Transaction Costs, Markets, and the Changing Patterns of Local

advertisement

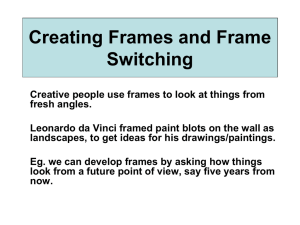

Transaction Costs and the Changing Patterns of Local Service Delivery Trevor Brown School of Public Policy and Management The Ohio State University Matt Potoski Department of Political Science Iowa State University David Van Slyke Maxwell School Syracuse University Paper for Presentation at the 2005 meetings of the Association of Public Policy Analysis and Management, Washington, DC Introduction Public managers can choose from several approaches as they decide how to structure the delivery of goods and services to citizens (see e.g. Salamon, 2002). The three most common service delivery modes are internal service delivery in which the government produces the entire service, contracts with other governments, private firms, or nonprofit organizations, or joint service delivery arrangements, in which the government delivers part of a service and contracts for the rest (Warner and Hedbon, 2001). Traditionally governments’ decision to “make or buy” has been framed statically; public managers select one delivery mode over alternatives and then remain committed to that delivery approach. Of course, in practice service delivery choices can be more fluid: internal service delivery can later change to contract and contracts can later be internalized (Hefetz and Warner, 2004; Lamothe, Lamothe, and Feiock 2004). Changing service delivery modes can be quite costly both in terms of production costs – the financial costs of fixed assets, labor and capital – and transaction costs – the management costs of “…planning, adapting, and monitoring task completion…” (Williamson, 1981, 552553). Varying production and transaction costs make switching from some modes of service delivery easier than others, depending in part on how the service was initially delivered. For example, the costs of switching from internal service delivery to joint contracting with another government may be lower than joint contracting with a private firm because the governments may share common missions and organizational structures. In this paper, we examine the changing pattern of local service delivery by focusing on how governments’ previous service delivery choices structure future choices. We analyze panel data from the 1992 and 1997 International City/County Manager Association’s Alternative Service Delivery surveys along with data from the US Census and other sources. Our results 1 suggest that the previous service delivery mode affects the costs of switching to other services in important ways. Internal service production is quite stable: governments that internally produce a service in 1992 are highly likely to continue internal service provision in 1997. Contracted service delivery is more fluid: governments that contract for service delivery in 1992 are more likely to switch to another mode in 1997. Finally, joint service delivery in 1992 lowers the costs of internalizing service delivery and engaging the market through contracting in 1997. Taken together governments that have already internalized the upfront costs of switching modes of service provision are more likely to approach service delivery choices dynamically. This paper is divided into five sections beyond this introduction. In the first section we lay out our theoretical arguments about the costs of changing service production mode. In the second section we describe the data and methods we use to study these costs. In the third and fourth sections we report the results of our analysis and discuss the findings, before concluding the paper in the fifth section by outlining directions for future research. The Transaction Costs of Switching Modes of Service Delivery Managing service delivery is a complex and dynamic process. Rather than a formulaic progression from one service delivery decision to the next, public managers frequently return to choices they have already made. Notable among these iterative decisions is the question of which mode of service delivery to employ, whether to “make” through internal service delivery, or to “buy” through external contracts. An array of factors influence how public managers choose to deliver services, including political pressures, fiscal constraints, bureaucratic routines, growth demands, and features of services to be delivered (Benton and Menzel, 1992; Brown and Potoski, 2003; Carver, 1989; Ferris, 1986; Ferris and Graddy, 1986, 1991; Hirsch, 1991, 1995; 2 Stein, 1990). Changing circumstances lead governments to reevaluate, and possibly change their initial service delivery decision. With alternatives to direct service delivery becoming more broadly accepted, public managers are increasingly assessing the opportunities to enter and exit service markets (Lamothe, Lamothe, and Feiock, 2004; Hefetz and Warner, 2004). Changing service delivery is costly because of the difficulty of reconstructing current service delivery practices to ensure services continue to be delivered to recipients with as little disruption as possible.1 There are two primary sources of switching costs – changes to production systems and changes to management systems. In terms of production processes, moving from one