Harmonic Analysis

advertisement

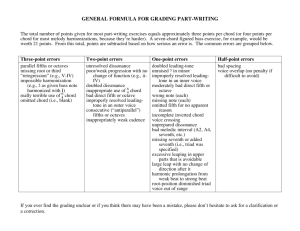

Chapter 5 Harmony “Tonal Colors”: Arpeggiated Structures & Superimpositions In a 1960 article for the Jazz Review, Gunther Schuller observed that Montgomery “demonstrates his marvelous warmth and sense of tonal color,- a tonal color varied and fitted according to the character of the phrase.”1 Later in the text, Schuller also employed words such as “tonal shadings” to describe and explain Montgomery’s music. Schuller’s observations are significant because these so-called “tonal colors” one senses at first hearing are an integral part of Wes’ improvisational syntax, and are responsible for generating the “modern sound” so characteristic of his style. Guitarist George Benson also recognized Montgomery’s innate ability to exploit disparate tone colors over various harmonic backgrounds: “Harmony is the whole thing.... The most modern and hippest guitarist of our time was Wes Montgomery, because of his marvelous use of substitute notes for the harmonic ones.”2 The transcriptions and analyses establish that Montgomery uses an intricate but consistent system of chord superimpositions when manipulating tonal colors. In a 1970 interview with Michael Brooks, guitarist Larry Coryell acknowledged and briefly explained this major aspect of Wes’ style: After studying all those Wes Montgomery solos, I started to get one or two ideas about how to think. For example, if he was playing a blues in C, instead of thinking C as he was starting to do his chorus in the beginning, he would think Bflat major 7, and that’s how he would get his moderness.3 1 Gunther Schuller, “Indiana Renaissance,” Jazz Review, vol.2, no.8, 1959. 2 Robert Yelin, “George Benson,” in Jazz Guitarists: Collected Interviews From Guitar Player Magazine (New York: Music Sales Corporation, 1975), 21. 3 Michael Brooks, “The Eleventh House: Larry Coryell” in Jazz Guitarists: Collected Interviews From Guitar Player Magazine (New York: Music Sales Corporation, 1975), 33. 2 During the bebop era4 musicians had been actively engaged in the harmonic expansion of jazz improvisation. They incorporated and emphasized chord tones beyond the seventh degree of a vertical chord structure in their linear improvisations.5 Guitarist Charlie Christian, Montgomery’s principal influence, was among those who led the change to bop. New sounds and new ideas were discernible in the famous Charlie Christian recordings of 1941-sessions from Monroe’s Uptown House and Minton’s in New York City. There is no doubt that Montgomery assimilated these new sounds and ideas, however, Christian’s style did not exhibit the level of harmonic sophistication and “tonal coloring” typical of Montgomery’s improvisations. Arpeggiated Structures: Analytical Procedure Analyses of Wes Montgomery’s solo transcriptions reveal the prevailing use of various types of triadic, four-note, five-note, and six-note chordal structures outlined in the improvised line. It is evident from the compiled data that Montgomery had a strong inclination towards the use of arpeggiated structures. It is in the distinctively personal way he employed these diverse structures and their superimpositions, that made his harmonic language so unique. Because part of this section specifically analyses arpeggiated structures and their harmonic effect on the improvised line, we had to formulate special analytical and classificatory procedures that would be applicable and relevant to our study, and would effectively demonstrate Montgomery’s usage of these structures in the context of a solo improvisation. A preliminary analysis confirmed that Montgomery employed varying types of arpeggios (minor, major, minor seventh, major seventh, etc.) with various 4 Steven Strunk, “Harmony” in The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, ed. by Barry Kernfeld, 2 vols. (New York: MacMillan Press Limited, 1988), 1:494. Strunk provides an historical perspective of the development of chordal extensions as employed in jazz, “The 1940’s brought the decline of the big-bands and the evolution of bop, which is mainly associated with small groups. Charlie Parker and his colleagues worked out numerous harmonic innovations, which to a great degree defined the new style: they placed melodic emphasis on the upper pitches of extended chords,.......” 5 Steve Rehbein, “An Examination of Milt Jackson’s Improvisational Style,” in 1991 IAJE Research Papers (Manhattan, Kansas: IAJE Publications, 1991), 58. 3 superimpositions when improvising. Therefore, during the preliminary analyses and collection of data (table 1) each arpeggiated structure was analyzed and classified according to genre (minor, major, major seventh-ascending or descending) or more specifically, chord type. We included the abbreviated title of the composition from which the improvisation was transcribed, and the measure where the particular structure could be found. In addition, the rest of the analysis indicated the chord or harmonic background on which the structure is improvised, the intervallic relation of the structure to its harmonic background, and the scale degrees and extensions generated when the structure is superimposed over a harmonic background. This method of classifying similar-type chordal structures enabled us to compile large amounts of information pertaining to Montgomery’s use of chordal superimposition and facilitated the process of deciphering and interpreting the data. Table 1: Preliminary Analysis (example) Minor Triad Descending (root position-5/3) Year Structure Tune Measure # Harmonic Superim- Degrees Back- position Extensions ground 1959 Gm triad “Missile Blues” 62 C7 min. ch. 5-7-9 Perfect 5th up 4 1960 Am triad “Four Six” on 33 Gm7 min. ch. 9-11-13 maj2 up Model built in Thirds According to Steven Strunk, “the most ‘natural’ arrangement of chord tones and tensions is in ascending thirds. This arrangement provides each tension with a chord tone a seventh below, bringing its dissonance aurally to fore.”6 The model of this arrangement illustrated in example 1 lists chord tones and tensions in ascending thirds when read clockwise.7 Throughout the various analyses we observe that Montgomery’s employment of chordal structures in the improvised line is based on this widely-used ascending-thirds model. Ex.1 Model built in thirds Ex.2 Model built in fourths 6 Steven Strunk, “Bebop Melodic Lines: Tonal Characteristics,” Annual Review of Jazz Studies, Vol. 3 (1983), 102. 