LA Praxis: Language Arts Content

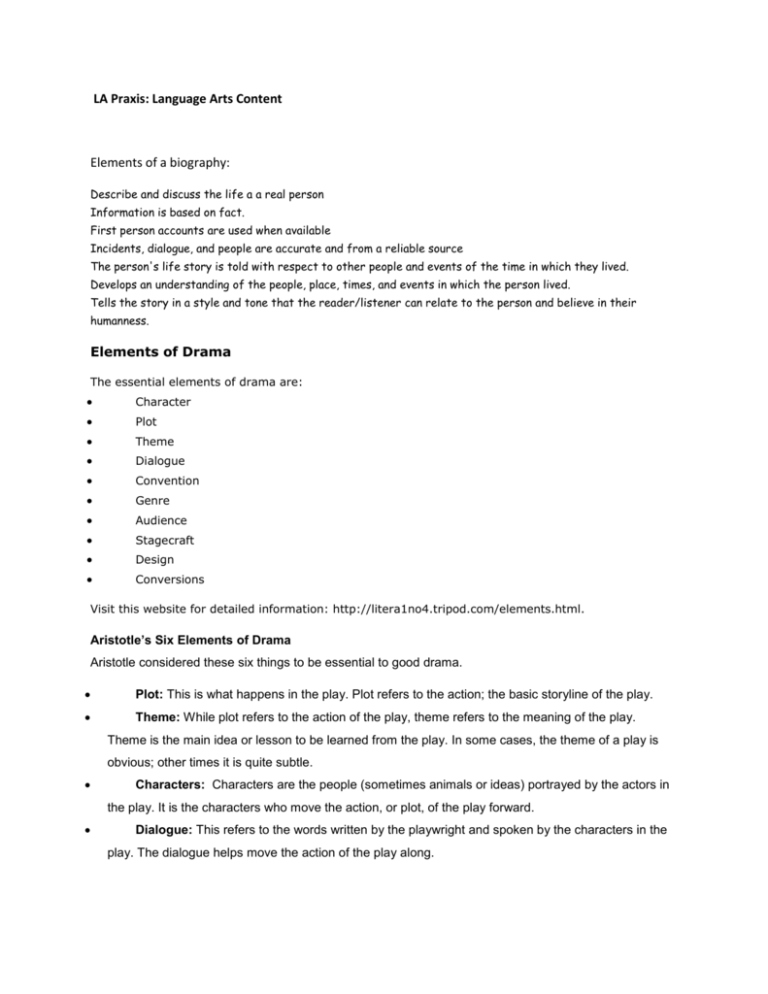

Elements of a biography:

Describe and discuss the life a a real person

Information is based on fact.

First person accounts are used when available

Incidents, dialogue, and people are accurate and from a reliable source

The person's life story is told with respect to other people and events of the time in which they lived.

Develops an understanding of the people, place, times, and events in which the person lived.

Tells the story in a style and tone that the reader/listener can relate to the person and believe in their

humanness.

Elements of Drama

The essential elements of drama are:

Character

Plot

Theme

Dialogue

Convention

Genre

Audience

Stagecraft

Design

Conversions

Visit this website for detailed information: http://litera1no4.tripod.com/elements.html.

Aristotle’s Six Elements of Drama

Aristotle considered these six things to be essential to good drama.

Plot: This is what happens in the play. Plot refers to the action; the basic storyline of the play.

Theme: While plot refers to the action of the play, theme refers to the meaning of the play.

Theme is the main idea or lesson to be learned from the play. In some cases, the theme of a play is

obvious; other times it is quite subtle.

Characters: Characters are the people (sometimes animals or ideas) portrayed by the actors in

the play. It is the characters who move the action, or plot, of the play forward.

Dialogue: This refers to the words written by the playwright and spoken by the characters in the

play. The dialogue helps move the action of the play along.

Music/Rhythm: While music is often featured in drama, in this case Aristotle was referring to the

rhythm of the actors' voices as they speak.

Spectacle: This refers to the visual elements of a play: sets, costumes, special effects, etc.

Spectacle is everything that the audience sees as they watch the play.

In modern theater, this list has changed slightly, although you will notice that many of the elements

remain the same. The list of essential elements in modern theater are:

Character

Plot

Theme

Dialogue

Convention

Genre

Audience

The first four, character, plot, theme and dialogue remain the same, but the following additions are now

also considered essential elements of drama.

Convention: These are the techniques and methods used by the playwright and director to

create the desired stylistic effect.

Genre: Genre refers to the type of play. Some examples of different genres include, comedy,

tragedy, mystery and historical play.

Audience: This is the group of people who watch the play. Many playwrights and actors

consider the audience to be the most important element of drama, as all of the effort put in to writing

and producing a play is for the enjoyment of the audience.

Elements of an epic poem

An epic poem is a long poem narrating the heroic

exploits of an individual in a way central to the

beliefs and culture of his society. Typical elements are

fabulous adventures, superhuman deeds, polyphonic

composition, majestic language and a craftsmanship

deploying the full range of literary devices,

from lyrical todramatic. Nonetheless, the first epics —

Iliad,Odyssey, Mahabharata, Ramayana — were

created and transmitted orally, a tradition still seen

in Serbian guslars and storytellers throughout Asia.

Being so demanding, epic poetry is counted among man's noblest

creations. Gilgamesh,Mahabharata, Ramayana, Iliad, Odyssey,Aeneid, Beowulf, Poema de mio Cid, La Chanson de

Roland, Divine Comedy, Jerusalem Delivered,Orlando Furiosa, os Lusíadas, Faerie Queen, andParadise Lost are still read

with admiration and enthusiasm. Some long poems are better called mock heroic or satire — The Rape of Lock, Don

Juan, — and others are magnificent failures:Prelude, Hyperion, Idylls of the King, Cantos,There is also the pastoral

tradition, fromTheocritus through Virgil to Milton and others, but the setting is an idealised landscape and the heroic

element is missing.

The Elements and Structure of a Formal Essay

In this class, we will be asking you to use the writing process to write

formal, college level essays. Formal essays must have five basic elements

if they are to be successful:

1. A strong thesis statement with logical supporting points.

2. Body paragraphs that discuss the supporting points in the order

they are mentioned in the thesis statement.

3. Good transitions between paragraphs.

4. A conclusion which summarizes what has been said in the body of

the paper.

5. Appropriate diction and tone.

These five elements are absolutely essential. We will be grading your

papers on whether or not the five elements are present. Each of these

elements is discussed below. At the end of this document is an outline

and brief description of standard essay structure.