mode of service delivery to another typically requires defining, designing, and coordinating new tasks necessary to deliver the service. In terms of management processes, switching typically requires establishing new performance criteria, constructing monitoring and evaluation systems, and hiring and integrating new employees or negotiating with existing employees to change their job responsibilities. Both types of costs can arise in addition to any financial costs (i.e. the fixed costs of assets, labor, and capital) associated with changing service production. When these transaction costs of switching are high, public managers are less likely to change the mode of service provision. The current mode of service delivery plays a primary role in determining the level of transaction costs associated with switching. The transaction costs of altering production and management systems vary across different service delivery modes. Some moves are less costly than others because of the nature of how the service is already being produced. The remainder of this section examines the likelihood of changing mode of service delivery for the three primary modes: direct; contract; and joint. Sometimes these costs are referred to as “coordination” costs (Milgrom and Roberts 1992; Besanko, Dranove, and Shanley 1996). 1 3 Direct Service Delivery Switching from direct service delivery to external delivery is likely to be the most difficult because internal production and management systems may be ill suited and challenging to develop for external delivery. When making such a change, switching costs include: downsizing public employees and perhaps negotiating with unions; crafting requests for proposals, establishing systems and protocols for reviewing proposals and selecting vendors; crafting contracts, including developing incentives and formalizing performance measures; negotiating with vendors; integrating new work processes into existing systems, and implementing oversight systems. All of these activities must be undertaken before the previous system can be taken off-line and the new mode of service delivery initiated. Faced with these upfront transaction costs, many direct service provision governments recoil at switching. When direct service provision governments consider service delivery changes, they are likely to find joint contracting the most attractive option because some portion of service delivery is contracted and some is performed internally. There are obviously still endogenous fixed costs associated with joint contracting, such as coordination and adaptation costs, but they are typically lower than complete contracting because internal service production allows more flexibility and leeway in the service production transition. Contract Service Delivery Under contracted service delivery, changing markets, underperforming vendors, and other shifting circumstances may compel managers to seek changes to their service delivery approach (Kettl, 1993; Sclar, 2000). The easiest move is to switch the contract to another type of vendor. Since the government has already outsourced the service, the transaction and production 4 costs of switching are likely to be low. Production systems will only require minor changes since the basic production tasks remain the same; governments that contract have already internalized the costs of altering the production and delivery processes. Furthermore, changes to management systems are likely to be minimal as well; governments can use the same request for proposal, contract, and contract selection processes, perhaps with some slight modifications. However, the costs of switching among vendor types is also likely to vary across circumstances. Some service markets are dominated by one type of organization, leaving little opportunity to switch to another type of vendor if the government is unsatisfied with the current arrangement. For example, social and human service markets are dominated by other governments and nonprofits, while infrastructure service markets are the province of private firms and other governments. A more costly move is to switch to direct service delivery. As is the case in moving from direct to contract service delivery, governments face the transaction costs of changing and adapting production and management systems described earlier. In addition, unless contracting governments have retained some semblance of internal production capacity, the costs of internalization may be prohibitive. Joint service delivery may be an attractive option therefore in terms of production and transaction costs if the contracting government can take partial measures to internalize a portion of the service without incurring the full costs of reintegration. Joint Service Delivery Governments are most likely to switch service delivery modes under joint service delivery. In these cases, governments have positioned themselves to move to either complete contracting or complete internal production. By carrying out some portion of service delivery, 5 these governments typically have established and maintained some of the service production and management systems necessary for direct service delivery. As a result, they do not face the same up front fixed