7 Ibid., 103. 5 Voicings stressing fourths have also been popular in jazz, especially modal jazz, because they also have the dissonant seventh interval (the seventh is the sum of adjacent fourths).8 However, the model built in fourths illustrated in example 2, eliminates the “sweet sound” characterized by the model built in thirds. In his improvisations Montgomery does not superimpose fourths melodically to produce chord tones and extensions. The model built in fourths does not reflect Montgomery’s syntax.9 Major Structures Table 2 Major Ascending Chord Structures Structure Type Occurrences Major triad (5/3) 61% 5/3 four-note 10% 6/3 triad 12% 6/3 four-note 1% 6/4 triad 8% 6/4 four-note 8% 8 Ibid., 104. 9 Ibid., 108. Strunk adds that arpeggiations within the model built in thirds are more common in bebop melodies than arpeggiations within the model built in fourths. 6 The percentages in table 2 illustrate that the major triad in root position is the most employed (61%) of all the arpeggiated major ascending structures. It is used consistently throughout all the improvisations analyzed and is an integral part of Montgomery’s improvisational vocabulary. There are four distinctive techniques illustrated in example 3, regularly used by Wes to improvise with the major ascending triad. Ex.3 Superimpositions of the Major Triad a) b) c) d) The first and most rudimentary technique involves playing an ascending triad starting on the root of the particular chord in the harmonic background. Therefore, on a Bbma7 chord Montgomery improvises an arpeggiated Bb major triad as illustrated in example 3(a). He frequently superimposes a major triad a major second below the tonic of the chord (b), or he may superimpose a major triad a minor third up (c), or a perfect fifth above (d). These different types of melodic superimpositions of major triads over chords will yield distinctively individual sounds and “tonal colors” generated by resulting extensions.10 These extensions are the higher intervals of a chord, that is, the major sevenths, ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths- embellishing notes that have been in use for centuries but 10 Steven Strunk, “Harmony” in The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, op. cit., 485. According to Strunk's definition, “An extended chord is produced when thirds beyond the sevenths are added to the triad (i.e., the ninth, eleventh, thirteenth, etc.). The added notes are normally derived from the diatonic scale of the local key or tonicization....Dominant sevenths are particularly subject to extension.” 7 which play a special role in bebop melodies.11 Jeff Pressing explains the distinctively characteristic usage of these extensions in modern jazz: In Jazz, higher extensions of a chord (9th, 11th, 13th) may be used melodically as stable tones, i.e., function as consonant. In Western art music of the tonal era, this is not so. There, the ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth are almost invariably the result of non-harmonic melodic figuration, at some structural level of the piece, in the Schenkerian sense. That is, extensions higher than 7nth are approached and/or left by step. Jazz frequently uses these higher extensions in this way, but also incorporates them in clearly chord-related (disjunct) riffs....12 In this study the terms “chordal extension” and “superimposition” are used along with numerical designations for these tones when they are explained as arising from superimposed thirds over the chord root.13 The use of tensions (or extensions) is one of the strongest characteristics of bebop melodic lines and chord voicings noticeable in Montgomery’s improvisations. Table 3 reveals that Montgomery uses superimpositions of the tonic, the major second down, and minor third up triads most frequently. The tonic triad outlines Table 3 Triad Superimpositions of the Major Triad Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees tonic 31% d7(21%), M7(79%) R-3-5 maj.2 down 27% d7(83%), m7(17%) 7-9-11 11 Steven Strunk, “Bebop Melodic Lines: Tonal Characteristics,” op. cit., 97. 12 Jeff Pressing, “Towards an Understanding of Scales in Jazz,” Jazzforschung/ Jazz Research, Vol. 9 (1977), 28. 13 Ibid., 97-98. Strunk adds that, “these notes generally behave as melodic, not harmonic events.” In order to separate these pitches from the vertical concept of chordal extension, Strunk refers collectively to these and certain other tones as tensions, defined as follows: “In a tonal diatonic setting, a tension is a pitch related to a structurally superior pitch (usually a chord tone) by step, such that the tension represents and substitutes for the structurally superior pitch, called its resolution, in the register in which it occurs. Most tensions are located a step above their resolutions. The concept of tension is broader than that of suspension, appoggiatura, passing tone, or neighbor tone, as there is no requirement of manner of approach, manner of leaving, or rhythmic position in its definition.” 