1. The Thesis Statement

As you learned from the “Reader as Writer” reading, a thesis is a statement

of fact or opinion that you will defend in the course of your paper. The

thesis statement includes the reasons or points you will be making to

support your initial statement. A thesis statement does two vitally important

things. 1) it establishes the subject and purpose of your paper, 2) it gives

your readers a roadmap of the points that will be discussed in the paper.

Here is an example of an effective thesis statement:

Overall, online learning offers many advantages to a diverse

array of students. Disabled students, adults returning to school

and rural students all benefit greatly from online learning.

Online learning does not come without problems though.

Computers can crash and servers can go down. Dealing with

these problems can be time consuming and frustrating.

Cindy’s paragraph is effective because it states the writer’s opinion (online

learning offers many advantages to a diverse array of students, but online

learning does not come without problems) and her reasons for this

opinion. In the body of her essay, the author went on to discuss in detail 1)

advantages to disabled students; 2) advantages to returning adult

students; 3) advantages to rural students; 4) disadvantages to all students.

Thus, her thesis served as a very effective roadmap for what was to come

in the essay.

Here is an example of an ineffective thesis statement:

I enrolled in my first online computer class this summer. So far I

learned that there are definitely some disadvantages and

advantages of an online class. I feel that I need the interaction

that you get with a usual classroom environment. I like to know

how I'm doing in the class, being able to have questions

answered right away, and meeting my fellow students. I guess

that I am a people person and like the interaction that a

classroom has to offer.

John’s paragraph is ineffective because the reader has no idea what the

author is going to discuss in the paper. Each sentence is a possible topic,

but there is nothing to indicate how the ideas connect to one another, which

ideas are important, or what points the author is going to use to support his

ideas. (Top of Page)

2. Body Paragraphs

As noted above, your body paragraphs need to directly and specifically

discuss the points mentioned in your thesis statement in the order they

are mentioned in your thesis statement. If you don’t do this, your

roadmap isn’t just invalid, it’s misleading, and your readers will become

confused.

When you write the body of your paper, you should always be looking back

at your thesis to see that you’re following the roadmap. If, as you’re writing,

you think of another point it’s important and logical to make, you need to

revise your thesis so that the roadmap is still valid.

A body paragraph takes a point –for example, advantages of online

learning for disabled students—and discuss it in detail, giving examples

and evidence to support that point. Here’s Cindy’s body paragraph on

advantages of online learning for disabled students:

Disabled students are one group of people who benefit greatly

from online learning. Many disabled students face great

obstacles when trying to receive a college education. Just

getting to school can be difficult and expensive. Many schools

do not have specialized computer programs that can help blind

or deaf students. Though schools are now required to provide

sign language interpreters for deaf students, many still miss

things that are discussed in class. Schools are often large,

making it hard for some students to even get to the classrooms.

With online learning, disabled students no longer have to worry

about these things. They are now on the same level as

everyone else.

You see how Cindy has given us examples and reasons why online

learning is advantageous for the disabled. Notice how in her thesis she

simply lists the disabled as one of the groups that benefit from online

learning. She uses the body paragraph to discuss this point in depth and

provide evidence to support it. (Top of Page)

3. Transitions

Providing logical connections between ideas is one of the most important

keys to good writing. If you and I are talking about how uncomfortable the

hot weather has been, and all of a sudden I say “Lobo, my pet slug died,”

you’re going to be completely confused. You won’t know how I got from

the weather to the tragic death of Lobo. What’s missing is the transition,

the thought that links one idea to the next.

Let’s say, on the other hand, that we’re talking about the hot weather, and I

remark “The hot weather isn’t just uncomfortable; it’s dangerous too. In

fact, Lobo my pet slug, insisted on going outside for his daily walk and he

died of heat prostration in two minutes flat.” I’ve built a bridge between the

two ideas with one simple sentence that connects the old idea (hot weather

is uncomfortable) with the new idea (hot weather is dangerous).

The good news about transitions is that they don’t have to be

complicated. They can be as simple as one word or a single

sentence. You just need to be sure that as you read over your paper you

ask yourself what the connection between each of your ideas is. For a list

of good transition words, see the “Paragraphs” document in the “Grammar”

folder under Course Documents. (Top of Page)

4. The Conclusion

It is said that “A conclusion is the place where you got tired of

thinking.” However, this is not supposed to be the case in your

essays. Your conclusion serves two specific functions: 1) it summarizes

what has been said in the body of the paper without repeating it, and 2) it

provides the reader with a relevant final thought on what you want them to

do, think, believe, or understand, now that they've read your essay. Note

that a conclusion is definitely not the place to introduce new ideas.

Here’s a case study of a good conclusion. Maureen was writing about the

positive and negative aspects of online communities. Her thesis statement

was:

Having a virtual classroom as the sole source of instruction is a

growing trend with several wonderful advantages. We can have

discussion where each person’s contribution is uninterrupted,

where gender is not necessarily a factor, where appearances

does not distract us and where many disabilities are no longer a

barrier. There is potential for misunderstanding, false identities,

magnified emotions, and information overload, but the

advantages balance the negatives to make virtual classrooms a

welcome addition to our educational system.

In the body of her paper, Mo discussed the points she raised, setting an

optimistic tone both about the advantages and about the fact that problems

with online classes were resolvable. Her conclusion ties these ideas

together, reminds the reader of thesis without repeating it, and leaves the

reader with a relevant final thought.

As virtual classrooms and our educational systems evolve into

the mainstream, we will need to find the balance between the

advantages and challenges of this new forum for education.

The difficulties the online environment poses do not outweigh

its advantages, particularly since there are solutions to many of

these problems. Ultimately, the fact that education is growing

to include the internet as a standard learning option means we

will have another forum for people to flourish and develop in

their intellect and ability. This is a wonderful opportunity that will

benefit us all.

Notice that Mo hasn’t added any new ideas or arguments in her

conclusion. If you get to the end of your paper and say “Oh! I just thought

of another thing,” do not tack it on to the conclusion. As stated above,

“When you write the body of your paper, you should always be looking

back at your thesis to see that you’re following the roadmap. If, as you’re

writing, you think of another point it’s important and logical to make, you

need to revise your thesis so that the roadmap is still valid.”

Anna’s pet peeve: do not cheat by using the words “in conclusion” to

announce the arrival of your conclusion. The content of your concluding

paragraph should make clear that it is in fact the conclusion without you

having to say it. (Top of Page)

5. Appropriate Diction and Tone

The purpose of this class is to teach you how to write formal, college level

essays. Part of writing these essays is learning the diction (word choice)

and tone customary in this kind of writing. Here are some guidelines for the

appropriate diction and tone of your essays. Note that these guidelines do

not apply to the other kinds of writing you do in this class.