costs of internalization that contracting governments do. At the same time, since they are managing some form of contract service delivery (e.g. crafting contracts and developing performance measures), the transaction costs of transitioning completely to contracted service provision are not nearly as high as if the starting point were from direct service delivery. As a result, joint service production is likely to be the least stable service delivery approach, with governments moving either to internal production or complete contracting. Data and Methods To test our arguments about the impact of transaction costs on changing service delivery, we primarily rely on data from the ICMA’s 1992 and 1997 “Profile of Local Government Service Delivery Choices” surveys, with additional data from the 1997 U.S. Census of Government, a survey conducted by the authors,. The ICMA survey asked a stratified random sample of municipal and county governments a battery of questions about which of sixty-four local services they provided and their service delivery modes. As a result, the ICMA survey is possibly the strongest large sample study of governments’ service production practices. The response rate for each of the two surveys is just over 30 percent: 1,504 municipal and county governments governments participated in the 1992 survey and 1,586 participated in the 1997 survey. The surveys are generally representative of municipalities and counties along basic criteria such as population, geographic location, and metropolitan status. As expected, the samples are over-representative of council-manager governments: between 60 and 70 percent of 6 the respondents in the two samples use this form of government.2 Because we are interested in switching decisions over time, we pair respondents from the two samples. This reduces our working sample to 625 municipal and county governments. We use multinomial logit to evaluate our hypotheses. Multinomial logit provides the analytical mechanism for examining the effect of a constellation of independent variables on the likelihood of respondents choosing each dependent variable category relative to each of the other categories (Long, 1997). The dependent variable is governments’ service production choice for each service they deliver and the independent variables are governments’ previous service production choice for the relevant service and several control measures.3 All estimations are completed using the mlogit command in Stata v. 6. Dependent Variable Respondents to the ICMA survey were asked which of 64 services their government provides and which of a variety of modes are used to deliver each service. Our analyses focus on five service delivery modes – internal delivery, joint contracting, complete contracts with other governments, complete contracts with private firms, and complete contracts with nonprofits.4 The dependent variable is the service delivery mode chosen by each government for each service 2 The 1992 sample under-represents municipal and county governments with populations over one million that are located outside central or suburban metropolitan areas, and municipal and county governments in the New England, Mid-Atlantic, and Southern States. The 1992 sample over-represents municipal and county governments in the Mountain and Pacific Coast states. The 1997 sample is not biased in terms of population or metropolitan status, but again, under-represents municipal and county governments in the Mid-Atlantic and Southern states while overrepresenting those in Mountain or Pacific Coast states. 3 We tested for the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) assumption using Hausman’s diagnostic test (Hausman and McFadden 1984). Results indicated that the assumption is not violated and the choice options are independent. 4 This strategy raises a potential endogeneity problem. That is, some factors that influence governments’ service production choices may also influence their choices about whether or not to provide the service in the first place. Failing to control for such effects risks biased coefficients in our analyses. However, we think such biases are minimal because we believe that governments’ choices of production mechanisms have very little impact on their choices about what services to offer, even at the margins. Governments, or more precisely the elected politicians running them, offer services because their citizens want them. 7 it provides in 1997 so that the responses of one government could be incorporated 64 times in our sample, although not every city provides every service. Service delivery choices are unlikely to be independent within cities, although we can assume independence across cities. That is, a city that chooses to contract for one service may be more likely to contract for other services. However, treating these choices as independent risks artificially deflating the standard errors. To address this issue, we follow White’s approach for robust standard errors, clustered by government (Greene 1997). This adjustment essentially weights each observation (service delivery choice) by the number of services a city provides Independent Variables Our primary independent variable of focus is the previous