8 min.3 up 33% d7(12%), m7(88%) 3(b3)-5-7 perfect 5 up 7% M7 (100%) 5-7-9 other 2% m7 (100%) #3-#5-#7 mostly major seventh chords (79% of the time). Whereas the major second triad (down) is generally superimposed melodically over dominant seventh chords (83%) yielding the scale degrees 7, 9, 11 (extensions 9, 11 in italic).14 It is important to notice that the “thirteenth”15 never occurs as an extension when Montgomery improvises with the major ascending structures. Furthermore, the use of the natural eleventh degree as an extension over dominant chords is an idiosyncratic Montgomerian trait. In his discussion of possible superimpositions on the various types of seventh chords in jazz, Jerry Coker proposes the use of the sharp eleventh (#11) after the ninth on dominant chords.16 This is due to the fact that the third and the eleventh do not normally occur simultaneously on dominant chords in jazz.17 However, Montgomery’s syntax clearly displays the widespread use of the diatonic eleventh18 as an extension when using arpeggiated structures. He also employs the sharp eleventh less frequently, however, it usually appears in more linear melodic lines. This is a distinctively Montgomerian trait since most modern jazz improvisers customarily employ the sharp eleventh. In his discussion of modern jazz (bebop) Leonard Feather confirms this: ... you will be impressed with the change that has been effected in the whole character and sound of jazz improvisation by the acceptance of this flatted fifth (#11) as a “right” note instead of a wrong one. When you reflect what a large proportion of chords in any jazz number are sevenths, (or ninths) and how many 14 The seventh in a dominant chord is not considered an extension because it is a functional note, a requisite in a dominant-type chord. 15 The term thirteenth is used when the associated seventh is not major. 16 Jerry Coker, Improvising Jazz (New York: Simon and Schuster, Inc., 1964), 54. 17 Pressing, op. cit., 29. 18 Ibid., 63. The ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth are considered diatonic or unaltered extensions because they can be found within the scale that accompanies that chord. 9 variations can be produced by the inclusion of the flatted fifth in your ad-libbing on each of these chords, you may understand why the flatted fifth has become practically synonymous with bebop.19 The minor third up triad is customarily superimposed over the minor seventh chord (88%) producing the scale degrees 3, 5, 7. Moreover, when Montgomery superimposes this same triad over a dominant seventh chord (12%) there is a clash between the third of the dominant chord and the resulting superimposed scale degree (b3) as illustrated in example 4. The Gb is in conflict with G, the third of the Eb7 chord. Considering Montgomery’s strong propensity for the blues idiom,20 this flatted third (Gb) is simply a blue-note21 that Montgomery employs randomly and regularly throughout all his solos. It is not uncommon for blue notes and unaltered examples of the same degrees to occur within one phrase.22 Occasionally, the two are superimposed as in example 4 and the blue note functions as a type of suspended appoggiatura.23 Ex.4 Satin Doll (m.22) 19 Leonard Feather, Inside Jazz (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1980), 70. 20 Reno De Stefano, “The Blues in Wes Montgomery’s Compositional and Improvisational Style” (M.A. thesis, Université de Montréal, 1990). 21 Mark C. Gridley, Jazz Styles: History and Analysis, 4rth ed. (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1991), 371. Certain writers employ the term “blue note” to designate any pitch that is not entirely a half step below another. This makes its classification “indeterminate” on account of the fact that it is not a clearly identifiable note of the chromatic scale. These are pitches we might find in the cracks between the keys of the keyboard so to speak. Musicologists variously call them “neutral thirds”, “heptatonically equidistant” or “indeterminate pitches.” However, it has now become common practice in the jazz language to refer to the b3, b7 and b5 as blue notes . 22 André Hodeir, Jazz: Its Evolution and Essence, trans. David Noakes (New York: Grove Press, 1956), 155. 23 Ibid., 155. Hodeir affirms that, “the real resolution of these appoggiaturas would be- and actually is, more often than not, in actual performance- not on the degrees just below them, but on the dominant and the tonic, which are the actual magnetic poles of the blue notes.” 10 Table 3 also exhibits Montgomery’s melodic superimposition of the major triad a perfect fifth up, solely on major seventh chords (7%) generating the scale degrees 5, 7, 9. The triads under the heading “other” (2%) produce the tensions (#3-#5-#7). These awkward tensions occur because Montgomery superimposes a major triad a major third above the actual harmonic background. It is a common device of bebop and its parent styles to suggest this half tone raise (of the third, fifth and seventh) without having the rhythm section play it. It is the resolution into the regular key which makes the overall phrase harmonious.24 In example 5, instead of using a Db triad (Db, F, Ab which would correspond to the third, fifth and seventh) over the Bbm7 chord, Montgomery momentarily superimposes the D triad which resolves immediately into the regular key by way of subsequent tones. Ex.5 Airegin (m.53) Excluding this nominal percentage (2%), the table systematically evidences that Montgomery does not ordinarily employ ascending triads to elicit altered extensions over a predetermined harmonic pattern. The generated extensions are most usually of the diatonic type. 24 Feather, op. cit., 53. 