You are writing for an audience of classmates and teachers.

You are speaking to these people in a professional or formal

capacity, as opposed to a casual and friendly capacity (such as we

use in our chat room or email exchanges). Imagine you are dressed

in your nicest clothes and speaking to an audience that has come to

hear you and learn something from you.

Your audience has a basic understanding of your topic and does not

need common or simple terms explained to them.

You should not use slang or informal language in them. One of the

problems with John’s thesis statement in the Thesis section above is

that tone is much to informal.

Your focus should be on facts and ideas rather than rumor and

conjecture.

You should not include “I believe,” “I think,” “I feel,” “In my opinion,”

etc. in your essay. It is assumed that an essay represents your ideas

and opinions. These are useless fillers. Don’t believe me? Try

crossing those phrases out, and you’ll find your sentence works just

as well without them. Note: it’s perfectly fine for you to discuss your

own specific experiences (“Once when I was in a chat room, I had a

five hour conversation with someone about snails.”)

Do not use any version of the phrase “It goes without saying.” If

something goes without saying, your reader will wonder why you are

bothering to say it. You should wonder too. The same goes for “not to

mention.”

Avoid rhetorical questions like “How would you like to . . .” or “What

do you think of that?” These direct addresses to an audience set an

informal, “talky,” tone and don’t actually accomplish anything but

taking up space (since, of course) your audience cannot answer you.

(Top of Page)

Standard Essay Structure

Here’s an overview of how a standard essay is structured. Just something

to keep in mind as you work on formulating your thesis and start thinking

about writing your rough draft.

I. Thesis (A statement of opinion that you will discuss and defend in your

essay)

Example: As more and more people integrate the internet into their work

and private lives, we will see a dramatic increase in both written and verbal

communication skills.

A. Sub Point #1 (Sub points break the thesis down into parts which

you will then discuss at greater length in the body of the paper. Sub

points serve the reader as a road map to the organization of your

paper.)

Example: Writing skills naturally improve with internet use, since almost all

online communication is conducted through the written word.

B. Sub Point #2

Example: In addition, while internet users become more proficient at

writing, their spoken communication skills will also improve, because

writing will give them practice organizing and expressing their ideas.

(Note: you may have more than two sub points)

II. Body

A. Discussion of Sub Point #1

Explain this idea in more detail.

Raise possible objections, problems with this idea.

Answer these objects and defend this idea.

B. Discussion of Sub Point #2

Explain this idea in more detail.

Raise possible objections, problems with this idea.

Answer these objectionss and defend this idea.

Discussion of further Sub Points if you have listed them in your

thesis.

III. Conclusion

Your conclusion restates your thesis (puts it in different words), and leaves

the reader with a relevant final thought on what you want the reader to do,

think, believe, or understand, now that they've read your essay.

History (from Greek ἱστορία - historia, meaning "inquiry, knowledge acquired by investigation"

[2])

is

the study of the human past, with special attention to the written record. Scholars who write about history

are called historians. It is a field of research which uses a narrative to examine and analyse the sequence

of events, and it often attempts to investigate objectively the patterns of cause and effect that determine

events.[3][4] Historians debate the nature of history and its usefulness. This includes discussing the study

of the discipline as an end in itself and as a way of providing "perspective" on the problems of the

present.[5][3][6][7] The stories common to a particular culture, but not supported by external sources (such

as the legends surrounding King Arthur) are usually classified as cultural heritage rather than the

"disinterested investigation" needed by the discipline of history.[8][9]

Literary Terms

Aesthetic distance: degree of emotional involvement in a work of art. The most obvious

example of aesthetic distance (also referred to simply as distance) occurs with paintings. Some

paintings require us to stand back to see the design of the whole painting; standing close, we see

the technique of the painting, say the brush strokes, but not the whole. Other paintings require us

to stand close to see the whole; their design and any figures become less clear as we move back

from the painting.

Similarly, fiction, drama, and poetry involve the reader emotionally to different degrees.

Emotional distance, or the lack of it, can be seen with children watching a TV program or a

movie; it becomes real for them. Writers like Faulkner, the Bronte sisters, or Faulkner pull the

reader into their work; the reader identifies closely with the characters and is fully involved with

the happenings. Hemingway, on the other hand, maintains a greatr distance from the reader.

Alliteration: the repetition of the same sound at the beginning of a word, such as the repetition

of b sounds in Keats's "beaded bubbles winking at the brim" ("Ode to a Nightingale") or

Coleridge's "Five miles meandering in a mazy motion ("Kubla Khan"). A common use for

alliteration is emphasis. It occurs in everyday speech in such prhases as "tittle-tattle," "bag and

baggage," "bed and board," "primrose path," and "through thick and thin" and in sayings like

"look before you leap."

Some literary critics call the reptition of any sounds alliteration. However, there are

specialized terms for other sound-repetitions. Consonance repeats consonants, but not the

vowels, as in horror-hearer. Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds, please-niece-ski-tree.

See rhyme.

An allusion: a brief reference to a person, event, place, or phrase. The writer assumes will

recognize the reference. For instance, most of us would know the difference between a

mechanic's being as reliable as George Washington or as reliable as Benedict Arnold. Allusions

that are commonplace for readers in one era may require footnotes for readers in a later time.

Ambiguity: (1) a statement which has two or more possible meanings; (2) a statement whose

meaning is unclear. Depending on the circumstances, ambiguity can be negative, leading to

confusion or even disaster (the ambiguous wording of a general's note led to the deadly charge of

the Light Brigade in the Crimean War). On the other hand, writers often use it to achieve special

effects, for instance, to reflect the complexity of an issue or to indicate the difficulty, perhaps the

impossibility, of determining truth.

The title of the country song "Heaven's Just a Sin Away" is deliberately ambiguous; at a

religious level, it means that committing a sin keeps us out of heaven, but at a physical level, it

means that committing a sin (sex) will bring heaven (pleasure). Many of Hamlet's statements to

the King, to Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern, and to other characters are deliberately ambiguous,

to hide his real purpose from them.

Ballad: a relatively short narrative poem, written to be sung, with a simple and dramatic action.