mode of service delivery for each service. Consequently, we include five independent variables to measure the service delivery mode chosen by each government for each service it provided in 1992. The variable direct 1992 is a dummy variable coded 1 if the city or county directly provided the service in 1992, else zero. The variable joint 1992 is a dummy variable coded 1 if the city or county provided the service in part with public employees in 1992, else zero. The variables other government 1992, private firm 1992, and nonprofit 1992, are each coded 1 if the city or county provided the service through a complete contract with the type of organization identified in the label, else zero. The analyses also include a slate of control variables replicated from a previous crosssectional analysis with the 1997 ICMA data (Brown and Potoski, 2003). The previous analysis demonstrated that service specific transaction costs played an important role in determining mode of service delivery decisions when controlling for other competing explanations and 8 factors. The advance of this current analysis is to build off of a robust empirical model by incorporating a temporal dimension. This allows us to assess the “stickiness” of service delivery choices while controlling for factors previous research has identified as important determinants in the “make or buy” decision. To assess the impact of service-specific characteristics that risk contract failure we incorporate measures of asset specificity and ease of measurement. Asset specificity refers to whether specialized investments are required to produce the service. Ease of measurement refers to how easy or difficult it is for the government to measure the outcomes of the service and/or to monitor the activities required to deliver the service. To measure these service characteristics, we surveyed 75 randomly selected city managers and mayors across the country asking them to rate the asset specificity and service measurability of the 64 ICMA listed services.5 The survey instrument provided half-a-page description of the two specific transaction cost risk factors associated with services – asset specificity and ease of measurement. An appendix presents the definitions used on the survey instrument. The instrument then asked respondents to rate each of the 64 services included in the ICMA survey on two scales of one to five, one scale for asset specificity and one for ease of measurement. We then averaged these ratings across respondents to create the service characteristic independent variables asset specificity and ease of measurement. Higher values indicate that the service is more asset specific and therefore more difficult to measure. Because the asset specificity and ease of measurement may vary across different levels of these transaction costs, we also include squared measures of these variables, asset specificity2 and ease of measurement2 (Brown and Potoski 2003). Governments were randomly selected with two sample stratification criteria – population and type of government (council-manager versus mayor-council). Thirty-six usable surveys were returned for a response rate of 48 percent. 5 9 To measure transaction cost risks stemming from market characteristics, we focus on the metropolitan status and the size of the population of the government’s jurisdiction. Metropolitan areas have larger markets of potential vendors that facilitate external production. The analyses therefore include a dummy variable (metropolitan area) scored one if the government is located within an SMSA, else zero. Governments with large populations within metropolitan areas are likely to decrease external production, while governments with large populations outside of metropolitan areas are likely to increase their use of external service delivery. We measure population as the number of residents living within the government’s jurisdiction as reported in the 1990 US Census. To investigate these market competition hypotheses, the analyses include the variables population and population squared along with interaction terms for metropolitan area x population and for metropolitan area x population squared. We employ several approaches to assess the influences of cities’ historical-political development on their service delivery patterns. First, we distinguish cities according to when they achieved metropolitan status under the Census Bureau’s Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA) guidelines (Bogue, 1958). Stein (1990) argues that 1929 marks the end of the industrial period and the beginning of the post-industrial period era. The variable industrial city identifies those cities located in a SMSA prior to 1929 (coded as one, otherwise zero). Because of the rich market of suburban governments around these governments and their weak tax bases, these cities may be more likely to produce services externally through complete or joint contracting than others cities. Second, to assess the affect of annexation limitations, we operationalize the variable annexation limitation. Following Hill’s (1978, 1993) examination of annexation authority dimensions, we combine state level annexation regulations to create an annexation scale, ranging from least