional social Support (FSSQ) were negatively skewed. Student’s ‘t’ test were applied in the score of questionnaires between one group of athletes who have taken banned substances and athletes who have not taken banned substances, the statistically significant differences were found in performance enhancement attitude scale (p<0.001), trait sport confidence inventory scale (p<0.05), and functional social support questionnaire (p<0.001), as shown in table 4. Pearson correlation were applied between PEA Scale and various psychological variables viz. Perceived Task Involving Climate (PTIC), Perceived Ego Involving Climate (PEIC), Coach’s Criticism (CC), Concern over Mistakes (CM), Personal Standard (PS), Task Orientation (TO), Ego Orientation (EO), Trait Sport Confidence Inventory (TSCI) and Functional Social Support (FSSQ) in the group of athletes who have taken banned substances, as shown in table 5. DISCUSSION The aim of the present study was to explore the role of psychological and social support factors which could influence the use of drug abuse substances in sports. Statistically significant differences were seen in PEA-Scale (p<0.001), TSCI (p<0.05) and D-UNC FSSQ (p<0.001) questionnaires between the athletes who have taken banned substances and the athletes who have not taken banned substances. Athletes who accepted that they have taken banned substances had much higher score (mean) on PEA-Scale (69.08) as compared to the athletes who have not taken banned substances (49.43), which demonstrates that they really wanted to enhance their performance, no matter how. This finding is consistent with previous research which suggests that athletes’ win orientation have an effect on doping attitude [9]. It could also be emphasised here that economic status might have inkling towards the winning attitude in athletes as stated by economic theory of doping which mainly assume that athletes act according to economic rationality. Most of the athletes are likely to see doping as their best option and the only feasible strategy to ensure winning [16]. The athletes who indulged in drug abuse substances were less confident (87.11) in their sporting ability than the athletes who did not indulge in such abuse of banned substances (92.17). These findings indicate a direct influence of self confidence over athletes’ attitude to use doping, which is parallel to the findings of Radovanovic et al. (1998) & Donovan et al. (2002) [17,18]. Further, it is also imperative to mention here that in a study conducted by Skarberg et al. (2007) [19], it was found that the anabolic androgenic steroid users were having deprived relationship with their parents and half of them had gone through physical or mental abuse, moreover their childhood was also disturbed and they were socially dissatisfied. The results of the present study also exhibit a similar trend with athletes with low social support (27.64) inclined towards drug abuse than the athletes with high social support (34.64). Another important factor which has emerged from the findings of the present study in curbing the drug menace in sports is the dissemination of information among the athletes about the harmful effects of drug abuse. The results of the present study also suggests that only 125 (41%) athletes received information about banned substances in their sport, whereas out of 83 athletes from the total of 303 who accepted to have taken banned substances, only 28 (33.73%) athletes received information about these substances and rest 55 (66.27%) athletes received no information indicating lack of knowledge about banned substances which probably lead athletes toward engaging in these substances. Education about banned substances in sports is of utmost important as stated by Hardy et al. (1997) [20] that in the Australian Football League doping is not a problem, most likely because an education program is being run by the football authority, similarly Ozdemir et al (2005) [6] also emphasized on education program of doping in sports. In addition, another study by Dvorak et al. (2006) [21] stated that FIFA’s anti-doping strategy relies on education and prevention. In the present survey, it was found that 118 (39%) athletes accepted that they personally know athletes who are taking banned substances. In total of 83 athletes who have taken banned substances, 54 (65.06%) personally know