The ballads tell of love, death, the supernatural, or a combination of these. Two characteristics of

the ballad are incremental repetition and the ballad stanza. Incremental repetition repeats one or

more lines with small but significant variations that advance the action. The ballad stanza is four

lines; commonly, the first and third lines contain four feet or accents, the second and fourth lines

contain three feet. Ballads often open abruptly, present brief descriptions, and use concise

dialogue.

The folk ballad is usually anonymous and the presentation impersonal. The literary

ballad deliberately imitates the form and spirit of a folk ballad. The Romantic poets were

attracted to this form, as Longfellow with "The Wreck of the Hesperus," Coleridge with the

"Rime of the Ancient Mariner" (which is longer and more elaborate than the folk balad) and

Keats with "La Belle Dame sans Merci" (which more closely resembles the folk ballad).

Characterization: the way an author presents characters. In direct presentation, a character is

described by the author, the narrator or the other characters. In indirect presentation, a character's

traits are revealed by action and speech.

Characters can be discussed in a number of ways.

The protagonist is the main character, who is not necessarily a hero or a heroine.

The antagonist is the opponent; the antagonist may be society, nature, a person, or an

aspect of the protagonist. The antihero, a recent type, lacks or seems to lack heroic traits.

A persona is a fictional character. Sometimes the term means the mask or alter-ego of

the author; it is often used for first person works and lyric poems, to distinguish the writer

of the work from the character in the work.

Characters may be classified as round (three-dimensional, fully developed) or as flat

(having only a few traits or only enough traits to fulfill their function in the work); as

developing (dynamic) characters or as static characters.

A foil is a secondary character who contrasts with a major character; in Hamlet, Laertes

and Fortinbras, whose fathers have been killed, are foils for Hamlet.

Convention: (1) a rule or practice based upon general consent and upheld by society at large; (2)

an arbitrary rule or practice recognized as valid in any particular art or discipline, such as

literature or art (NED). For example, when we read a comic book, we accept that a light bulb

appearing above the head of a comic book character means the character suddently got an idea.

Literary convention: a practice or device which is accepted as a necessary, useful, or

given feature of a genre, e.g., the proscenium stage (the "picture-frame" stage of most

theaters), a soliloquy, the epithet or boast in the epic (which those of you who took Core

Studies 1 will be familiar with).

Stock character: character types of a genre, e.g., the heroine disguised as a man in

Elizabethan drama, the confidant, the hardboiled detective, the tightlipped sheriff, the girl

next door, the evil hunters in a Tarzan movie, ethnic or racial stereotypes, the cruel

stepmother and Prince Charming in fairy tales.

Stock situation: frequently recurring sequence of action in a genre, e.g., rags-to-riches,

boy-meets-girl, the eternal triangle, the innocent proves himself or herself.

Stock response: a habitual or automatic response based on the reader's beliefs or

feelings, rather than on the work itself. A moralistic person might be shocked by any

sexual scene and condemn a book or movie as dirty; a sentimentalist is automatically

moved by any love story, regardless of the quality of the writing or the acting; someone

requiring excitement may enjoy any violent story or movie, regardless of how mindless,

unmotivated or brutal the violence is.

Fiction: prose narrative based on imagination, usually the novel or the short story.

Genre: a literary species or form, e.g., tragedy, epic, comedy, novel, essay, biography, lyric

poem. Click here for a fuller discussion of genres.

Irony: the discrepancy between what is said and what is meant, what is said and what is done,

what is expected or intended and what happens, what is meant or said and what others

understand. Sometimes irony is classified into types: in situational irony, expectations aroused

by a situation are reversed; in cosmic irony or the irony of fate, misfortune is the result of fate,

chance, or God; in dramatic irony. the audience knows more than the characters in the play, so

that words and action have additional meaning for the audience; Socractic irony is named after

Socrates' teaching method, whereby he assumes ignorance and openness to opposing points of

view which turn out to be (he shows them to be) foolish. Click here for examples of irony.

Irony is often confused with sarcasm and satire:

Sarcasm is one kind of irony; it is praise which is really an insult; sarcasm generally

invovles malice, the desire to put someone down, e.g., "This is my brilliant son, who

failed out of college."

Satire is the exposure of the vices or follies of an indiviudal, a group, an institution, an

idea, a society, etc., usually with a view to correcting it. Satirists frequently use irony.

Language can be classified in a number of ways.

Denotation: the literal meaning of a word; there are no emotions, values, or images

associated with denotative meaning. Scientific and mathematical language carries few, if

any emotional or connotative meanings.

Connotation: the emotions, values, or images associated with a word. The intensity of

emotions or the power of the values and images associated with a word varies. Words

connected with religion, politics, and sex tend to have the strongest feelings and images

associated with them.

For most people, the word mother calls up very strong positive feelings and

associations--loving, self-sacrificing, always there for you, understanding; the denotative

meaning, on the other hand, is simply "a female animal who has borne one or more

chldren." Of course connotative meanings do not necessarily reflect reality; for instance,

if someone said, "His mother is not very motherly," you would immediately understand

the difference between motherly (connotation) and mother(denotation).

Abstract language refers to things that are intangilble, that is, which are perceived not

through the senses but by the mind, such as truth, God, education, vice, transportation,

poetry, war, love. Concrete language identifies things perceived through the senses

(touch, smell, sight, hearing, and taste), such as soft, stench, red, loud, or bitter.

Literal language means exactly what it says; a rose is the physical flower. Figurative

language changes the literal meaning, to make a meaning fresh or clearer, to express

complexity, to capture a physical or sensory effect, or to extend meaning. Figurative

language is also called figures of speech. The most common figures of speech are these:

o A simile: a comparison of two dissimilar things using "like" or "as", e.g., "my

love is like a red, red rose" (Robert Burns).

o A metaphor: a comparison of two dissimilar things which does not use "like" or

"as," e.g., "my love is a red, red rose" (Lilia Melani).

o Personification: treating abstractions or inanimate objects as human, that is,

giving them human attributes, powers, or feelings, e.g., "nature wept" or "the

wind whispered many truths to me."

o hyperbole: exaggeration, often extravagant; it may be used for serious or for

comic effect.

o Apostrophe: a direct address to a person, thing, or abstraction, such as "O

Western Wind," or "Ah, Sorrow, you consume us." Apostrophes are generally

capitalized.

o Onomatopoeia: a word whose sounds seem to duplicate the sounds they

describe--hiss, buzz, bang, murmur, meow, growl.

o Oxymoron: a statement with two parts which seem contradictory; examples: sad

joy, a wise fool, the sound of silence, or Hamlet's saying, "I must be cruel only to

be kind"

Elevated language or elevated style: formal, dignitifed language; it often uses more

elaborate figures of speech. Elevated language is used to give dignity to a hero (note the

speechs of heros like Achilles or Agamemnon in the Iliad), to express the superiority of

God and religious matters generally (as in prayers or in the King James version of the

Bible), to indicate the importance of certain events (the ritual language of the traditional

marriage ceremony), etc. It can also be used to reveal a self-important or a pretentious

character, for humor and/or for satire.