to most restrictive. This variable is scaled so that its mean is 10 zero and standard deviation is one. We expect that an increase in annexation limitation increases the likelihood of external service production. Research suggests that council-manager governments are more likely to produce services externally through complete or joint contracting than other forms of government. To control for this argument we include a dummy variable, called council-manager, scored one if the government is a council-manager form of government, else zero. Many contracting scholars (e.g. Ferris 1986; Stein 1990; Hirsch 1991, 1995) point to the seminal importance of post-1978 property tax limitations that began in California and were subsequently employed in some other states. While any overall property tax limitation may create fiscal pressures for municipal governments, the post-1978 state tax limits sought to reduce governments’ role in society and consequently tended to be highly restrictive. These limitations created incentives for governments to be more efficient and creative in service delivery. Governments in states with extensive property tax limitations may therefore be inclined to seek alternatives to internal delivery, particularly those in states with post-1978 property tax limitations. We include two measures to assess the affect of overall tax limitations on service delivery choices. The variable tax limit identifies those respondents located in a state that adopted an overall property tax limitation prior to 1978 (coded as one, else zero). The variable tax limit 1978 identifies respondents located in states that adopted an overall property tax limitation in 1978 or after (coded as one, else zero). While we expect that both groups of respondents are more likely to produce services externally than other respondents, we particularly expect this to be the case for governments included in the tax limit 1978 variable. Similarly, governments with low levels of human and fiscal resources are likely to produce more services externally. Low revenue and human resource capacity create fiscal imperatives to either 11 not deliver services or to find low cost service delivery approaches (Gargan 1981; Honadle 1981). The variable fiscal capacity is the overall general revenue per capita, as reported in the 1997 US Census of Governments.6 We include both municipal and county governments because, as general service units, the services they provide are typically quite extensive and in many instances similar, but because the services responsibilities of the two types sometimes differ, the analyses include a government type dummy variable. The variable county is scored one if the respondent is a county, else zero. Results This section reports the results of the empirical analysis. Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for all variables. Figure 1 and 2 report the percentage of services that are delivered via each mode in 1992 and 1997, respectively. Table 2 reports results of the multinomial logit analyses of the determinants of service delivery choices in 1997. This table compares the likelihood of respondents selecting the base service delivery mode (listed in the table title) relative to each of the service delivery modes listed on the four right-hand columns. Specifically Table 3 reports the likelihood of municipal and county governments selecting direct delivery in 1997 relative to selecting joint delivery, contracts with other governments, contracts with private firms, and contracts with nonprofits. To help with interpretation, we calculated the “predicted effects” of the independent variables of interest in this study – the service delivery modes in 1992 (Long 1997). These results are reported in Figure 3. [INSERT TABLE 1 HERE] 6 We elect not to include a measure of human resource capacity since our measures of staffing are highly positively correlated with fiscal capacity. 12 Before turning to the results that inform the focus of our inquiry, it is important to examine the overall use of different service delivery modes in the ICMA data as reported in Figures 1 and 2. Figure 1 and 2 report the percentages of service delivery practices across the five delivery modes in 1992 and 1997. In both 1992 and 1997, over 60 percent of all services delivered are delivered directly. Joint service delivery is the second most frequently used mode of service delivery, accounting for just over 20 percent of all services delivered in both time periods. Contracting with other governments, private firms, and nonprofits accounts for fewer than 20 percent of all services delivered in each time period. While these figures do not specifically speak to switching between modes, they do suggest that movement across service delivery modes occurs at the margins and there is inertia associated with service delivery choices. [INSERT FIGURES 1 AND 2 HERE] Table 2 reports the results of our multinomial logit analysis of municipalities’ service delivery decisions. Overall, the results support our theory about how the transaction costs of switching influences governments’ service delivery decisions from one time period to another. The multinomial results in Table 2 indicate that service delivery choices in 