Basis-for-Medical

advertisement

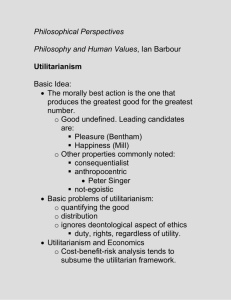

5th Medical Year Jurisprudence Ethics Uncovering the Conflicting Approaches There are various ways of addressing the moral issues which arise in the context of health care, and each of these approaches to the issues is based upon a particular theoretical stance, which, broadly speaking, stresses a particular set of values and beliefs. In the literature on ethics these moral theories are usually identified as deontological, consequentialist, or virtue-based. Because they stress different values as morally fundamental these moral theories are at least potentially in conflict with one another. Deontological Moral Theories A deontological approach to ethical questions in general, and to the more specific moral questions inherent in health care practice, makes the question of what we can rightfully do to other people of central concern. Hence the emphasis on notions such as 'rights', 'duties' and 'obligation'. Perhaps the principal proponent of a deontological approach to moral questions was the eighteenth century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who expanded on a much older tradition of thought on the moral importance of human beings. Of importance and interest to us here is the stress Kant places on the rationality of mankind, as opposed to other species, and the implications for this for the question of how we must treat such beings. His Categorical Imperative says, for instance, that we can never be acting rightly if what we do involves treating another human being merely as a means to our own ends. And wrong actions are irrational actions and vice-versa - because they are contrary to our essential human nature as rational beings. The stress on rationality as the distinguishing feature of human beings - as that which makes them morally important - was part of the older Judaeo-Christian tradition within which Kant was working. But his exposition of this traditional line of thought has lead some thinkers to stress the rational and autonomous nature of human beings above every other moral consideration. The consequence of this has been to expose a difference of opinion or approach existing within deontological moral theory: 1. An emphasis on duty This approach to moral matters reflects the traditional Judaeo-Christian morality of the western world. That is not to say however that it is necessarily religion based, but more that this sort of approach to 5th Medical Year Jurisprudence Ethics ethical problems in the context of medical practice stresses the wrongness of contravening certain rules, which are taken to be morally fundamental. This way of confronting ethical issues, based on some notion of our duties to others, will usually give central place to a cluster of prohibitions on what we may do to other people. For example, the Principle of the Sanctity of Human Life forbids the killing of an innocent human being, in any circumstances. This duty-based approach is also likely to recognise prohibitions on lying and torture, as well as upholding other traditional doctrines such as the view that that there is a morally significant difference between killing a person and allowing them to die (the ActsOmissions Distinction); and that there is a limit to the amount and sort of harm which may be done in order to bring about good (the Doctrine of Double Effect). These views form the major content of a duty-based morality, but this approach will also preclude breaches of professional codes of conduct such as the duty to avoid harming a patient and to respect patient confidentiality. Also of great significance for health care practitioners is the emphasis within this view of moral matters, on the duty to act in the best interests of the patient at all times. Perhaps, this approach to the question of what is morally important may be best captured by pointing out that it makes the moral agent, the person who must act, the centre of moral concern. He/she must do what is morally required by the rules even if, for instance, the breaking of one of these rules would give the patient what he wants and chooses, and even if it would result in a decrease in suffering overall. Thus a duty-based practitioner will not contravene the Principle of the Sanctity of Life by performing euthanasia even when it is the express wish of a fully competent patient or when that patient is suffering greatly. (He or she may, though, and without any fear of contradiction, allow that patient to die earlier rather than later, or reduce the suffering by the use of painkilling drugs even when these have the effect of shortening the patient's life). It would be mistaken to understand this approach to moral issues as one of the inflexible application of rules. Doing the right thing here is not a matter of blindly following rules but is much more difficult and subtle and - more than any other approach- it requires the exercise of good judgement. 2. An emphasis on rights Within a deontological view of ethical questions we can also identify an approach to ethical issues 5th Medical Year Jurisprudence Ethics where the central focus of concern is rational and autonomous persons and the respect that is due to them. A rational and autonomous person is said to possess rights and these must be respected because they enable him/her to determine what happens in their own life - even if what is chosen is detrimental to their own welfare. Thus respecting a person's autonomy is of paramount moral importance (as long as doing so does not infringe someone else's autonomy) and the focus of concern shifts from the moral agent and whether he obeys certain moral rules to the way his actions impinge upon other autonomous individuals. Hence, contrary to the views of a duty-based morality, the rights-based moralist will contravene the Principle of the Sanctity of Life quite happily in a request for euthanasia, as long as the request comes from a rational and autonomous patient. Indeed the rights-based moralist will condemn any refusal to break this Sanctity of Life principle in such circumstances as an important violation of a