Lyric Poetry: a short poem with one speaker (not necessarily the poet) who expresses thought

and feeling. Though it is sometimes used only for a brief poem about feeling (like the sonnet).it

is more often applied to a poem expressing the complex evolution of thoughts and feeling, such

as the elegy, the dramatic monologue, and the ode. The emotion is or seems personal In classical

Greece, the lyric was a poem written to be sung, accompanied by a lyre. Click here for a

discussion of Reading Lyric Poetry.

Meter: a rhythm of accented and unaccented syllables which are organized into patterns,

called feet. In English poetry, the most common meters are these:

Iambic: a foot consisting of an unaccented and accented syllable. Shakespeare often uses

iambic, for example the beginning of Hamlet's speech (the accented syllables are

italicized), "To be or not to be. Listen for the accents in this line from Marlowe,

"Come live with me and be my love." English seems to fall naturally into iambic patterns,

for it is the most common meter in English.

Trochaic: a foot consisting of an accented and unaccented syllable.

Longfellow's Hiawatha uses this meter, which can quickly become singsong (the

accented syllable is italicized):

"By the shores of GitcheGumee

By the shining Big-Sea-water."

The three witches' speech in Macbeth uses it: "Double, double, toil and trouble."

Anapestic: a foot consisting of two unaccented syllables and an accented syllable. These

lines from Shelley's Cloud are anapestic:

"Like a child from the womb, like a ghost from the tomb

I arise and unbuild it again."

Dactylic: a foot consisting of an accented syllable and two unaccented syllables, as in

these words: swimingly, mannikin, openly.

Spondee: a foot consisting of two accented syllables, as in the word heartbreak. In

English, this foot is used occasionally, for variety or emphasis.

Pyrrhic: a foot consisting of two unaccented syllables, generally used to vary the

rhythm.

A line is named for the number of feet it contains: monometer: one foot, dimeter: two

feet, trimeter: three feet, tetrameter: four feet, pentameter: five feet, hexameter:six

feet, heptameter: seven feet.

The most common metrical lines in English are tetrameter (four feet) and pentameter (five

feet). Shakespeare frequently uses unrhymed iambic pentameter in his plays; the technical name

for this line is blank verse. In this course, I will not be asking you to identify meters and

metrical lines, but I would like you to have some awareness of their existence.

Modern

English poetry is metrical, i.e., it relies on accented and unaccented syllables. Not all poetry

does; Anglo-Saxon poetry relied on a system of alliteration. Skillful poets rarely use one meter

throughout a poem but use these meters in combinations; however, a poem generally has one

dominant meter.

Ode: usually a lyric poem of moderate length, with a serious subject, an elevated style, and an

elaborate stanza pattern.There are various kinds of odes, which we don't have to worry about in

an introductiory course like this. The ode often praises people, the arts of music and poetry,

natural scenes, or abstract concepts. The Romantic poets used the ode to explore both personal or

general problems; they often started with a meditation on something in nature, as did Keats in

"Ode to a Nightingale" or Shelley in"Ode to the West Wind." Click here for a fuller discussion

of the ode.

Paradox: a statement whose two parts seem contradictory yet make sense with more thought.

Christ used paradox in his teaching: "They have ears but hear not." Or in ordinary conversation,

we might use a paradox, "Deep down he's really very shallow." Paradox attracts the reader's or

the listener's attention and gives emphasis.

Point of view: the perspective from which the story is told.

The most obvious point of view is probably first person or "I."

The omniscient narrator knows everything, may reveal the motivations, thoughts and

feelings of the characters, and gives the reader information.

With a limited omniscient narrator, the material is presented from the point of view of

a character, in third person.

The objective point of view presents the action and the characters' speech, without

comment or emotion. The reader has to interpret them and uncover their meaning.

A narrator may be trustworthy or untrustworthy, involved or uninvolved. Click here for an

illustration of these points of view in the story of Sleeping Beauty.

Rhyme:the repetition of similar sounds. In poetry, the most common kind of rhyme is end

rhyme, which occurs at the end of two or mroe lines. Internal rhyme occurs in the middle of a

line, as in these lines from Coleridge, "In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud" or "Whiles all

the night through fog-smoke white" ("The Ancient Mariner"). There are many kinds of end

rhyme:

True rhyme is what most people think of as rhyme; the sounds are nearly identical-notion, motion, potion, for example.

Weak rhyme, also called slant, oblique, approximate, or half rhyme, refers to words

with similar but not identical sounds, e.g., notion-nation, bear-bore, ear-are. Emily

Dickinson frequently uses partial rhymes.

Eye rhyme occurs when words look alike but don't sound alike--e.g., bear-ear.

Sonnet: a lyric poem consisting of fourteen lines. In English, generally the two basic kinds of

sonnets are the Italian or Petrarchan sonnet and the Shakespearean or Elizabethan sonnet. The

Italian/Petrarchan sonnet is named after Petrarch, an Italian Renaissance poet. The Petrarchan

sonnet consists of an octave (eight lines) and a sestet (six lines). The Shakespearean

sonnet consists of three quatrains (four lines each) and a concluding couplet (two lines). The

Petrarian sonnet tends to divide the thought into two parts; the Shakespearean, into four.

Structure: framework of a work of literature; the organization or over-all design of a work. The

structure of a play may fall into logical divisions and also a mechanical division of acts and

scenes. Groups of stories may be set in a larger structure or frame, like The Canterbury

Tales, The Decameron, or The Arabian Tales.

Style: manner of expression; how a speaker or writer says what he says. Notice the difference in

style of the opening paragraphs of Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms and Mark Twain's The

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn:

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and

the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white

in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by

the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The

trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops

marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the

soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

A Farewell to Arms

You don't know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of

Tom Sawyer; but that ain't no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the

truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Symbol: in general terms, anything that stands for something else. Obvious examples are flags,

which symbolize a nation; the cross is a symbol for Christianity; Uncle Sam a symbol for the

United States. In literature, a symbol is expected to have significance. Keats starts his ode with a

real nightingale, but quickly it becomes a symbol, standing for a life of pure, unmixed joy; then

before the end of the poem it becomes only a bird again.

