Replace This Text With The Title Of Your Learning Experience

advertisement

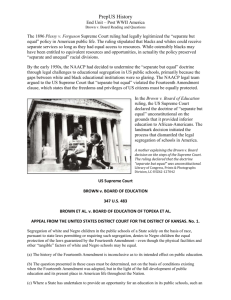

Brown v. Board of Education – The Struggle for Equality Matthew Mills Mahomet Seymour Junior High School Spring 2013 Farm Security Administration – Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress) Collins, Marjory, 1912-1985, photographer 1942 Mar. The Brown v. Board of education ruling on May 17, 1954, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th Amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" precedent set by the Supreme Court nearly 60 years earlier and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement during the decade of the 1950s. This learning activity explores the events that led up to the Brown v. Board of Education ruling and the impact it had on the civil rights movement. Students will analyze several primary sources to get an overall understanding of the importance of the case in relation to African Americans achieving civil rights. Overview/ Materials/LOC Resources/Standards/ Procedures/Evaluation/Rubric/Handouts/Extension Overview Objectives Recommended time frame Grade level Curriculum fit Back to Navigation Bar Students will: Integrate multiple resources to understand the significance of the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas case. Explain the effect the landmark case had on the Civil Rights Movement. List observations from photos. Create a timeline of events from the Civil Rights Movement. Analyze the Landmark Supreme Court Case Plessey v. Ferguson 1896. Analyze the Landmark Supreme Court Case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. 5 class periods Upper Middle School (8th Grade) Social Studies Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Materials Copies of segregated African American schools from resource table: Marjory Collins. Reading lesson in African American elementary school in Washington, D.C. African American public school in Louisa, Virginia, 1935 Veazy, Greene County, Georgia. The oneteacher Negro school in Veazy, south of Greensboro. Copies of Plessy v. Ferguson case brief. Copies of Brown v. Board of Education case brief. Copies of marches/demonstrations during Civil Rights Movement from resource table: People marching with signs to protest segregation in education at the college and secondary levels. African American students arriving at Little Rock Central High School. Rosa Parks being fingerprinted. Ministers protesting outside Woolworths. Selma March. Copies of Photo Analysis Worksheet. Copies of Civil Rights Timeline. Illinois Learning Standards/Common Core Back to Navigation Bar ILS-Social Studies GOAL 16: Understand events, trends, individuals and movements shaping the history of Illinois, the United States and other nations. 16.A Apply the skills of historical analysis and interpretation. 16.A.3b Make inferences about historical events and eras using historical maps and other historical sources. 16.A.3c Identify the differences between historical fact and interpretation. 16.B Understand the development of significant political events. 16.B.3c (US) Describe the way the Constitution has changed over time as a result of amendments and Supreme Court decisions. Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Procedures Back to Navigation Bar Day One: The students will read and complete the case brief for the Plessy v. Ferguson case. The students will look at primary source photographs of segregated facilities in the South. Discuss their findings for each picture and talk about Jim Crow laws in southern states after the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling. Day Two: The students will look at primary source photographs of African American schools before Brown v. Board of Education. The students will complete the document analysis worksheet for each picture. Discuss their findings for each picture and ask how they thought white schools were different during this time. Day Three: The students will read and complete the case brief for Brown v. Board of Education case. Discuss their findings and talk about the significance of the Supreme Court ruling for challenging other forms of segregation. Day Four: The students will look at primary source photographs of Civil Rights groups protesting other forms of segregation after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. The students will complete the Analyzing Primary Source Worksheet for each. Discuss findings from the photographs and the focus of the Civil Rights Movement after Brown v. Board of Education. Day Five: Students will complete the Civil Rights Timeline Assignment using the website provided. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/civilrights/crexhibit.html The students will select 10 events for the timeline and identify the significance of the event. The students will be evaluated using the rubric below. Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Evaluation Back to Navigation Bar Extension Photograph Analysis Worksheets will be collected and given a participation grade. The Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board of Education case briefs will be graded for content base on student responses to the questions. The Civil Rights Timeline will be graded for content and grammar. Extension activity will be graded for students who complete the assignment. The students will also have an assessment at the end of the Civil Rights Movement Unit. Back to Navigation Bar Students will be given the option of researching a Civil Rights figure for an extension activity. This will be used if a student finishes the timeline early or needs an enrichment activity. Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Primary Resources from the Library of Congress Back to Navigation Bar Image Description Man drinking at “colored” water fountain in the street car terminal, Oklahoma City. Citation Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, Reproduction number: LCDIG-fsa-8a26761 DLC (digital file from original neg.) URL http://www.loc.gov/exhibi ts/civilrights/images/cr000 5s.jpg Marjory Collins. Reading lesson in African American elementary school in Washington, D.C. Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress) Collins, Marjory, 19121985, photographer 1942 Mar. http://www.loc.gov/pictur es/item/owi2001003177/P P/ African American public school in Louisa, Virginia, 1935 Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USAVisual Materials from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Records 1935 Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, Reproduction number: LCUSF34-046248-D DLC (b&w film neg.) http://www.loc.gov/pictur es/item/2005693014/ J.H. Lawson, Houston, Texas, 1947. Visual Materials from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Records, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division http://www.loc.gov/pi ctures/item/96515743/ Veazy, Greene County, Georgia. The one-teacher Negro school in Veazy, south of Greensboro. People marching with signs to protest segregation in education at the college and secondary levels http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/fsaall :@filreq(@field(NUMBE R+@band(fsa+8a26761)) +@field(COLLID+fsa)) http://memory.loc.gov/ser vice/pnp/fsa/8c07000/8c0 7400/8c07419r.jpg http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/fsaall :@field(NUMBER+@ban d(fsa+8c07419)) Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University African American students arriving at Central High School, Little Rock, Arkansas, in U.S. Army car Woman fingerprinted. Mrs. Rosa Parks, Negro seamstress, whose refusal to move to the back of a bus touched off the bus boycott in Montgomery, Ala. Washington, D.C. 20540 Reproduction number: LCUSZ62-116817 (b&w film copy neg.) Keating, Bern. 1947 U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsc00182 (digital file from original) http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/p p.print Associated Press photo. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection. 1956. Exhibited: With an Even Hand: Brown v. Board of Education at Fifty Years, Durham Western Heritage Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, 2005-2006. Protest by ministers Associated Press photo. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection April 14, 1960. Exhibited: Voices of Civil Rights, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., 2005 Participants marching in Peter Pettus.1965. the civil rights march Exhibited: Voices of Civil from Selma to Rights, Library of Montgomery, Alabama in Congress, Washington, 1965. D.C., 2005. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ppmsca08102 (digital file from original http://www.loc.gov/exhibi ts/civilrights/images/cr001 3s.jpg http://www.loc.gov/pi ctures/item/98502283/ http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ cph.3c09643 http://www.loc.gov/pi ctures/item/94500293/ http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ ppmsca.08096 http://www.loc.gov/pi ctures/item/95514178/ http://www.loc.gov/exhibi ts/civilrights/images/cr003 0s.jpg http://www.loc.gov/pi ctures/item/20036753 45/ Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University Rubric Back to Navigation Bar Timeline : Civil Rights Timeline Teacher Name: Mr. Mills Student Name: ________________________________________ CATEGORY Dates 4 An accurate, complete date has been included for each event. 3 An accurate, complete date has been included for almost every event. 2 An accurate date has been included for almost every event. 1 Dates are inaccurate and/or missing for several events. Content/Facts Facts were accurate for all events reported on the timeline. Facts were accurate for almost all events reported on the timeline. Facts were accurate for most (~75%) of the events reported on the timeline. Facts were often inaccurate for events reported on the timeline. Readability The overall appearance of the timeline is pleasing and easy to read. The overall appearance of the timeline is somewhat pleasing and easy to read. The timeline is relatively readable. The timeline is difficult to read. Spelling and Capitalization Spelling and capitalization were checked by another student and are correct throughout. Spelling and capitalization were checked by another student and were mostly correct . Spelling and capitalization were mostly correct, but were not checked by another student. There were many spelling and capitalization errors. Total Score = ____________X2=______________/32 Points Teaching with Primary Sources Illinois State University HANDOUTS Back to Navigation Bar Name_____________________Class__________ Brown v. Board of Education (1954) Background Summary and Questions In Topeka, Kansas in the 1950s, schools were segregated by race. Each day, Linda Brown and her sister, Terry Lynn, had to walk through a dangerous railroad switchyard to get to the bus stop for the ride to their all-black elementary school. There was a school closer to the Brown's house, but it was only for white students Topeka was not the only town to experience segregation. Segregation in schools and other public places was common throughout the South and elsewhere. This segregation based on race was legal because of a landmark Supreme Court case called Plessy v. Ferguson, which was decided in 1896. In that case, the Court said that as long as segregated facilities were equal in quality