No. 00-1260 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

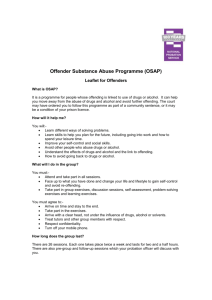

advertisement