Tone: the writer's attitude toward the material and/or readers. Tone may be playful, formal,

intimate, angry, serious, ironic, outraged, baffled, tender, serene, depressed, etc.

Theme: (1) the abstract concept explored in a literary work; (2) frequently recurring ideas, such

as enjoy-life while-you-can; (3) repetition of a meaningful element in a work, such as references

to sight, vision, and blindness in Oedipus Rex. Sometimes the theme is also called the motif.

Themes in Hamlet include the nature of filial duty and the dilemma of the idealist in a non-ideal

situation. A theme in Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale" is the difficulty of correlating the ideal and

the real.

Tragedy: broadly defined, a literary and particularly a dramatic presentation of serious actions in

which the chief character has a disastrous fate. There are many different kinds and theories of

tragedy, starting with the Greeks and Aristole's definition in The Poetics, "the imitation of an

action that is serious and also, as having magnitude, complete in itself...with incidents arousing

pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its catharsis of such emotions." In the Middle Ages,

tragedy merely depicted a decline from happiness to misery because of some flaw or error of

judgment. Click here for a fuller discussion of tragedy and the tragic vision.

Aesthetic distance: degree of emotional involvement in a work of art. The most obvious

example of aesthetic distance (also referred to simply as distance) occurs with paintings. Some

paintings require us to stand back to see the design of the whole painting; standing close, we see

the technique of the painting, say the brush strokes, but not the whole. Other paintings require us

to stand close to see the whole; their design and any figures become less clear as we move back

from the painting.

Similarly, fiction, drama, and poetry involve the reader emotionally to different degrees.

Emotional distance, or the lack of it, can be seen with children watching a TV program or a

movie; it becomes real for them. Writers like Faulkner, the Bronte sisters, or Faulkner pull the

reader into their work; the reader identifies closely with the characters and is fully involved with

the happenings. Hemingway, on the other hand, maintains a greatr distance from the reader.

Alliteration: the repetition of the same sound at the beginning of a word, such as the repetition

of b sounds in Keats's "beaded bubbles winking at the brim" ("Ode to a Nightingale") or

Coleridge's "Five miles meandering in a mazy motion ("Kubla Khan"). A common use for

alliteration is emphasis. It occurs in everyday speech in such prhases as "tittle-tattle," "bag and

baggage," "bed and board," "primrose path," and "through thick and thin" and in sayings like

"look before you leap."

Some literary critics call the reptition of any sounds alliteration. However, there are

specialized terms for other sound-repetitions. Consonance repeats consonants, but not the

vowels, as in horror-hearer. Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds, please-niece-ski-tree.

See rhyme.

An allusion: a brief reference to a person, event, place, or phrase. The writer assumes will

recognize the reference. For instance, most of us would know the difference between a

mechanic's being as reliable as George Washington or as reliable as Benedict Arnold. Allusions

that are commonplace for readers in one era may require footnotes for readers in a later time.

Ambiguity: (1) a statement which has two or more possible meanings; (2) a statement whose

meaning is unclear. Depending on the circumstances, ambiguity can be negative, leading to

confusion or even disaster (the ambiguous wording of a general's note led to the deadly charge of

the Light Brigade in the Crimean War). On the other hand, writers often use it to achieve special

effects, for instance, to reflect the complexity of an issue or to indicate the difficulty, perhaps the

impossibility, of determining truth.

The title of the country song "Heaven's Just a Sin Away" is deliberately ambiguous; at a

religious level, it means that committing a sin keeps us out of heaven, but at a physical level, it

means that committing a sin (sex) will bring heaven (pleasure). Many of Hamlet's statements to

the King, to Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern, and to other characters are deliberately ambiguous,

to hide his real purpose from them.

Ballad: a relatively short narrative poem, written to be sung, with a simple and dramatic action.

The ballads tell of love, death, the supernatural, or a combination of these. Two characteristics of

the ballad are incremental repetition and the ballad stanza. Incremental repetition repeats one or

more lines with small but significant variations that advance the action. The ballad stanza is four

lines; commonly, the first and third lines contain four feet or accents, the second and fourth lines

contain three feet. Ballads often open abruptly, present brief descriptions, and use concise

dialogue.

The folk ballad is usually anonymous and the presentation impersonal. The literary

ballad deliberately imitates the form and spirit of a folk ballad. The Romantic poets were

attracted to this form, as Longfellow with "The Wreck of the Hesperus," Coleridge with the

"Rime of the Ancient Mariner" (which is longer and more elaborate than the folk balad) and

Keats with "La Belle Dame sans Merci" (which more closely resembles the folk ballad).

Characterization: the way an author presents characters. In direct presentation, a character is

described by the author, the narrator or the other characters. In indirect presentation, a character's

traits are revealed by action and speech.

Characters can be discussed in a number of ways.

The protagonist is the main character, who is not necessarily a hero or a heroine.

The antagonist is the opponent; the antagonist may be society, nature, a person, or an

aspect of the protagonist. The antihero, a recent type, lacks or seems to lack heroic traits.

A persona is a fictional character. Sometimes the term means the mask or alter-ego of

the author; it is often used for first person works and lyric poems, to distinguish the writer

of the work from the character in the work.

Characters may be classified as round (three-dimensional, fully developed) or as flat

(having only a few traits or only enough traits to fulfill their function in the work); as

developing (dynamic) characters or as static characters.

A foil is a secondary character who contrasts with a major character; in Hamlet, Laertes

and Fortinbras, whose fathers have been killed, are foils for Hamlet.

Convention: (1) a rule or practice based upon general consent and upheld by society at large; (2)

an arbitrary rule or practice recognized as valid in any particular art or discipline, such as

literature or art (NED). For example, when we read a comic book, we accept that a light bulb

appearing above the head of a comic book character means the character suddently got an idea.

Literary convention: a practice or device which is accepted as a necessary, useful, or

given feature of a genre, e.g., the proscenium stage (the "picture-frame" stage of most

theaters), a soliloquy, the epithet or boast in the epic (which those of you who took Core

Studies 1 will be familiar with).

Stock character: character types of a genre, e.g., the heroine disguised as a man in

Elizabethan drama, the confidant, the hardboiled detective, the tightlipped sheriff, the girl

next door, the evil hunters in a Tarzan movie, ethnic or racial stereotypes, the cruel

stepmother and Prince Charming in fairy tales.

Stock situation: frequently recurring sequence of action in a genre, e.g., rags-to-riches,

boy-meets-girl, the eternal triangle, the innocent proves himself or herself.