11 The analyses indicate that the four-note ascending major arpeggio is used sparingly.25 Due to the evident structural similarity it has with the ascending major triad previously discussed, it is not surprising that Montgomery employs this structure in much the same way. He also makes infrequent use of the first and second inversions of the major ascending triad.26 Montgomery’s second inversion (6/4) chordal superimpositions are quite unique because it is with ascending structures such as these that he produces what is known as “polychordalism”27 or “polytonality,”28 which is the simultaneous playing of two (or more) different chords. In example 6 Montgomery melodically superimposes a major ninth, augmented eleventh, and thirteenth over a C7 chord. These extensions (D, F#, A) outline a D triad that is superimposed over the C7. According to Coker, “we are no longer thinking in terms of ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths, but are involved instead with polychordalism”.29 30 Ex.6 Missile Blues (m.29) 25 On account of the limited reoccurrence of this particular structure, we cannot satisfactorily formulate a comprehensive statistical table. Throughout the study we refrain from using tables or percentages where there appears to be a sparse manifestation of specific structures. 26 We call these inversions 6/3 and 6/4 respectively. 27 Coker, op. cit., 67. 28 Feather, op. cit., 71. 29 Coker, op. cit., 67-68. Coker also gives a multitude of acceptable major and minor triads over the four families of seventh chords. (that is, tonic major, tonic minor, minor seventh, and dominant seventh) 30 Joseph William Rohm, “Jazz Harmony: Structure, Voicing and Progression” (Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University, 1974), 14. Concerning polychords Rohm states, “Multiple extensions of the basic structure (C7 in this case) are sometimes sufficient to create a second chord (D major) above the basic structure. The result is the simultaneous combination of two different chords, a polychord. A polychord may also occur as a combination of extensions and chord tones.” 12 Ex.7 Something Like Bags (m.44) In example 7 Montgomery employs polychordalism melodically over an Fm7 chord. The superimposition of the arpeggiated G major (6/4) over the Fm7 will invariably produce the extensions 9, #11, and 13 as displayed in this example. Superimposing this major triad over a minor seventh chord is somewhat peculiar because the resulting sharp eleventh (B) clashes with the fifth (C) of the Fm7 chord.31 However, Montgomery ingeniously creates momentary melodic tension with this dissonant tone (B), only to resolve it to Bb in the next measure. The six collected samples of this type of ascending major structure are also subjected to the four main superimpositions discussed earlier in example three. 31 Dan Haerle, The Jazz Language (Ind: Studio 224, 1980), 18. According to Haerle, the 11th scale degree is raised in the major and dominant 13th chords. This is generally understood to be necessary to avoid a clash of the natural 11th and the third of the chord. Therefore, the minor 13th chord requires no alteration of the eleventh since the third is lowered and no clash occurs. 13 Table 4 Superimpositions of The Descending Major Triad Triad Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees tonic 23% d7 (100%) R-3-5 maj.2 down 34% d7(62%), m7(38%) 7-9-11 min.3 up 21% m7 (100%) 3-5-7 perfect 4 up 8% d7, m7, M7 R-11-13 perfect 5 up 5% M7 5-7-9 other 7% d7 varied Table 4 illustrates the use of the four basic superimpositions discussed earlier in our analysis of ascending major arpeggios. The recurrence of these superimpositions with the descending structures only confirms our hypothesis that these techniques are integral to Montgomery’s syntax. We can see that Montgomery also employs the superimposition of the perfect fourth with the descending major structures. As illustrated in example 8, this superimposition is utilized equally over dominant, minor seventh, major seventh chords, and is characteristic only of descending arpeggios. Ex.8 Four on Six(m.35) Pretty Blue(m.2.) Midnight Mood(m.29) The extensions eleventh and thirteenth are generated from this particular superimposition. As mentioned earlier, the thirteenth is a common extension used by 14 modern jazz musicians on all three chord types. However, the distinctive employment of the natural eleventh on dominant and major seventh-type chords is quite uncommon in modern jazz. Moreover, this particular form of superimposition only reaffirms our hypothesis concerning Montgomery’s intrepid use of the natural eleventh. We discover that with descending major structures, the natural eleventh is not only used on dominant chords, but on major seventh chords as well, and this with even greater frequency.32 Table 5 Descending Major Chord Structures Structure Type Occurrences Major triad (5/3) 55% 5/3 four-note 3% 6/3 triad 4% 6/3 four-note 1% 6/4 triad 26% 6/4 four-note 11% Table 5 illustrates Montgomery’s infrequent use of the 5/3 four-note (3%), the 6/3 triad (4%), and the 6/3 four-note arpeggiated structures. The descending 6/4 triad (26%) and 6/4 four-note (11%) are more integral to Montgomery’s grammar. This structure is almost always exclusively employed with the first four basic superimpositions in table 3 (excluding the perfect fifth superimposition). The five basic Montgomerian superimpositions of the major ascending triad listed in table 3 are also commonly employed with the 6/4 structure. Notice that these recurring superimpositions produce diatonic and not altered extensions. However, in example 9 32 Although the natural eleventh clashes with the third of the dominant and major seventh chords, it is not overtly conflicting because of the fast speeds at which these improvisations are performed. 