athletes who were taking banned substances; it suggests influence of peer pressure in athletes attitude towards engaging in these substances, these results of present study are supported by the findings of Backhouse et al. (2007) [22], who stated that the appropriate reason for using performance enhancement drugs were own personal interest, personally knowing of athletes who are using and non-conformity of peer group, and by study of Wieffernik et al. (2008) [10], who stated that the psychosocial factors which are more susceptible for the use of performance enhancement drugs are individual norms, to get better performance and noticeable use of others. The results of the present study reveals statistically significant correlation of PEA Scale with perceived ego involving climate (0.46), and coach’s criticism (0.48). These findings suggest that an athlete who perceives high ego involving climate may be at risk for doping. Also, it seems that the criticism made by coach on athletes’ performance creates a negative influence on their perception and could lead them towards doping. Athletes believe that the coach creates an ego involving atmosphere in their team and this ego climate which is created by coach has a significant role in athletes’ behaviour [23]. The results of present study also show significant correlations of PEA Scale with concern over mistakes (0.72) and personal standards (0.43). The behaviour of athletes to show concern over their mistakes and to gauge high personal standards also play a decisive role in drug abuse as shown by the findings of the present study, which is in agreement with Sleasman (2009) [24] who stated that for improving perfection one can move towards the shortcut through artificial stimulants and muscle building hormones. The study by Petroczi et al. (2008) [16] also suggested that the anticipation of perfection for progress and improvement or aspiration to win has an influence on the athletes’ behaviour. Results of the present study show significant correlation of PEA Scale with task orientation (0.24) and ego orientation (0.43). A high task and ego orientation in sports also has a significant role in attitude toward doping by athletes, as suggested by Petroczi et al. (2007) [9] who stated that task and ego orientation had a rational association with doping behaviour. A small negative (but non significant) correlation between PEA Scale and FSSQ (0.008) was seen in the results of present study which indicates athletes’ willingness to enhance performance having low social support with the help of drug abuse substances. The result of the present study also showed that even the university level players (25%) engaged in drug abuse substances, indicating prevalence of doping at this level also; which is a matter of grave concern. The beginner level competition should be fair and players should know the importance of fair play. These results of the present study are consistent with the finding of previous studies, who found that the drug abuse substances are being used by high school athletes in France [7, 25]. In another study, Tahtamouni et al. (2008) [26] found that more than half of the collegiate students of Jordan are using AAS, and they gave emphasis to educate and warn adolescents and mentors about the side effects of AAS abuse. Therefore, the anti-doping strategies are required to prevent the use of these substances by players rather than disqualifying them from competition. A proper assessment of player is necessary, including, medical history, social history and psychological history. An education program for players is essential, as Chan et al. (2005) [27] investigated the opinion, understanding and practice of doping in the local sporting community of Hong Kong and found that the local athletes have no clear picture about dope substances. To prevent local athletes from using these substances, a tailored made education program about doping control is necessary, whereas, Ama et al. (2003) [28] investigated the use and awareness of lawful and unlawful substances by amateur footballers in Cameroon and concluded that prevention of doping through awareness is much essential and the study on prevalence of doping among footballers is urgently needed. In another study, Kayser et al. (2007) [29] reviewed the recent development of increasingly severe anti-doping control measures and