1992 have the most consistent significant effect on service delivery choices in 1997, and generally speaking they do so in the manner in which we predicted. Service specific transaction costs – notably asset specificity and ease of measurement – display statistically significant impacts on service delivery choices consistent with previous studies (Brown and Potoski, 2003). The other variables included in the analysis demonstrate less consistent impact on service delivery choices in 1997, if they 13 display any impact at all. We discuss the impact of past service delivery choices in more detail below by presenting the predicted effects of 1992 service delivery modes on 1997 service delivery modes in Figure 3. [INSERT TABLE 2 HERE] The Impact of Past Service Delivery Modes on Current Service Delivery Modes Figure 3 reports the likelihood (i.e. the predicted effect) of a municipal or county government selecting each mode of service delivery in 1997 for a given service based on how the service was delivered in 1992, with all other variables in the analysis held constant at their means. For example, the first column in the figure reports the likelihood of a municipal or county government selecting each of the five modes of service delivery in 1997 given that they delivered the service directly in 1992. Here we discuss the likelihood of switching from each of the three primary modes of service delivery. [INSERT FIGURE 3 HERE] Direct Service Delivery As expected, governments are unlikely to switch service delivery modes when they provide services directly; the likelihood of a government providing a service directly in 1997 given that they provided it directly in 1992 is .8, controlling for other factors. This supports our contention that the costs of changing direct production and management systems are high when governments are producing services internally. To the degree that these governments do switch, 14 they are most likely to switch to joint service provision (.15), supporting our claim that the transaction costs of such a change are substantially lower than moving to a complete contract with either another government, a private firm, or a nonprofit. Contracted Service Delivery Figure 3 also shows that governments that contract are much more dynamic in their service delivery decisions. Governments that contract with other governments, private firms or nonprofits in 1992 have a smaller than .5 probability of continuing their service delivery approach in 1997, holding constant the effects of other variables. Governments that contract with nonprofits in 1992 are the least likely to continue with the same vendor type in 1997 (.4). The predicted effects provide only mixed support for our argument that contracting governments are most likely to change vendor types – should they elect to change – because the transaction costs of switching are low. The probability of a government that contracted for service delivery with another government in 1992 and then switching to a private firm or a nonprofit in 1997 is only .05 and .04, respectively. Similarly, the probability of a government that contracted with a private firm in 1992 switching to another government or a nonprofit in 1997 is only .06 and .03, respectively. These patterns may be due to the vendor types selected in 1992 dominating the service markets in question, thus leaving few alternatives among other types of vendors. Governments that contract with nonprofits provide the most support for our contention about the costs of switching among vendor types. The probability of a government that contracted with a nonprofit in 1992 switching to another government or a private firm in 1997 is .15 and .16, respectively. 15 Across all three contract delivery modes, governments are most likely to move to joint service delivery if they are to change their service delivery mode. The probability of switching to joint service delivery ranges from .14 to .23 across the three vendor types, while the likelihood of switching to direct service delivery ranges from .14 to .29. This supports our contention that partial steps are less costly than fully changing service delivery mode to complete contracting. Joint contracting can sometimes serve as an intermediary stage between one mode and the other. Taken together, contracting governments are highly likely to switch with their choice of service delivery mode being the most diverse. Joint Service Delivery Governments that jointly delivered services in 1992 are the most likely to switch to direct service delivery in 1997. In fact, joint service delivery governments are about as likely to switch to direct service delivery (.45) as they are to remain with joint service delivery (.41). This is consistent with our argument that joint service delivery governments retain some degree of production and management capacity necessary for direct service delivery and consequently incur lower transaction costs in returning to direct service delivery. The results also support our contention that joint service delivery governments can easily move in the other direction toward contracted service delivery. However, the relatively lower likelihoods of joint service delivery governments switching to complete contracts with other governments (.06), private firms (.07), or nonprofits (.02) suggests that the transaction costs of completely turning to the market for service delivery are higher than bringing the service back in-house. 