15 Montgomery superimposes a Gb 6/4 arpeggiated structure over an Fm7 chord creating the extensions b9, 11, b13. On a superficial level one notices that this improvised line comprises the dissonant tones b9 and b13 which are not commonly used in jazz over minor seventh type chords. Coker for example, suggests that the b9 should not be used on a minor seventh chord.33 There is a transitory clash between the fifth (C) of the Fm7 chord and the flat thirteenth (Db) in this measure. One may wonder why Montgomery approaches this harmony in such a radical a manner. This question is justifiable since he customarily employs chord superimpositions to generate diatonic extensions. Furthermore, we have observed that his use of altered extensions is always accompanied by immediate resolutions. The resolutions in example 9 are not evident. To understand the harmonic implications of this complex melodic line, the analyst must scrutinize deeper into the tradition from which this vocabulary originated. Ex.9 Something Like Bags (m.45) In the introduction we alluded to the fact that Montgomery inherited from his predecessors of the bop movement, a more complex use of chordal extensions and substitutions that intensified the harmonic fabric. The analyst must first attempt to detect within the improvised line, possible harmonic implications not necessarily delineated by 33 Coker, op. cit., 64. 16 the rhythm section. In example 9 the rhythm section plays Fm7 while Montgomery improvises the complex melodic line under discussion. Example 10 clarifies the harmonic implications of the line because it displays the chords (in parentheses) that Montgomery substitutes for the Fm7. Notice that the improvised line clearly outlines the substitute progression Ebm7-Ab7, a IIm-V7 progression preparing the arrival of the Db7. According to Henry Martin, “the IIm7-V7-I harmonic pattern is commonly found in mainstream jazz, especially bop.”34 Dan Haerle adds that, “The II-V-I progression is one of the strongest and most common combinations of chords in jazz harmony. Many bebop tunes are composed using only chords which can be analyzed as either a II, V, or I chord in some major or minor key.”35 Furthermore, chord substitution was a practice that also became prevalent during this era. In his discussion of the bop period Collier states: A second change was the regular use of substitute chords by the players at Minton’s. This is hardly a complex idea: you simply replace a chord, or group of chords, in a song with different, but related ones. Hawkins had been doing this sort of thing for a decade, and Tatum even longer. Again, the difference was that the bop players made a regular practice of it.36 Ex.10 Something Like Bags (m.45) 34 Henry Martin, “Jazz Harmony: A Syntactic Background,” Annual Review of Jazz Studies, Vol. 4 (1988), 10. 35 Haerle, op. cit., 15. 36 Collier, op. cit., 351. 17 In example 10 Montgomery not only arpeggiates the substitution (Ebm7-Ab7) but also employs fundamental voice-leading37 procedures to resolve melodic tension. The seventh (Db) of Ebm7 resolves to the third (C) of Ab7b9, and the seventh (Gb) of Ab7b9 resolves to the third (F) of Db7. The application of this seven to three motion in the melodic line develops logical voice-leading and is essential in outlining V-I chord progressions. Wes’ use of these basic principles of traditional harmony enables him to achieve smooth melodic transition between chords during a solo. The analysis displayed in example 10 implies that Montgomery is not actually employing altered extensions. He does, however, harmonically enhance the improvised line with chord substitutions and preparation chords. Minor Structures The analyses of ascending minor structures reveal that Montgomery employs five fundamental superimpositions in his improvised line as illustrated in example 11. The first technique involves playing an ascending triad starting on the root of the particular chord in the harmonic background (a). Montgomery frequently superimposes a minor triad a major second above the tonic of the chord (b), or he may superimpose a minor triad a major third (c) up, or a perfect fifth above (d). The minor sixth superimposition (e) is 37 Schuller, op. cit., 384. Schuller defines voice-leading as, “A term referring to the manner in which various voices in a harmonic progression are placed by the arranger or composer (improviser) or, in a head arrangement, by the individual players. The term is commonly used in all music.” 18 used only a few times. These varying types of melodic superimpositions generate diverse diatonic and altered extensions as exemplified in table 6. Ex.11 Five Superimpositions of the Minor Triad a) Table 6 Triad b) c) d) e) Superimpositions of the Minor Triad Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees tonic 32% m7 (100%) R-3-5 maj.2 up 29% d7 (100%) 9-11-13 maj.3 up 10% M7 (100) 3-5-7 perfect 5 up 24% m7 (64%) d7 (36%) 5-7-9 min. 6 up 3% m7 (50%) d7 (50%) #7-#9-b13 other 2% varied varied Table 6 shows that Montgomery employs the tonic, major second up, and perfect fifth up superimpositions most often in his improvisations. The tonic triad (32%) naturally outlines only minor seventh chords. The major second triad up (29%) is always superimposed melodically over dominant seventh chords. Notice that this specific superimposition produces the diatonic extensions 9, 11, 13. This is, in fact, characteristic 19 of minor ascending arpeggios since the thirteenth never occurs as an extension when Montgomery improvises with superimpositions of the ascending major triad (see table 3). Once again, Wes uses the natural eleventh abundantly as an extension over dominant seventh chords. The 5/3 four-note triad was employed very rarely (2%), and in these sporadic instances it was always applied with the tonic superimposition (a). The minor 6/3 triad (2%) and the 6/3 four-note (0%) were almost non-existent in our analyses. There is extensive use of both the ascending minor 6/4 and the 6/4 four-note structures in the improvisations. Table 7 illustrates that there are many fewer superimpositions of the 6/4 triad than there are of the root-position triad in Montgomery’s improvised line. As in table 6, the tonic superimposition is the most widely used, however, in this instance, the 6/4 structure is employed on dominant and major seventh chords as well. Table 7 Superimpositions of the