found them based on questionable ethical grounds and suggested that the main aim of the current anti-doping strategy is to prevent doping in elite sports by the means of all-out repression, and making it a public discourse. They also suggested that doping prevention is an unachievable task in sports; therefore, a more realistic approach should aim at control and safe use of these drugs which may be practicable choice to deal with doping. The current antidoping policy has received much criticism for its elite focus, sanction-based approach and associated costs [30], apart from these current anti-doping strategies, a need exist to find the deep rooted causes of doping and the results of the present study will help to focus and analyse the basic causes of doping. As such, unless we do not know the basic causes of attitudes towards doping it is very hard to obtain a dope free environment. CONCLUSION The present study reveals that several psychological and social support factors may contribute to the athletes’ propensity to engage in drug abuse substances. These factors include, willingness to enhance performance, high perception of ego involving climate, criticism by coach, much concern of athletes on their own mistakes, athletes’ personal standard, lack of self confidence, low social support, as well as high task and ego orientations. Many athletes through self reported measures revealed that they can improve their performance by engaging in drug abuse in relatively short span of time instead of adapting to advanced techniques. General psychology of the athletes is that in their sports only performance matters, no matter how they achieve it. Some athletes are of view that the banned substances should be legalized in the competition. Inadequate knowledge of dope substances and their adverse effect could also contribute to the use of these substances by athletes. Since less than 50% of athletes accepted that they received information about banned substances in their sport, hence sports officials are required to distribute information booklet to each and every player informing them about the banned substances, because adequate knowledge about these drugs and their adverse effects might help them to avoid using these substances. Psychological factors are very important in player’s decision towards using banned substances, so proper counselling of athletes by sports psychologist is much required. During counselling, social support factors should also be considered. There is no short cut for performance enhancement, but if athletes take this course of doping they may end up with jeopardizing their health. So to save athletes from ruining their health and future of sports by using these substances they should be encouraged to learn new skills and techniques to enhance performance. This will be the duty of coaches, sports physiotherapist, sports psychologists and sports officials to guide athletes towards a positive approach to encounter the pressure of any competition. Emphasis should be given on sports participation and coaches should praise athletes for their effort whether they win or lose, never criticize them for their mistake but try to motivate them to learn from their mistakes. Acknowledgement: We would like to thank all our participants to support us in completing this study. REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. Calatayud, V. A., Alcaide, G. G., Zurian, J. C., Benavent, R. A. (2007). Consumption of anabolic steroids in sport, physical activity and as a drug of abuse: an analysis of the scientific literature and areas of research. Br J Sports Med, 42, 103-109. Peters, C., Schulz, T., & Michna, H. (2002). Biomedical side effects of doping. Project of the European union. Verlag sport and Buch Straub- Koln. Moran A., Guerin, S., Kirby, K., & Maclntyre, T. (2008). The development and validation of a doping attitudes and behaviours scale. Report to WADA & Irish sports council. Mieth, D., & Sorsa, M. (1999). Ethical aspects arising from doping in sports. Opinion of the European group on ethics in science and new technologies to the European commission, 14. Kindlundh, A.M.S., Hagekull, B., Isacson, D.G.L., & Nyberg, F. (2001). Adolescent use of anabolicandrogenic steroids and relations to self-reports of social, personality and health aspects. Euro j of public health. 