ICR_Corruption_and_Competition_Notes

advertisement

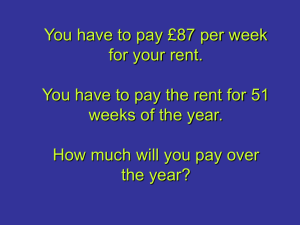

International Commercial Relations Notes on Corruption and Competition* Economic rent = that part of income paid to a factor of production (land, labor, capital, and entrepreneurship) in excess of which is needed to keep it employed in its current use. excess income from labor = earnings that are over and above what is normally paid for a given type of work (unearned income, i.e., “wages” that were paid but not deserved for the work done) Suppose you work for a government agency in charge of approving applications for licenses to operate a business in a certain town or city. You are paid, say, $36,000 a year (or $3,000 a month) by the government. Suppose further that you have “indicated” in the past that you could help speed up the application process “under certain favorable conditions.” This means that you are rent seeking (looking for economic rent). If a license applicant (say, an entrepreneur) gives you, say, $5,000 in secret (under the table) to help speed up his application to get a license, then, if you accept, you have received total earnings of $8,000 for a month. This amount is bigger than what you are normally paid a month to keep you working on this job. The $5,000 is economic rent. It’s the excess income paid to a factor of production (labor in this case) over and above what you normally get paid to keep you working in this job. If the license applicant (the entrepreneur) believes that, with the license, he will make money (from the business he will open as a result of the license) that is more than what he would normally earn from operating just any other businesses (excess profits), then he is also rent seeking. Rent seeking then is an attempt to obtain economic rent (‘good’ or ‘bad’ economic rent) by manipulating the environment (people, groups, institutions, etc.) in a legal (lobbying or contributions to political parties) or illegal means (bribes, illegal political contributions, or private mafias) for personal or company gains. Economic rent is generated by the self-interested decisions and actions of entrepreneurs and companies (or individuals, or institutions in some cases), both by their anti-competitive and their pro-competitive conduct (behavior). Indeed it is precisely the promise of earning a temporary monopoly rent (meaning high or excess profits) that spurs (leads to) innovation, which could be in the form of a new blockbuster product (say, a blockbuster drug like Prozac or Viagra), an improved work process (say, just-in-time inventory or kaizen), a new approach to marketing (viral marketing), or a superior logistics chain (say, supply chain management). Examples of pro-competitive methods: - passing laws that open and liberalize (free) markets, ensuring open competitive and transparent bidding for projects, reducing the length of patent protection, a firm competing fairly and not illegally, a company not getting special or privileged treatment, Examples of anti-competitive methods: - passing regulations that prevent potential competitors from entering a market, granting patent protection, lobbying for laws that discriminate against other competitors, collusion by companies, price-fixing, bribery, unfairly subsidizing some companies and not others, a company getting special or privileged treatment, a business getting unfair subsidy, Essentially, rent seeking is, by itself, not bad as long as it is done through legal and competitive means or methods (creating ‘good’ rent) but it is bad when done by illegal or anti-competitive methods (creating ‘bad’ rent). The rent seeking costs incurred in creating ‘good’ rents are those incurred in the costly and risky process of research and development (R &D), most clearly evident in the case of new product development. The rent seeking costs incurred in creating ‘bad’ rents are those money spent on bribing politicians, government officials, institutions, etc., or illegally lobbying lawmakers and/or politicians to pass laws that limit competition or market entry. But it is also the promise of economic rent that gives the company an incentive or motivation to collude with its competitors or to take action designed to exclude rivals or would-be rivals from its market (prevent market entry). Competition Law and Enforcement The role of competition law is to ensure that these lucrative (excessive) monopoly rentsrents effectively derived from market imperfections (say, when there is a single seller (monopoly) or if there are only few sellers)are created and maintained by pro-competitive conduct (behavior) rather than by anti-competitive conduct. In the language of enforcement, competition law enforcement is intended to ensure that rent is not secured by means of anti-competitive mergers or collusion, and that the rents are not maintained by exclusionary conduct (keeping competitors out), including abuse of the patent process. “abuse of the parent process” = when a patent protection is given to a new product but unduly or unfairly excludes (in a reasonable amount of time) other companies from offering a competing product that could result in lower prices for consumers What is the relationship between economic rent and competition? And why do we need to know about it? The relationship between economic rent and competition: economic rent would be driven down or would decrease when there is competition. Stated differently, low levels of competition correlate well (is related highly) with high levels of corruption (an inverse relationship). There is a cause and effect between competition and corruptionlow levels of competition drives or causes high levels of corruption. Conversely, high levels of corruption undermine competition (cause less competition). The mechanism (or how): Because low levels of competition lead to higher (economic) rents, the potential returns from, and the incentive to engage in, corruption are increased. Thus, if we want less corruption in the economy, we can do this by having more or better competition. Conversely, if we want more competition, then we can do this by trying to reduce corruption. So, part of the job of the Korean Fair Trade Commission (FTC) is catch rent seeking companies that create ‘bad’ rent through illegal ways (say, by collusion, price-fixing, or mergers), hoping that its action would lead to more competition. On the other hand, the Indonesian government may be better off not granting the wishes of Foxconn (like free land) as a condition (or requirement) for