Minor 6/4 Triad Triad Occurrences tonic 66% Chord Type d7(24%) M7(14%) Scale Degrees R-b3-5 m7(62%) R-3-5 maj.2 down 6% m7 (100%) 7-b9-11 perfect 5 up 28% d7 (100%) 5-7-9 Table 8 Triad Superimpositions of The Descending Minor Triad Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees tonic 16% m7 (100%) R-3-5 min.2 up 5% d7 (100%) 3-b9-b13 maj.2 up 10% m7 (17%) d7 (83%) 9-11-13 min.3 up 14% d7 (70%) M7 (30%) R-3-13 20 maj.3 up 9% M7 (100) 3-5-7 perfect 5 up 41% m7 (50%) d7 (50%) 5-7-9 other 5% varied varied Table 8 illustrates the various superimpositions of the descending minor triad. The perfect fifth superimposition is used most often (41%) and the minor third up superimposition is employed here, however, it was not used in the ascending type. Again, the resulting extensions are of the diatonic type. The first and second inversions of this descending triad and its four-note structure are employed in much the same way. Major Seventh/Major Ninth Structures Ex.12 a) W. C. Blues (m.53) b) Airegin (m.17) c) W. C. Blues (m.90) The ascending major seventh and major ninth structures are employed very frequently in the improvised line. Montgomery consistently uses these structures with the three basic superimpositions illustrated in example 12 (a, b, c,). Table 9 indicates that Wes uses the major seventh arpeggio on the root (a) (13%), superimposed a major second up (c) (33%), and superimposed a minor third up (b) (52%). The percentages of occurrence are almost identical for the ascending major ninth structure illustrated in table 10. The major ninth will naturally yield an additional extension and provide greater tonal color because of its five-note construction (ninth, eleventh and thirteenth). 21 Table 9 Superimpositions of the Ascending Major 7 Structure Triad Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees tonic 13% M7 (100%) R-3-5-7 maj.2 down 33% d7 (100%) 7-9-11-13 min.3 up 52% m7 (100%) 3-5-7-9 other 2% varied varied Table 10 Superimpositions of the Ascending Major 7/9 Structure Triad Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees tonic 13% M7 (100%) 3-5-7-9 maj.2 down 29% d7 (100%) R-7-9-11-13 min.3 up 54% m7 (100%) 3-5-7-9-11 other 4% varied varied Once again, we observe that even with a five-note arpeggiated structure, Montgomery uses extensions that are predominantly diatonic degrees of the scale, and on dominant seventh chords he consistently employs the natural eleventh. Harmonic Anticipations The transcriptions evidence that Montgomery was often inclined to anticipate a chord melodically on the first beat of the measure, especially with major seventh superimpositions. In example 13, Wes anticipates the C minor-seventh chord by superimposing a major seventh structure two beats before its arrival. This technique is 22 remarkably effective because the ninth of the chord coincides with the first beat of the measure resulting in an accentuated “color tone.” The diatonic extensions- ninth (ex.13) and thirteenth (ex.14)- are quite often highlighted on the first beat of a measure in Montgomery’s improvisations.38 Ex.13 Four on Six (m.52) Ex.14 D-Natural Blues (m.12-13) Descending Major7 & Major7/9 Structures 38 Fred Sokolow, Wes Montgomery (Winona, MN: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation, 1988), 5. Sokolow has made similar observations concerning the ninth scale degree. 23 Table 11 illustrates the different types of superimpostions of the descending major seventh structure. Although this descending form is employed less frequently than the ascending one, Wes still favors the minor third up superimposition (63%), followed by the major second down (34%). The tonic superimposition was never employed. The major ninth structure was seldom used (only seven times), however, the minor third superimposition still occurred most frequently. Table 11 Superimpositions of the Descending Major 7 Structure Triad Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees maj.2 down 34% d7 (100%) 7-9-11-13 min.3 up 63% m7 (95%) d7 (5%) 3-5-7-9 other 3% varied varied Minor Seventh Structures Montgomery employs four basic superimpositions of the minor seventh structure in his solos. The root superimpostion (a) is by far, the most widely used structure (60%), followed by the perfect fifth up superimposition (d) (23%) which yields as extensions, the ninth and eleventh. Both the major second up (b) (5%) and major third up superimpositions (c) (7%) are used sparingly. The major second superimposition is the most colorful because its resulting extensions include the ninth, eleventh and thirteenth. Ex.15 Four Superimpositions of The Minor Seventh Structure a) Four On Six (m.51) b) W.C. Blues (m.66) c) Canadian d) Freddie Freeloader Sunset(m.53) (m.43) 24 Table 12 Superimpositions of the Ascending Minor 7 Structure Triad Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees tonic 60% m7 (100%) R-3-5-7 maj.2 up 5% d7 (100%) R-9-11-13 maj.3 up 7% M7 (100%) 3-5-7-9 perfect 5 up 23% d7 (62%) m7 (38%) 5-7-9-11 other 5% varied varied The descending minor seventh structure (table 13) occurs only half as often as the ascending structure. With this particular structure the perfect fifth up superimposition is applied more frequently than the tonic superimposition. The minor third down superimposition is also used here, in addition to the four basic superimpositions illustrated in example 15. Table 13 Triad Superimpositions of the Descending Minor 7 Structure Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees tonic 19% m7 (100%) R-3-5-7 maj.2 up 11% m7 (100%) R-9-11-13 25 min.3 down 11% d7 (100%) R-3-5-13 maj.3 up 22% M7 (100%) 3-5-7-9 perfect 5 up 33% d7 (56%) m7 (44%) 5-7-9-11 other 4% varied varied Minor 7/9 & Minor 7/9/11 Both the minor 7/9 and the minor 7/9/11 structures are used very sparingly and rarely occur in descending fashion. When these structures are employed within the improvised