11:3, 322-328. Ozdemir, L., Nur, N., Bagcivan, I., Bulut, O., Sumer, H., & Tezeren, G. (2005). Doping and performance enhancing drug use in athletes living in Sivas, Mid-Anatolia: A brief report. J of sports sciences & medicine. 4, 248-252. Laure, P., Binsinger, C. (2007). Doping prevalence among preadolescent athletes: a 4-year follow up. Br J Sports Med, 41, 660-663. Ehrnborg, C., & Rosen, T. (2009). The psychology behind doping in sport. Growth hormone and IGF Research. 19:4, 285-287 Petroczi A. (2007). Attitudes and doping: a structural equation analysis of the relationship between athletes’ attitudes, sport orientation and doping behaviour. Biomed central, substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 2:34. Wiefferink, C. H., Detmar, S. B., Caumans, B., Vogels, T., & Paulussen, T. G. W. (2008). Social psychological determinants of the use of performance-enhancing drugs by gym users. Healtheducation research, 28:1, 70-80. Newton, M., Duda, J. L., & Yin, Z. (2000). Examination of the psychometric properties of the perceived motivational climate in sport questionnaire-2 in a sample of female athletes. J of Sports Sciences, 18, 275-290. Anshel, M. H., & Eom, H. J. (2003). Exploring the dimensions of perfectionism in sports. Int J of Sports Psychology, 34, 255-271. Vealey, R. S. (1986). Conceptualization of sport-confidence and competitive orientation: Preliminary investigation and instrument development. J of Sports Psycho, 10, 471- 478. Duda, J. L., & Nicholls, J. G. (1992). Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and sport. J of Edu Psycho, 84, 290-299. Broadhead, W. E., Gehlback, S. H., DeGruy, F. V., & Kaplan, B. H. (1988). The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire Measurement of Social Support in family medicine Patients. Medical care, 26:7, 709-723. Petroczi, A., Aidman, E. V., & Nepusz, T. (2008). Capturing doping attitudes by self report declarations and implicit assessment: A methodology study. Biomed central, substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 3:9. Radovanovic, D., Jovanovic, D., & Rankovic, G. (1998). Doping in nonprofessional sport. Facta Universitatis, Physical education, 1:5, 55-60. Donovan, R.J., Egger, G., Kapernick, V., & Mendoza, J. (2002). A conceptual framework for achieving performance enhancing drug compliance in sport. Sports Medicine. 32:4, 269-284. Skarberg, K., & Engstorm, I. (2007). Troubled social background of male anabolic androgenic steroid abusers in treatment. Biomed central, substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 2:20. Hardy, K. J., McNeil, J. J., & Capes, A. G. (1997). Drug doping in senior Australian Rules football: a survey for frequency. Br J Sports Med, 31, 126-128. Dvorak, J., Graf-Baumann, T., D’Hooghe, M., Kirkendall, D., Taennler, H., & Saugy, M. (2006). FIFA’s approach to doping in football. Br J Sports Med, 40(Suppl I):i3–i12. Backhouse S, McKenna J, Robinson S, Atkin A. Attitudes, Behaviours, Knowledge and Education – Drugs in Sport: Past, Present and Future 2007 http://www.wada-ama.org. 23. Olympiou, A., Jowett, S., & Duda, J. L. (2008). The psychological interface between the coach-created motivational climate and the coach-athlete relationship in team sports. The sport psychologist, 22, 423438. 24. Sleasman, M. J. (2009). Beyond perfectionism. Available at The center for Bioethics and human dignity web site http://www.cbhd.org/content/beyond-perfectionism-0 25. Peretti-Watel, P., Guagliardo, V., Verger, P., Mignon, P., Pruvost, J., & Obadia, Y. (2004): Attitudes toward doping and recreational use among French elite student athletes. Soc Sport J, 21:1-17. 26. Tahtamouni, L. H., Mustafa, N. H., Alfaouri, A. A., Hassan, I. M., Abdalla, M. Y., & Yasin, S. R. (2008). Prevalence and risk factors for anabolic-androgenic steroid abuse among Jordanian collegiate students and athletes. Eur J Public Health., 18:6, 661-5. 27. Chan, K. M., Ping, C., Yuan, Y., & Wong, Y. Y. (2005). A survey on drug usage among Hong Kong elite athletes- opinion, understanding and practice. Hong Kong sports development board. 28. Ama, P. F. M., Betnga, B., Ama, V. J. M., & Kamga, J. P. (2003). Football and doping: study of African amateur footballers. Br J Sports Med, 37, 307–310. 29. Kayser, B., Mouron, A., & Miah, A. (2007). Current anti-doping policy: a critical appraisal. Biomed central, substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, BMC Med Ethics. 