building a $1 billion factory in Indonesia because this could lead to ‘bad’ rent in Indonesian society and an uneven (unfair) playing field with Foxconn possibly gaining excess profits as a result. Industrial Policies Industrial policies and support programs are designed with the goal of securing rents. That is to say the provision of governmental support is actually designed to incentivise (provide incentives to) private investment in selected firms or sectors. This support may take on many forms. industrial policy = a strategic effort to grow and develop the competitiveness and capabilities of specific manufacturing sectors of an economy (specific means ‘selective’ in that some firms are selected to receive the programs but others are not; the question is: how is it decided that some companies are worthy of support and others are not? The criterion could be subjective (rather than objective), which is not good.) However, the programs generated by industrial policy (for selected firms or sectors) are generally rooted in the (i) effective creation of monopoly rights, or, at least (ii) some form of protection from competition, or (iii) the granting of a privileged position in the competitive process Examples: - protection from international competition - export incentives - the subsidisation of R&D costs or workforce training costs - the provision of concessionary finance - the extension of an exclusive license to operate in a prescribed area - an exemption from a country’s competition law - the provision of a targeted piece of infrastructure – for example, the construction of a rail link between an inland mine and a port - creation of an industrial or economic free zone Note that many countries in the world have at one time or another pursued industrial policies. In the case of Korea in the 1960s, selected companies in the government-targeted industries received (i) low-interest (often negative-interest) loans, (ii) export subsidies, and (iii) tax credits, but only if they successfully competed in the open international markets. It was an exportoriented industrial policy. Beginning in the mid 1970s, Korea selected and supported heavy equipment manufacturing and petrochemical industries as the next step in its export-oriented industrial policy. Big investments in these industries were undertaken by a few select familycontrolled large conglomerates, known as chaebol, that to this day continue to dominate the Korean economy. Thus the too-big-tofail syndrome was born in Korea. Encouraged by government subsidies and below-market-rate loans, some chaebol made huge investments in heavy industries financed by enormous debt, a very risky move. The Korean government feared that allowing unprofitable chaebols to go bankrupt would trigger a widespread chain reaction and damage the entire economy. So the Korean government bailed them out. Under this policy environment, it made economic sense for a chaebol to choose very risky, large-scale investments even if it did not promise a lot of profits. If the investments turned out to be profitable, the chaebol would reap the benefit from the risky investment. If the investments failed, then the chaebol could rely on a more-or-less certain government bailout. These investments contributed to the growth of the Korean economy in the 1980s and 1990s, but sowed the seeds for the deep economic crisis (set the stage for the downfall) that gripped the Korean economy in 1998 when the Asian foreign exchange crisis in late 1997 exposed the vulnerability of many chaebols. Definition of Corruption A commonly cited definition of corruption as ‘the abuse of public power and public resources for private gain’. Different societies have different perceptions (ideas or beliefs) of corruption due to differences in culture, tradition, customs, or history. Where an action is perceived (or thought of) to be corrupt in one society, it may be normal practice and acceptable in another. It is written, for example, that in Indian societies, with the passage of time, corruption has become a way of doing things, a tradition, a psychological need and, eventually, a necessity so to speak. In Southern Italy, it is also written that it is common to support the interests of the nuclear family (both parents and their dependent children as a social unit) where people expect individuals to care exclusively for their immediate family, take advantage of those outside the family (strangers), and expect everybody else to behave in the same way. Thus, corruption in the form of nepotism and all that derives or comes from this particular corrupt practice is seen as acceptable. nepotism = the practice by those in power or influence of favoring or giving jobs to their immediate family members or relatives What does this mean about hiring policies in Southern Italy? It is also written that in Latin America corruption is not only a social deviation (an unusual social practice), it is a way of life. In Mozambique, it is believed that paternalism and patronage networks play an important role in society. As a result, behaviours which are usually considered conflicts of interest, nepotism, and favoritism are not generally viewed as corrupt. Instead, Mozambicans who achieve ‘important’ positions are commonly expected to use their position to help family members and friends. The terms used to describe corruption and bribery are also culturally and nationally derived, all are invariably euphemistic (mildly labeled). For example, a traffic policeman in North Africa may ask a motorist for a cup of coffee, while in South Africa you would be asked for a ‘cooldrink’, in Kenya for ‘tea for the elders’ and in Turkey for ‘cash for soup’. In Hungary doctors and nurses will refer to the envelope of money received from their patients as a ‘gratuity’ (tip) while in China healthcare workers and government officials expect ‘yidian xinyi’ or ‘little token of gratitude’, while in Russia, the expression ‘you cannot put ‘thank you’ in your pocket’ commonly come before a discussion that ends in the payment of a bribe. In languages and cultures as diverse as English, Farsi, French and Swedish, a popular term for corrupt payments translates into English as ‘money passed under the table.’ _____________________________________ * Based mostly on “Fighting Corruption and Promoting Competition” by David Lewis, OECD, Directorate for Enterprise and Financial Affairs, Session I of Global Forum on Competition, February 17, 2014. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DAF/COMP/GF(2014)1&docLanguage=En