fundamental right. Typically on this view, moral problems become issues about whether someone has been wronged (have their rights been violated?) rather than issues about whether wrong has been done. Because the respect for the autonomy of a person is of overriding importance it follows that one could wrong a person (by, for instance, violating his right to choose the treatment he wants) even though one benefits him (by, for instance, giving him the best treatment available). Conversely, one might harm him (by providing the least efficacious treatment) without necessarily wronging him. A rights-based moralist would thus regard the concealment of a possible treatment option from a patient, for instance, as an example of wronging a person without harming her. And conversely, he would maintain that a doctor who deliberately submits a patient who is informed and gives a valid consent, to a harmful piece of research, for example, does not thereby wrong her. Contrary to both a duty-based and a consequentialist view of ethical issues, both of which subordinate the value of respect for autonomy to other values, the rightsbased approach to ethical issues insists on the importance of individual choice or autonomy above every other concern. Consequentialist/utilitarian moral theory Utilitarianism is both a theory of the good and a theory of the right. As a theory of the good, utilitarianism is welfarist, holding that the good is whatever yields the greatest utility --'utility' being defined as pleasure, preference-satisfaction, or in reference to an objective list of values. As a theory of the right, utilitarianism is consequentialist, holding that 5th Medical Year Jurisprudence Ethics the right act is that which yields the greatest net utility. Utilitarianism was originally proposed in 18th century England by Jeremy Bentham and others, although it can be traced back to ancient Greek philosophers such as Parmenides. Bentham found pain and pleasure to be the only absolutes in the world: "nature has put man under the governance of two sovereign masters: pleasure and pain." From this he derived the rule of utility: that the good is whatever brings the greatest happiness to the greatest number of people. Later, after realizing that the formulation recognized two different and potentially conflicting maximanda, he dropped the second part and talked simply about "the greatest happiness principle". John Stuart Mill wrote a famous (and short) book called Utilitarianism. Although Mill was a utilitarian, he argued that not all forms of pleasure are of equal value, using his famous saying "It is better to be Socrates dissatisfied, than a fool satisfied." He disagreed with Bentham's hedonic calculus holding that quality is better than quantity. Utilitarians appraise any proposed course of action, not as to whether it is in line with exemplary moral conduct as laid down by a particular moral code, nor as to whether it respects the rights of an individual, but simply as to whether or not the consequences of the action produce as much good for as many people as possible in the circumstances. There are sometimes difficulties; of course, about saying precisely what counts as 'good'. But leaving aside the problems of defining and measuring the good, utilitarians claim they have a rational method of resolving moral conflicts by ranking all possible courses of action in terms of the total amount of 'good', or the least amount of 'harm', each would produce. The right action, morally-speaking, is the one that leads to the most benefit, or the least harm, for the largest number of people. Hence a utilitarian is prepared both to break moral rules and to violate rights if he/she can be certain that the total welfare will be increased by so doing. For a utilitarian, therefore, we cannot do wrong, nor wrong a person, unless we harm or at least fail to benefit him. For instance, a utilitarian faced with a request for euthanasia from a terminally-ill patient in great pain, would take into account the suffering of the individual, the needs of his or her family and the interests of others who may benefit from his death in terms of access to scarce medical resources. He/she would probably conclude that, in these circumstances, complying with the patient's request would increase the total 5th Medical Year Jurisprudence Ethics welfare and is therefore the right thing to do. However, if complying with the request for euthanasia would for some reason not lead to an increase in benefit more generally then the utilitarian would refuse the request for euthanasia even though the individual patient may suffer greatly as a result. Thus, provided there is an overall increase in benefit, even if a person is made to suffer one does no wrong (contrary to duty-based morality) and neither does one wrong the individual concerned (contrary to rights-based morality). In acting to maximise the 'good' utilitarians are prepared deliberately to impose burdens upon one person in order to benefit others. For many -and perhaps in particular for health care workers committed to individual patients - this will be morally unacceptable. (Though in a world of scarce resources and responsibility for financial budgets that view may be changing!). But, to be fair, contemporary utilitarians rarely reject outright the moral importance of following rules or of respecting rights. On the contrary they have often worked assiduously to accommodate these different moral concerns by arguing that, ultimately, following certain rules and respecting rights are most likely to produce the most 'good' for society. On the other hand, it should be noted that the place given by utilitarians to rules and rights is essentially conditional - it depends entirely on their actually being conducive to the greatest good of the greatest number. Other varieties of utilitarianism have also been proposed. The traditional form of utilitarianism is act utilitarianism, which states that the best act is whichever act would yield the most utility. A common alternative form is rule utilitarianism, which states that the best act is the one that would be enjoined by