16 Conclusion The high transaction costs of altering existing production and management systems and constructing new systems make switching service delivery modes costly. Governments do not often change service delivery modes. However, the production and transaction costs of switching vary across service delivery modes and make some moves more likely than others. In general, the costs of exiting direct service delivery for contract service delivery are high; managers have to dedicate significant time and effort to dismantling existing production and management systems and building new ones. As a result, direct service delivery governments are most likely to stick with their current mode. On the other hand, because they have typically already incurred the transaction costs of switching in the past, contracting governments’ service delivery decisions are more dynamic. Sometimes these governments move back towards internalization from joint or contracted service delivery, while other times they remain in the market by switching vendor type. Finally, governments are most likely to change delivery modes for jointly produced services, perhaps because the switching costs are lower. Service delivery mode is dynamic, but the likelihood of switching modes of delivery is strongly influenced by the prior service delivery mode. The argument we present here, while powerful, is straightforward. The changing patterns of service delivery are certainly influenced by other factors beyond the prior service delivery mode. Building from our argument about the production and transaction costs of switching, we hypothesize that there are other related factors that influence the costs of switching. In particular, there may be spillover effects for governments that engage market alternatives to direct service delivery across a range of services. As governments contract for more services – or engage in more joint service delivery – relative to direct service delivery, they may achieve 17 economies of scale in altering production and management systems, at least for similar types of services (e.g. infrastructure services, social services). For example, governments that contract for high numbers of social services may find that they face lower transaction costs of switching additional social services from direct to contract service delivery because they have experience in constructing similar kinds of production and management systems. In future research we intend to test this and related arguments about other factors that influence the transaction and production costs of switching modes of service delivery. References Benton, J. Edwin, and Menzel, Donald C. 1992 “Contracting and franchising: County services in Florida.” Urban Affairs Quarterly, 27 (3): 436-456. Besanko, David, David Dranove, and Mark Shanley. 1996. Economics of Strategy. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Bogue, D. 1953 Population growth in standard metropolitan areas: 1900-1950. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Brown, T., & Potoski, M. 2003. Transaction costs and institutional explanations for government service production decisions. Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory, 13(4), 441-468. Carver, Robert H. 1989 “Examining the premises of contracting out.” Public Productivity & Management Review, 8 (1): 27-40. Ferris, James. 1986 “The decision to contract out: An empirical analysis.” Urban Affairs Quarterly, 22: 289-311. Ferris, J., and Graddy, E. 1986 “Contracting out: For what? With whom?” Public Administration Review, 46: 332-344. Ferris, J., and Graddy, E. 1991 “Production costs, transaction costs, and local government contractor choice.” Economic Inquiry, 24: 541-554. Gargan, James. 1981 “Consideration of local government capacity.” Public Administration of Review, 41 (6): 649-658. Greene, W. 1997 Econometric analysis, 3rd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Hausman, J., and McFadden, D. 1984 "Specification tests for the multinomial logit model." Econometrica, 52:1219-1240. Hefetz, Amir, and Warner, Mildred. 2004. “Privatization and Its Reverse: Explaining the Dynamics of the Government Contracting Process,” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 14(2): 171-190. Hill, M. 1978. State laws governing local government structure and administration, 1st ed. Athens: University of Georgia Institute of Government. Hill, M. 1993. State laws governing local government structure and administration, 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations. 18 Hirsch, Werner Z. 1991 Privatizing government services: An economic analysis of contracting out by local governments. Los Angeles: Institute of Industrial Relations. Hirsch, Werner Z. 1995 “Contracting out by urban governments: A review.” Urban Affairs Review, 30 (3): 458-472. Honadle, Beth Walter. 1981 “A capacity-building framework: A search for concept and purpose.” Public Administration Review, 41 (5): 575-580. Kettl, Donald. 1993 Sharing power: Public governance and private markets. