DRTA Reflection

advertisement

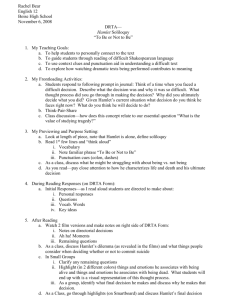

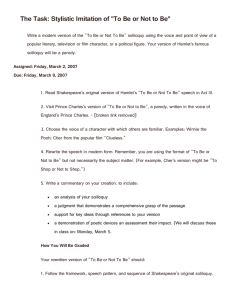

Rachel Bear December 5, 2008 Reflection— DRTA for Hamlet Soliloquies This is my first time teaching 12th grade English and I was quite surprised with the response I got when I mentioned to other student teachers that I was going to do Hamlet with my “regular” 12th grade English class. The general response I got was that Hamlet is “too hard” for them and that I should consider teaching an “easier” Shakespearean text that is shorter. I chose to ignore the responses and teach it anyway. I really think it is one of the most engaging storylines and there are also so many allusions to Hamlet in other works of literature and pop culture that I really feel it is worth the challenge. Furthermore, I figured if I can work through Romeo and Juliet with freshman, I can work through Hamlet with seniors. Of course, we read almost the entire text together in class, stopping frequently to check for understanding and to complete written responses to track the action of the play, but I wanted to design a reading activity that would have them dig in to Shakespeare on their own and work through some of the language. This desire had two purposes 1. Because they can “do” Shakespeare and I wanted to show them that and 2. As a scaffold to prepare them to work with the language on the two culminating projects—an argument essay addressing who is at fault for the tragedy in the play using evidence from the text and a fever chart tracking a specific element for a character. The first DRTA I did was for Hamlet’s “To or Not to Be” speech and it is the one for which I turned in the detailed description of the activity. Essentially, they heard the speech performed four times and were asked to respond in different ways each time. The first reading was done by the student in the class who plays Hamlet and was read in the context of the scene. I then read the soliloquy to them slowly and they were asked to respond with their initial reactions on the left hand column of the page—I modeled the first few lines on the smartboard. We then watched two different film versions of the soliloquy and they were asked to make note of directorial decisions that illuminated some aspect of the soliloquy and write down “ah ha!” moments. Their final task was to pair up and highlight the different elements of Hamlet’s thought process—in one color, highlight events and emotions he associates with life and events and emotions he associates with death. Their final task was to identify his final conclusion and his reason why. I felt like the activity went quite well. Ultimately, students were able to correctly label his thought process and his ultimate conclusion (see student samples). Many of them didn’t write as much as I would expect for their responses to the film versions of the soliloquy. In retrospect, I could have dealt with this by playing each film clip twice so they could just watch the first time and make notes the second time. I also think I could have done a better job of modeling my initial reactions. I meant to explain punctuation cues that help with understanding which events and emotions are associated with either life or death, but I forgot to do that. The second DRTA looked closely at another Hamlet soliloquy—the key moment when Hamlet sees Claudius praying and is torn about whether or not he should kill him. This time I went through a similar process (although I didn’t do a formal written description), but added discussion questions for after reading that dealt with tracking his thought process and two literary terms (hubris and dramatic irony). They first did initial responses and then were placed in groups of four to work through line by line and paraphrase the entire passage. Then they did the discussion questions in small groups before we discussed them as a class. With this activity I was pleased with the initial responses—they seemed more willing to ask questions and take risks—and they had great conversations in their small groups as they tried to make meaning in order to paraphrase. Also, I hadn’t, at this point, introduced dramatic irony, but they picked it up right away and I think discovering it in context was much more powerful than a vocabulary list or notes. The last two questions required them to move beyond comprehension and to start making conclusions about Hamlet’s character and I was quite pleased with their ability to draw some supportable conclusions about him. In the future I can definitely see using this procedure with other difficult reading tasks. I think that, ultimately, this experience helped move them toward being capable of working with the language to locate and integrate evidence from the play for use in the two culminating projects. The fever charts ended up being quite nice, and in their essays (which they are finishing this week), they have been able to find, cite and accurately use key passages from the play. Next time I teach Hamlet I will start earlier in the unit, pick out and use more passages (perhaps all of the essential soliloquies?) and do more modeling in the beginning.