line the most common superimpositions are the perfect fifth up, ex.16 (a), and the tonic superimpositions, ex.16 (b). The percentages have demonstrated that this corresponds to the way in which Montgomery customarily uses most of the minor seventh structures. Because of its six-note construction the minor 7/9/11 (16b) structure often occurs over the bar-line of a measure. The resulting scale degress and extensions are (R, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13 on a perfect fifth up superimposition) or (R, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11 on a root superimposition). Ex.16 (a) Freddie The Freeloader (m.13) (b) D-Natural Blues (m.33) Minor Seventh b5/ Minor Seventh b5/b9/11 Ex.17 a) Four on Six (m.24) b) Four on Six (m.73) c) W.C. Blues (m.40) d) Four on Six (m.43) 26 The analyses evidence that Montgomery uses four-note and six-note halfdiminished (minor7b5) structures mainly in ascending motion. Wes employs two basic superimpositions of this structure. The first superimposition (a major third up, ex.17a and 17c) generates the scale degrees 3, 5, 7, 9, and 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, respectively. The second superimposition (a minor third down, ex.17b and 17d) yields the scale degrees R, 3, 5, 13, and R, 3, 5, 7, 9, 13. In general, this structure is used sporadically. Application of Tone Color Ex.18 Pretty Blue (m.1-3) 27 The first three measures of Montgomery’s solo on Pretty Blue (ex.18) evidence his harmonic command and mastery of the improvised line through the sole use of arpeggiated diatonic extensions. The very first note of the solo is the infamous “Montgomerian eleventh”- Gb, which is the most dissonant of the diatonic extensions because of its half-step proximity to the third of the chord. This Gb is underscored once again on the third beat of the first measure. In the second measure Wes changes tone color and highlights the thirteenth, Bb, four times. This tone is not as dissonant as the eleventh, but it is certainly the most colorful diatonic extension realizable on a dominant seventh chord. By the third measure Wes has moved to the ninth, Eb, which he accentuates on the first beat and thereafter, proceeds to end his first phrase on a fundamental chord tone, Ab. Therefore, within the span of three measures Montgomery has skillfully traversed the diatonic sound spectrum moving systematically from the most dissonant and colorful extensions to a harmonic base at the end of the phrase. Wes uses this technique in the opening measures of several other improvisations.39 Diminished Structures Arpeggiated diminished structures are not used as frequently as the major or minor-type structures, and their superimpositions are quite varied and inconsistent. Consequently, it is impossible to formulate valid conclusions concerning percentages for these types of superimpositions. The data does show, however, that diminished structures often appear to be the result of an arpeggiation of the third, fifth, and seventh degrees of dominant seventh-type chords. Ex.19 Airegin (m.40) Whisper Not (m.28) 39 Refer to Something Like Bags (m.1-5); Cariba (m.1-3). 28 We have observed thus far that superimpositions of disparate types of extended minor and major structures yield for the most part, diatonic extensions in Wes Montgomery’s improvisations. However, with the diminished structures- especially the diminished seventh structure (ex.19), the degrees and extensions generated are the third, fifth, seventh, and the flatted ninth (b9). The structure will always naturally yield the flatted ninth as an altered extension if it is played from the third degree of a dominant seventh chord as in example 19. Augmented Structures Table 14 Triad Superimpositions of the Augmented Structure Occurrences Chord Type Scale Degrees tonic 48% d7 (85%) m7 (15%) R-3-#5 (b13) min.2 down 15% m7 (100%) 3-5-#7 min.3 down 15% d7 (100%) b9-11-13 tritone up 19% d7(60%) m7b5(40%) other 3% varied 7-9-#11/5-7-9 varied 29 Montgomery employs augmented structures in descending motion (79%) more frequently than in ascending motion (21%). The disparate superimpositions displayed in table 14 produce various altered extensions (non-diatonic) which evidently generate dissonances within the improvised line. The aforementioned minor and major-type superimpositions yielded strictly diatonic extensions that became increasingly more colorful when consecutive thirds were superimposed on a harmonic background. With the diminished and augmented-type superimpositions, altered extensions are used to create dissonances and tensions within the melodic line rather than tonal colors. The four most common type of superimpositions of the augmented structure are illustrated in example 20a and b, and example 21a and b. Each superimposition contains one scale degree or extension that is altered (i.e. #5, b9, #7, #11). The #5, b9, #11 are normally used on dominant seventh chords and the #7 on minor chords. Ex.20 a) Missile Blues (m.16) Ex.21 a) Four on Six (m.69) b) Freddie Freeloader (m.80) b) Missile Blues (m.30) 30 The Tri-tone Substitution This technique has become widespread in modern jazz since the advent of bop in the 1940’s, and is one of the various methods used by Wes to create altered extensions in his melodic lines.40 Two dominant seventh chords whose roots are a tri-tone apart share the same third and seventh. Because these two harmonically important notes are present in both chords (the third of one of the chords is the seventh of the other and vice versa), a dominant seventh chord a tri-tone away from another dominant seventh chord may substitute for it (i.e. G7 for Db7). In a II-7 V7 I∆7 progression for instance, we can substitute a chord a tri-tone from V7, creating a II-7 bII7 I∆7 progression. Ex.22 a) C Rain or C Shine (m.38) b) Blue n’ Boogie (chor.6, m.8) In example 22a (Come Rain or Come