Stock response: a habitual or automatic response based on the reader's beliefs or

feelings, rather than on the work itself. A moralistic person might be shocked by any

sexual scene and condemn a book or movie as dirty; a sentimentalist is automatically

moved by any love story, regardless of the quality of the writing or the acting; someone

requiring excitement may enjoy any violent story or movie, regardless of how mindless,

unmotivated or brutal the violence is.

Fiction: prose narrative based on imagination, usually the novel or the short story.

Genre: a literary species or form, e.g., tragedy, epic, comedy, novel, essay, biography, lyric

poem. Click here for a fuller discussion of genres.

Irony: the discrepancy between what is said and what is meant, what is said and what is done,

what is expected or intended and what happens, what is meant or said and what others

understand. Sometimes irony is classified into types: in situational irony, expectations aroused

by a situation are reversed; in cosmic irony or the irony of fate, misfortune is the result of fate,

chance, or God; in dramatic irony. the audience knows more than the characters in the play, so

that words and action have additional meaning for the audience; Socractic irony is named after

Socrates' teaching method, whereby he assumes ignorance and openness to opposing points of

view which turn out to be (he shows them to be) foolish. Click here for examples of irony.

Irony is often confused with sarcasm and satire:

Sarcasm is one kind of irony; it is praise which is really an insult; sarcasm generally

invovles malice, the desire to put someone down, e.g., "This is my brilliant son, who

failed out of college."

Satire is the exposure of the vices or follies of an indiviudal, a group, an institution, an

idea, a society, etc., usually with a view to correcting it. Satirists frequently use irony.

Language can be classified in a number of ways.

Denotation: the literal meaning of a word; there are no emotions, values, or images

associated with denotative meaning. Scientific and mathematical language carries few, if

any emotional or connotative meanings.

Connotation: the emotions, values, or images associated with a word. The intensity of

emotions or the power of the values and images associated with a word varies. Words

connected with religion, politics, and sex tend to have the strongest feelings and images

associated with them.

For most people, the word mother calls up very strong positive feelings and

associations--loving, self-sacrificing, always there for you, understanding; the denotative

meaning, on the other hand, is simply "a female animal who has borne one or more

chldren." Of course connotative meanings do not necessarily reflect reality; for instance,

if someone said, "His mother is not very motherly," you would immediately understand

the difference between motherly (connotation) and mother(denotation).

Abstract language refers to things that are intangilble, that is, which are perceived not

through the senses but by the mind, such as truth, God, education, vice, transportation,

poetry, war, love. Concrete language identifies things perceived through the senses

(touch, smell, sight, hearing, and taste), such as soft, stench, red, loud, or bitter.

Literal language means exactly what it says; a rose is the physical flower. Figurative

language changes the literal meaning, to make a meaning fresh or clearer, to express

complexity, to capture a physical or sensory effect, or to extend meaning. Figurative

language is also called figures of speech. The most common figures of speech are these:

o A simile: a comparison of two dissimilar things using "like" or "as", e.g., "my

love is like a red, red rose" (Robert Burns).

o A metaphor: a comparison of two dissimilar things which does not use "like" or

"as," e.g., "my love is a red, red rose" (Lilia Melani).

o Personification: treating abstractions or inanimate objects as human, that is,

giving them human attributes, powers, or feelings, e.g., "nature wept" or "the

wind whispered many truths to me."

o hyperbole: exaggeration, often extravagant; it may be used for serious or for

comic effect.

o Apostrophe: a direct address to a person, thing, or abstraction, such as "O

Western Wind," or "Ah, Sorrow, you consume us." Apostrophes are generally

capitalized.

o Onomatopoeia: a word whose sounds seem to duplicate the sounds they

describe--hiss, buzz, bang, murmur, meow, growl.

o

Oxymoron: a statement with two parts which seem contradictory; examples: sad

joy, a wise fool, the sound of silence, or Hamlet's saying, "I must be cruel only to

be kind"

Elevated language or elevated style: formal, dignitifed language; it often uses more

elaborate figures of speech. Elevated language is used to give dignity to a hero (note the

speechs of heros like Achilles or Agamemnon in the Iliad), to express the superiority of

God and religious matters generally (as in prayers or in the King James version of the

Bible), to indicate the importance of certain events (the ritual language of the traditional

marriage ceremony), etc. It can also be used to reveal a self-important or a pretentious

character, for humor and/or for satire.

Lyric Poetry: a short poem with one speaker (not necessarily the poet) who expresses thought

and feeling. Though it is sometimes used only for a brief poem about feeling (like the sonnet).it

is more often applied to a poem expressing the complex evolution of thoughts and feeling, such

as the elegy, the dramatic monologue, and the ode. The emotion is or seems personal In classical

Greece, the lyric was a poem written to be sung, accompanied by a lyre. Click here for a

discussion of Reading Lyric Poetry.

Meter: a rhythm of accented and unaccented syllables which are organized into patterns,

called feet. In English poetry, the most common meters are these:

Iambic: a foot consisting of an unaccented and accented syllable. Shakespeare often uses

iambic, for example the beginning of Hamlet's speech (the accented syllables are

italicized), "To be or not to be. Listen for the accents in this line from Marlowe,

"Come live with me and be my love." English seems to fall naturally into iambic patterns,

for it is the most common meter in English.

Trochaic: a foot consisting of an accented and unaccented syllable.

Longfellow's Hiawatha uses this meter, which can quickly become singsong (the

accented syllable is italicized):

"By the shores of GitcheGumee

By the shining Big-Sea-water."

The three witches' speech in Macbeth uses it: "Double, double, toil and trouble."

Anapestic: a foot consisting of two unaccented syllables and an accented syllable. These

lines from Shelley's Cloud are anapestic:

"Like a child from the womb, like a ghost from the tomb

I arise and unbuild it again."

Dactylic: a foot consisting of an accented syllable and two unaccented syllables, as in

these words: swimingly, mannikin, openly.

Spondee: a foot consisting of two accented syllables, as in the word heartbreak. In

English, this foot is used occasionally, for variety or emphasis.

Pyrrhic: a foot consisting of two unaccented syllables, generally used to vary the

rhythm.

A line is named for the number of feet it contains: monometer: one foot, dimeter: two

feet, trimeter: three feet, tetrameter: four feet, pentameter: five feet, hexameter:six

feet, heptameter: seven feet.

The most common metrical lines in English are tetrameter (four feet) and pentameter (five

feet). Shakespeare frequently uses unrhymed iambic pentameter in his plays; the technical name

for this line is blank verse. In this course, I will not be asking you to identify meters and

metrical lines, but I would like you to have some awareness of their existence.

