Full Report

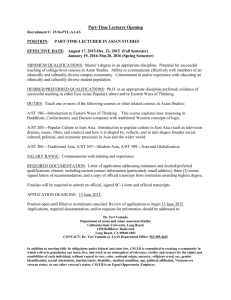

advertisement