segregation did not violate the Constitution. However, the Brown's disagreed. Linda Brown and her family believed that the segregated school system did violate the Constitution. In particular, they believed that the system violated the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteeing that people will be treated equally under the law. No State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. —Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) helped the Browns. Thurgood Marshall was the attorney who argued the case for the Browns. He would later become a Supreme Court justice. The case was first heard in a federal district court, the lowest court in the federal system. The federal district court decided that segregation in public education was harmful to black children. However, the court said that the all-black schools were equal to the all-white schools because the buildings, transportation, curricula, and educational qualifications of the teachers were similar; therefore the segregation was legal. The Browns, however, believed that even if the facilities were similar, segregated schools could never be equal to one another. They appealed their case to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Court combined the Brown's case with other cases from South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware. The ruling in the Brown v. Board of Education case came in 1954. (Answer questions on back) Questions to Consider: 1. What does it mean to have segregated schools? 2. What right does the Fourteenth Amendment give citizens? 3. How did the case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) affect segregation? 4. Do you think the separate schools in Topeka were equal? How were they different? 5. It is important for this case to determine what "equal" means. What do you think equality means to the Browns? What do you think equality means to the Board of Education of Topeka? Name_______________________Class________ Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) Background Summary and Questions In 1890, Louisiana passed a statute called the "Separate Car Act", which stated "that all railway companies carrying passengers in their coaches in this state, shall provide equal but separate accommodations for the white, and colored races, by providing two or more passenger coaches for each passenger train, or by dividing the passenger coaches by a partition so as to secure separate accommodations. . . . " The penalty for sitting in the wrong compartment was a fine of $25 or 20 days in jail. The Plessy case was carefully orchestrated by both the Citizens' Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Act, a group of blacks who raised $3000 to challenge the Act, and the East Louisiana Railroad Company, which sought to terminate the Act largely for monetary reasons. They chose a 30-year-old shoemaker named Homer Plessy, a citizen of the United States who was one-eighth black and a resident of the state of Louisiana. On June 7, 1892, Plessy purchased a firstclass passage from New Orleans to Covington, Louisiana and sat in the railroad car designated for whites only. The railroad officials, following through on the arrangement, arrested Plessy and charged him with violating the Separate Car Act. Well known advocate for black rights Albion Tourgee, a white lawyer, agreed to argue the case without compensation. In the criminal district court for the parish of Orleans, Plessy argued that the Separate Car Act violated the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution. Thirteenth Amendment Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Fourteenth Amendment Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. John Howard Ferguson was the judge presiding over Plessy's criminal case in the district court. He had previously declared the Separate Car Act "unconstitutional on trains that traveled through several states." However, in Plessy's case he decided that the state could choose to regulate railroad companies that operated solely within the state of Louisiana. Therefore, Ferguson found Plessy guilty and declared the Separate Car Act constitutional. Plessy appealed the case to the Louisiana State Supreme Court, which affirmed the decision that the Louisiana law as constitutional. Plessy petitioned for a writ of error from the Supreme Court of the United States. Judge John Howard Ferguson was named in the case brought before the United States Supreme Court (Plessy v. Ferguson) because he had been named in the petition to the Louisiana Supreme Court and not because he was a party to the initial lawsuit. Questions to Consider: 1. What law did Homer Plessy violate? How did Plessy violate this law? 2. What rights do the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution provide? 3. If you were Plessy's lawyer, how would you justify your claim that the "Separate Car Act" violates the Thirteenth and Fourteenth amendments? 4. Is it possible for two races to remain separated while striving for equality? Are separation and equality compatible? Why or why not? 5. Can you think of an example or situation where separation does not mean inequality? Name______________________Class_________ Civil Rights Timeline (20 Points) You will construct a timeline of major events from the struggle for African American Civil Rights. Use the webpage below to choose at least ten events for your timeline. You will put the date of the event and a brief description on the timeline. Next, for each event explain the importance to the overall Civil Rights Movement on the second page. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/civilrights/cr-exhibit.html 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Extra Events: