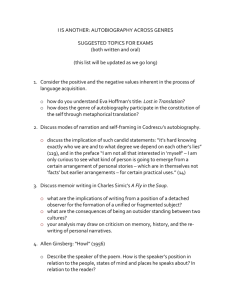

Cens anthol #2

advertisement