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. Lamothe, Meeyoung, Lamothe, Scott, and Feiock, Rick. 2004. Vertical Integration and Municipal Service Provision. Paper presented at the 2004 meetings of the Association of Policy Analysis and Management. Long, J.Scott. 1997 Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Milgrom, Paul, and John Roberts. 1992. Economics, organizations, and management. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. Salamon, Lester M. 2002 The Tools of Government: A Guide to the New Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sclar, Elliot. 2000 You Don’t Always Get What You Pay For: The Economics of Privatization. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. Stein, Robert. 1990 Urban Alternatives: Public and Private Markets in the Provision of Local Services. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. Warner, Mildred., and Hedbon, Robert. 2001 “Local government restructuring: Privatization and its alternatives.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 20 (2): 315-336. Williamson, Oliver. 1981 “The economics of organization.” American Journal of Sociology, 87: 548-577. 19 Table 1: Descriptive Statistics Variable Mean Std. Dev. Min Max 1a. Direct 1997 .62 -- 0 1 1b. Joint 1997 .21 -- 0 1 1c. Other Government 1997 .08 -- 0 1 1d. Private Firm 1997 .07 -- 0 1 1e. Non-Profit 1997 .02 -- 0 1 1a. Direct 1992 .63 .48 0 1 1b. Joint 1992 .20 .40 0 1 1c. Other Government 1992 .09 .29 0 1 1d. Private Firm1992 .06 .24 0 1 1e. Non-Profit 1992 .02 .13 0 1 2. Asset Specificity 3.07 .63 1.76 4.26 3. Asset Specificity Squared 9.84 3.96 3.11 18.16 4. Ease of Measurement 2.67 .63 1.53 4.3 5. Ease of Measurement Squared 7.53 3.69 2.34 18.53 6. Metropolitan Area .075 .44 0 1 2115 2122101 4473225 4.5x1012 Dependent Variables Independent Variables 7. Population 67252.03 149982.9 10 11 8. Population Squared 2.7x10 9. Metro*Population 59303.06 151899.9 0 2122101 10 11 0 4.5x1012 10. Metro*Population Squared 2.66x10 2.3x10 2.3x10 11. Council-Manager .68 .47 0 1 12. Industrial City .03 .167 0 1 13. Annexation Limitation -.02 .78 -1.78 .84 14. Tax Limit .12 .33 0 1 15. Tax Limit 1978 .16 .36 0 1 16. Fiscal Capacity (1 = $1000/capita) 1.21 .74 .01 4.74 17. Fiscal Capacity Squared 2.02 2.70 .00 22.46 18. County .15 .35 0 1 20 Table 2: Multinomial Logit Analysis of Determinants of Service Delivery Mode in 1997 (Direct 1997 as Base of Comparison) Direct 1997 versus…. Independent Variable Direct 1992 Joint 1992 Other Government 1992 Private Firm1992 Non-Profit 1992 Asset Specificity Asset Specificity Squared Ease of Measurement Ease of Measurement Squared Metropolitan Area Population Population Squared Metropolitan Area * Population Metropolitan Area * Population Squared Council-Manager Industrial City Annexation Limitation Tax Limit Tax Limit 1978 Fiscal Capacity (1 = $1000/capita)7 Fiscal Capacity Squared County Joint 1997 Other Governments 1997 Private Firm 1997 Nonprofits 1997 -5.63*** (.64) -4.06*** (.64) -4.47*** (.64) -3.79*** (.64) -3.92*** (.67) .24 (.28) -.05 (.04) 2.66*** (.31) -.49*** (.05) .34* (.20) 4.22x10-6 (7.48x10-6) -1.25x10-11 (4.95x10-11) -3.13x10-6 (7.41x10-6) 1.18x10-11 (4.94x10-11) -.00 (.12) -.29 (.29) -.13 (.07) -.13 (.15) .15 (.14) .05 (.19) -.01 (.05) -.16 (.19) -1.12 (.89) .25 (.92) 2.90*** (.91) 1.04 (.88) 2.37*** (.93) -.37 (.46) .14** (.07) -1.29*** (.46) .17*** (.08) .02 (.25) 2.06x10-6 (9.42x10-6) 1.4x10-11 (4.25x10-11) -3.6x10-6 (9.24x10-6) -1.54x10-11 (4.24x10-11) .12 (.19) -.41 (.53) -.10 (.09) .12 (.20) .21 (.19) -.35 (.29) .04 (.08) -.18 (.32) .66 (.89) 2.17*** (.90) 2.43*** (.89) 5.04*** (.89) 4.21*** (.55) .73 (.55) -.08 (.09) -3.47*** (.40) .57*** (.07) .00 (.23) -9.08x10-6 (8.55x10-6) 5.32x10-11 (4.03x10-11) 7.57x10-6 (8.45x10-6) -5.26x10-11 (4.02x10-11) -.14 (.16) -.03 (.38) .00 (.09) .03 (.20) .36* (.20) -.36 (.25) .07 (.07) -.65* (.27) -3.79** (1.6) -1.75 (1.57) -.34 (1.58) -.34 (1.58) 2.59* (1.58) -3.01*** (.75) .46*** (.12) 2.44*** (.82) -.39*** (.14) -.57* (.32) -1.5x10-5 (1.06x10-5) 8.01x10-11* (4.47x10-11) 1.44x10-5 (1.04x10-5) -7.97x10-11* (4.47x10-11) .45* (.26) .30 (.27) -.07 (.13) .05 (.28) -.15 (.28) -.39 (.33) .09 (.08) .57* (.36) Log likelihood -16042.71 Pseudo R2 .46 N (observations) 18510 N (clusters, governments) 625 Notes: standard errors in parentheses; *** p < .01, ** p < .05, *p< .10, two tailed tests. 7 We use the log of fiscal capacity in all of the multinomial logit analyses. 21 Figure 1: Percentage of Services Delivered by Mode 1992 Nonprofit 2% Private Firm 6% Other Government 9% Joint 20% Direct 63% Figure 2: Percentage of Services Delivered by Mode 1997 Nonprofit 2% Private Firm 7% Other Government 8% Joint 21% Direct 62% 1 Figure 3: Service Delivery Mode Likelihood '97 by Mode '92 1 0.8 Nonprofit 0.00 Nonprofit 0.02 Nonprofit 0.04 Private Firm 0.03 Private Firm 0.07 Private Firm 0.05 Other Govt 0.03 Other Govt 0.06 Joint 0.15 Nonprofit 0.03 Nonprofit 0.40 Other Govt 0.49 Joint 0.41 Private Firm 0.49 0.6 Other Govt 0.06 0.4 Joint 0.16 Joint 0.23 Private Firm 0.16 Other Govt 0.15 Joint 0.14 0.2 Direct 0.80 Direct 0.45 Direct 0.26 Direct 0.19 Direct 0.14 0 Direct 1992 Joint 1992 Other Government 1992 2 Private Firm 1992 Nonprofit 1992