Shine ) the dominant seventh chord, Bb7, is preceded by its dominant preparation chord, Fm7, nonetheless, the whole measure functions fundamentally as a Bb7 harmony. Montgomery’s improvised line in this measure clearly outlines a E mixolydian scale which is customarily played over a E7 harmony, which is the tri-tone substitution of Bb7. The altered extensions generated by the substitution are C#-#9, B-b9, F#-b13, E-#11. The second part of the phrase starting on 40 Steven Strunk, “Harmony” in The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, op. cit., 494. Strunk provides a historical setting for the development of the tri-tone substitution principle: In the 1940’s “Charlie Parker and his colleagues worked out numerous harmonic innovations, which to a great degree defined the new style:.....they fully explored the possibilities offered by substitute chords, resorting particularly frequently to the dominant seventh structure on the flatted supertonic in place of chord V........” 31 the third beat (E, D, C#, B) plainly outlines the E7 chord. Similarly, in example 22b (Blue n’ Boogie) Montgomery improvises on and clearly arpeggiates Ab7/9, the tri-tone substitution of D7. Wes customarily employs tri-tone substitutions to create harmonic tension and momentary dissonance through non-diatonic tones. Transcriptions show that the vast majority of these phrases are linear and not arpeggiated. Contrapuntal Elaboration of Static Harmony (“Cesh”) This term was first used by the esteemed jazz author-educator, Jerry Coker.41 This particular device is widely used in jazz and it can be found in many standard songs and improvised solos. “Static harmony” indicates that a single chord is played in the harmonic background, while “contrapuntal elaboration” refers to the degree of the chord which is in motion. Coker lists four possible varieties of Cesh, however, “the most common one by far,” which is also employed by Wes, is the minor chord with the root in descending motion.42 In measures 33 to 39 of his solo on Canadian Sunset (ex.23), Wes Montgomery plays three successive sequences of Cesh. The supposed harmonic setting for a Cesh to take place is on a minor chord of long duration. However, many examples from recorded solos will reveal that improvisers will also use Cesh on II-7 chords, V7 chords, or the II-V in combination as Montgomery does in Canadian Sunset.43 Wes particularly favored using Cesh on II-V progressions because the seventh-tosix motion of the II-7 chord (m.33-34) actually functions as a four-three suspension on the V7 (C7), causing momentary tension. This brief suspension resolves immediately on the third, E, of the V7 chord (C7) in measure 34. The same procedure is applied in measure 35-36 over the Am7-(D7) progression. At measures 37-38 Wes employs the same technique, however, the resolution of F (the seventh of Gm7 or the fourth of C7) is 41 Jerry Coker, Elements of The Jazz Language for The Developing Improvisor (Miami: Studio 224, 1991), 61-67. 42 Ibid., 62. 43 Ibid., 63. 32 delayed until the next measure to increase harmonic tension. It is then resolved as the major seventh of the I chord, Fmaj7 (F∆7) in measure 39. Ex.23 Canadian Sunset (m.33-39) Concluding Remarks Wes Montgomery’s individuality and uniqueness as a master jazz improviser is reflected in his distinctively personal use of superimpositions generating both diatonic and altered extensions over varying harmonic backgrounds. The analyses have shown that disparate types of major and minor arpeggiated structures generate predominantly diatonic 33 extensions which imbue the improvised line with the so-called “tonal color” or “tonal shading.” Polychordalism, chord substitutions, tri-tone substitutions, and the varying superimpositions of the diminished and augmented structures, generate mostly altered extensions- the “marvelous use of substitute notes for the harmonic ones.” Moreover, the analyses, classifications, and percentages of occurrence have demonstrated that Montgomery’s usage of superimpositions is not haphazard but systematic, invariable, and an integral part of his musical grammar and syntax. Melodic tension and continuity within the improvised line are also achieved through more commonly used jazz techniques such as the contrapuntal elaboration of static harmony. We have investigated and illustrated some of the fundamental techniques Montgomery employed to create multifarious tonal colors, shadings, and harmonic tensions in the improvised line. The complex nature of the analyses and data obtained, as well as the harmonic sophistication displayed throughout the chapter, could easily lead one to believe that by academic standards, Wes had an extensive knowledge of music theory and harmony. Nothing is further from the truth. Montgomery was basically a selftaught musician who could not read nor write music, nor for that matter, read basic chord symbols. He could, nonetheless, “recognize and speak of them as fluently as most of us can write or speak.”44 The consistent and systematic use of superimpositions and other harmonic techniques evidence that Montgomery had developed a highly individualized and personal musical system that enabled him to play the sounds he heard. This is also revealed in the fact that his approach to the instrument was considered unorthodox and exclusive. So much so, that guitarists posited that Wes appeared to have “no rationalized approach to the fingerboard in the position-playing sense. He knows what musical sounds he wants and he goes for them with ‘anything’ that comes to hand.”45 Whatever his fingerboard approach might have been is beyond the scope of this study. His improvised music does reveal, however, a highly systematized and developed harmonic sense. 44 John W. Duarte, “Wes Montgomery- Natural Genius,” B.M.G., Aug. (1968), 343. 45 John. W. Duarte, “Wes Montgomery,” B.M.G., July (1962), 308