8:2. 30. Petroczi, A., & Aidman, E. V. (2008). Psychological drivers in doping: The life-cycle model of performance enhancement. Biomed central, substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 3:7. Tables Category No. of Athletes Mean Age SD Mean Experience Male Female 277 26 24.46 20.12 4.3 3.1 9.24 32.65 5.5 3.9 Athletes who have taken Banned Substances Athletes who have Not taken Banned Substances Male who have taken Banned substances Female who have taken Banned substances Male who have Not taken Banned Substances Female who have Not taken Banned Substances 83 23.51 3.3 8.56 4.6 220 24.3 4.7 8.9 5.8 74 23.75 3.1 8.91 4.4 09 21.44 4.2 5.77 5.3 203 24.71 4.7 9.36 5.8 17 19.41 2.1 3.41 2.9 Table 1: Showing the no. of athletes with mean age and experience in different categories SD Category Male Female Male who have taken Banned substances Female who have taken Banned substances Male who have Not taken Banned Substances Female who have Not taken Banned Substances Athletes who received information about Banned Substances Athletes who did not receive Information about Banned Substances Participants personally know Athletes taking Banned Substances Participants personally do not know any Athlete taking Banned Substances PEA PMCSQ PSS 55.18 (±16.2) 50.81 (±15.9) 69.65 (±17.6) 64.44 (±8.5) 49.92 (±11.9) 43.58 (±14.3) 132.81 (±25.5) 140.23 (±13.1) 136.39 (±18.5) 138.44 (±17.3) 131.51 (±15.3) 141.17 (±10.7) 91.16 (±11.8) 92.31 (±10.3) 93.05 (±13.5) 92.11 (±12.6) 90.47 (±11.1) 92.41 (±9.2) 51.76 (±17.4) 128.73 (±32.1) 56.95 (±14.9) TSCI TEOSQ FSSQ 91.03 (±13.8) 88.19 (±28.2) 89.25 (±15.2) 69.44 (±36.9) 91.67 (±13.3) 98.12 (±15.9) 51.06 (±7.3) 51.04 (±8.1) 52.87 (±7.7) 46.66 (±10.6) 50.41 (±6.9) 53.35 (±5.4) 32.73 (±8.6) 32.65 (±6.9) 27.03 (±9.2) 32.66 (±6.7) 34.81 (±7.4) 32.65 (±7.3) 87.48 (±10.5) 89.32 (±17.1) 50.78 (±7.5) 33.67 (±8.4) 136.76 (±17.1) 93.92 (±12.2) 91.82 (±14.5) 51.26 (±6.9) 32.05 (±7.7) 58.26 (±17.7) 136.92 (±32.9) 93.41 (±10.7) 90.98 (±17.3) 51.85 (±7.4) 29.42 (±8.5) 52.61 (±14.7) 131.24 (±17) 89.89 (±12.1) 90.66 (±14.4) 50.56 (±7.2) 34.83 (±7.7) Table 2: Scores (Mean±SD) of each questionnaire in different categories Variables Min. Max. Mean Performance 34 92 69.08 Enhancement Attitude Scale Perceived Task 44 85 72.49 Involved Climate Perceived Ego 39 82 64.12 Involved Climate Coach’s Criticism 14 30 23.08 Concern over 15 35 27.02 Mistakes Personal Standards 28 55 42.83 Task Orientation 14 35 28.92 Ego Orientation 12 36 23.53 Trait Sport 36 115 87.11 Confidence Inventory Functional Social 9 47 27.64 Support Questionnaire SE SD Variance Skewness Kurtosis 1.86 16.92 286.15 -.454 -1.146 1.17 10.68 114.20 -.770 -.379 1.15 10.49 110.21 -.219 -.989 .36 .55 3.31 5.04 10.93 25.41 -.310 -.346 -.291 -1.035 .74 6.78 .48 4.43 .51 4.65 2.13 19.42 46.02 19.66 21.62 377.19 -.363 -1.052 -.413 -1.302 -.664 1.075 -.174 1.187 .99 82.38 -.153 -.747 Table 3: Measurement level descriptive statistics 9.07 Athletes who have taken Banned Substances Athletes who have not taken Banned Substances (Mean±SD) (Mean±SD) 69.08±16.9 49.43±12.2 9.68*** 136.61±18.3 132.25±15.2 1.935NS PSS 92.95±13.3 90.62±10.9 1.422NS TSCI 87.11±19.4 92.17±13.6 2.184* 52.2±8.2 50.64±6.9 1.549NS Questionnaires PEA-Scale PMCSQ TEOSQ 27.64±9.1 34.64±7.4 FSSQ ***Significant p<0.001, *Significant p<0.05, NS-Non Significant t-Value 6.289*** Table 4: Differences in the questionnaires between athletes who have taken banned substances and athletes who have not taken banned substances PEA Scale r2 Perceived Task Involving Climate 0.07 0.53% Perceived Ego Involving Climate 0.46** 21.71% Coach’s Criticism 0.48** 23.14% Concern over Mistakes 0.72** 51.98% Personal Standard 0.43** 18.41% Task Orientation 0.24* 5.63% Ego orientation 0.43** 18.32% 0.16 2.56% -0.008 0.006% Scale Trait Sport Confidence Inventory Functional Social Support Questionnaire ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed) * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed) Table 5: Correlation between PEA scores & other psychological variables Figures Figure 1: Distribution of level of participation of athletes who have taken banned substances Figure 2: Distribution of athletes on the basis of receiving information about banned substances Figure 3: Distribution on the basis of personally knowing any athlete who is taking banned substances