whichever rule would yield the most utility. To illustrate, consider the following scenario: A surgeon has six patients: one needs a liver, one needs a pancreas, one needs a gall bladder, and two need kidneys. The sixth just came in to have his appendix removed. Should the surgeon kill the sixth man and pass his organs around to the others? This would obviously violate the rights of the sixth man, but utilitarianism seems to imply that, given a purely binary choice between (1) killing the man and distributing his organs or (2) not doing so and the other five dying, violating his rights is exactly what we ought to do. 5th Medical Year Jurisprudence Ethics A rule utilitarian, however, would look at the rule, rather than the act, that would be instituted by cutting up the sixth man. The rule in this case would be: "whenever a surgeon could kill one relatively healthy person in order to transplant his organs to more than one other person who needs them, he ought to do so." This rule, if instituted in society, would obviously lead to bad consequences. Relatively healthy people would stop going to the hospital, we'd end up performing many risky transplant operations, etc., etc. So a rule utilitarian would say we should implement the opposite rule: don't harvest healthy people's organs to give them to sick people. If the surgeon killed the sixth man, then he would be doing the wrong thing. Criticism of Utilitarianism Critics of utilitarianism claim that this view suffers from a number of problems, one of which is the difficulty of comparing utility among different people. Many of the early utilitarians hoped that happiness could somehow be measured quantitively and compared between people through felicific calculus, although no one has ever managed to construct one in practice. It has been argued that the happiness of different people is incommensurable, and thus felicific calculus is impossible, not only in practice, but even in principle. Defenders of utilitarianism reply that this problem is faced by anyone who has to choose between two alternative states of affairs where both impose burdens to the people involved. If happiness were incommensurable, the death of a hundred people would be no worse than the death of one. Utilitarianism has also been criticized for leading to a number of conclusions contrary to 'common sense' morality. For example, if forced to choose between saving one's child or saving two children of strangers, most people will choose to save their own child. However, utilitarianism would support saving the other two instead, since two people have more total potential for future happiness than one. John Rawls rejects utilitarianism, both rule and act, on the basis that it makes rights depend on the good consequences of their recognition, and thus he argues that it is incompatible with liberalism. For example, if slavery or torture is beneficial for the population as a whole, it could theoretically be justified by utilitarianism. Utilitarians argue that justification of either slavery or torture would require improbably large benefits to outweigh the direct suffering to the victims and that Rawl's analysis excludes the indirect impact of social acceptance of inhumane policies. (The issue in particular rests on who is included in the evaluation: animal welfare 5th Medical Year Jurisprudence Ethics activists may argue that the suffering of farm animals is immoral on utilitarian grounds if including other species in the overall assessment.) 5th Medical Year Jurisprudence Ethics Virtue Theory: According to the moral theories we have looked at so far, a good person is one who either respects the rights of others or follows certain rules outlining our duties to others, or who always tries to produce the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people. Despite their differences, all of these theories give a central place to reason and not much to the role of feeling in moral decisionmaking. An alternative to this is an approach called virtue theory which has become very influential in ethics literature recently but is, in fact, based on the writings of Aristotle (384-322 BC). For Aristotle, the virtues are those qualities a person has which enable her to achieve well-being i.e. to live a flourishing life, (Notice that this is a much broader conception of our usual narrowly 'moral' notion of virtue) To lack these virtues means that one can never attain the sort of life human beings were created for -'the good life'. So what is this peculiarly human virtue that enables us to lead a flourishing life? Aristotle says it is the exercise of reason. So far, this emphasis on reason may remind us of the other sorts of moral theories and in particular the views of Kant, who insisted that right action was action dictated by reason and set against desire or inclination. But for Aristotle, the role of reason, though crucial, was only a small part of what constituted right action. Many other things in addition to reason are necessary. Some examples he gives are a congenial home life, material possessions, leisure time, a certain amount of money, education, friends, beauty, health and freedom. And among these conditions for human flourishing he places what we call moral virtues such as courage, honesty etc. According to Aristotle, each person must develop the virtues in himself and thereby learn to judge what is appropriate in each circumstance. He says it is easy to formulate rules of right conduct -such as 'Be generous'- but to be generous to the right person at the right time and in the right amount, is difficult and requires a fine moral judgement for which no specifications can be given. This has to be learned through experience and habit. Aristotle's point is that, without the possession of the virtues a person will sometimes do the right thing; but, in general, such people will lack the means of ordering their emotions and desires or of deciding rationally which emotions and desires to cultivate and which to quash. Hence he makes it clear that virtues are not only dispositions to act in certain ways, but also to feel and think in certain ways.