click here - stop church child abuse

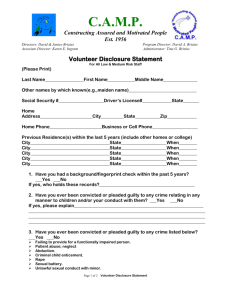

advertisement