Modern

English poetry is metrical, i.e., it relies on accented and unaccented syllables. Not all poetry

does; Anglo-Saxon poetry relied on a system of alliteration. Skillful poets rarely use one meter

throughout a poem but use these meters in combinations; however, a poem generally has one

dominant meter.

Ode: usually a lyric poem of moderate length, with a serious subject, an elevated style, and an

elaborate stanza pattern.There are various kinds of odes, which we don't have to worry about in

an introductiory course like this. The ode often praises people, the arts of music and poetry,

natural scenes, or abstract concepts. The Romantic poets used the ode to explore both personal or

general problems; they often started with a meditation on something in nature, as did Keats in

"Ode to a Nightingale" or Shelley in"Ode to the West Wind." Click here for a fuller discussion

of the ode.

Paradox: a statement whose two parts seem contradictory yet make sense with more thought.

Christ used paradox in his teaching: "They have ears but hear not." Or in ordinary conversation,

we might use a paradox, "Deep down he's really very shallow." Paradox attracts the reader's or

the listener's attention and gives emphasis.

Point of view: the perspective from which the story is told.

The most obvious point of view is probably first person or "I."

The omniscient narrator knows everything, may reveal the motivations, thoughts and

feelings of the characters, and gives the reader information.

With a limited omniscient narrator, the material is presented from the point of view of

a character, in third person.

The objective point of view presents the action and the characters' speech, without

comment or emotion. The reader has to interpret them and uncover their meaning.

A narrator may be trustworthy or untrustworthy, involved or uninvolved. Click here for an

illustration of these points of view in the story of Sleeping Beauty.

Rhyme:the repetition of similar sounds. In poetry, the most common kind of rhyme is end

rhyme, which occurs at the end of two or mroe lines. Internal rhyme occurs in the middle of a

line, as in these lines from Coleridge, "In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud" or "Whiles all

the night through fog-smoke white" ("The Ancient Mariner"). There are many kinds of end

rhyme:

True rhyme is what most people think of as rhyme; the sounds are nearly identical-notion, motion, potion, for example.

Weak rhyme, also called slant, oblique, approximate, or half rhyme, refers to words

with similar but not identical sounds, e.g., notion-nation, bear-bore, ear-are. Emily

Dickinson frequently uses partial rhymes.

Eye rhyme occurs when words look alike but don't sound alike--e.g., bear-ear.

Sonnet: a lyric poem consisting of fourteen lines. In English, generally the two basic kinds of

sonnets are the Italian or Petrarchan sonnet and the Shakespearean or Elizabethan sonnet. The

Italian/Petrarchan sonnet is named after Petrarch, an Italian Renaissance poet. The Petrarchan

sonnet consists of an octave (eight lines) and a sestet (six lines). The Shakespearean

sonnet consists of three quatrains (four lines each) and a concluding couplet (two lines). The

Petrarian sonnet tends to divide the thought into two parts; the Shakespearean, into four.

Structure: framework of a work of literature; the organization or over-all design of a work. The

structure of a play may fall into logical divisions and also a mechanical division of acts and

scenes. Groups of stories may be set in a larger structure or frame, like The Canterbury

Tales, The Decameron, or The Arabian Tales.

Style: manner of expression; how a speaker or writer says what he says. Notice the difference in

style of the opening paragraphs of Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms and Mark Twain's The

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn:

In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and

the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white

in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by

the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The

trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops

marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the

soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves.

A Farewell to Arms

You don't know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of

Tom Sawyer; but that ain't no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the

truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Symbol: in general terms, anything that stands for something else. Obvious examples are flags,

which symbolize a nation; the cross is a symbol for Christianity; Uncle Sam a symbol for the

United States. In literature, a symbol is expected to have significance. Keats starts his ode with a

real nightingale, but quickly it becomes a symbol, standing for a life of pure, unmixed joy; then

before the end of the poem it becomes only a bird again.

Tone: the writer's attitude toward the material and/or readers. Tone may be playful, formal,

intimate, angry, serious, ironic, outraged, baffled, tender, serene, depressed, etc.

Theme: (1) the abstract concept explored in a literary work; (2) frequently recurring ideas, such

as enjoy-life while-you-can; (3) repetition of a meaningful element in a work, such as references

to sight, vision, and blindness in Oedipus Rex. Sometimes the theme is also called the motif.

Themes in Hamlet include the nature of filial duty and the dilemma of the idealist in a non-ideal

situation. A theme in Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale" is the difficulty of correlating the ideal and

the real.

Tragedy: broadly defined, a literary and particularly a dramatic presentation of serious actions in

which the chief character has a disastrous fate. There are many different kinds and theories of

tragedy, starting with the Greeks and Aristole's definition in The Poetics, "the imitation of an

action that is serious and also, as having magnitude, complete in itself...with incidents arousing

pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its catharsis of such emotions." In the Middle Ages,

tragedy merely depicted a decline from happiness to misery because of some flaw or error of

judgment. Click here for a fuller discussion of tragedy and the tragic vision.

The Four Basic Elements Of Any Novel

By Nicholas Sparks

Characters , Plots & Plotting

Elements of a novel

It's critical to understand these elements and how they are related.

Plot -- There are many definitions of plot, but plot is essentially the story, or the events that make up

what the book is about. Plot, of course, is defined by conflict, either internal (Coming to terms with

the loss of a spouse, for example) or external, (A stalker is watching through the window), and the best

plots are both original and interesting. Complexity of the plot is a matter of taste, so is the setting

(such as time period).

No matter what other definition is given, the very best plots are defined by readers with the simple

phrase, "I couldn't put the book down." In other words, a great story.

Character Development -- Bringing the characters to life in the reader's mind. They can range from

thumbnail sketches to deep, wordy, highly detailed biographies of each character. It's important to

note that different genres and stories require different types of character development.

Writing Style -- How the novel is written. Is the writing style efficient or complex? Does the author use

an extensive vocabulary or get straight to the point? Are words used appropriately with regard to

meaning, or do they seem written to showcase the "sound" of a sentence? Style should always be

appropriate for the genre or story. An appropriate style adds to the texture of the novel; an

inappropriate style does just the opposite. Literary fiction tends t lean toward complex sentences with

original language. Thrillers tend to use shorter, more efficient sentences, especially as the pace

quickens in the novel.

Of course, basic writing rules always apply. Limit the use of adverbs when describing dialogue ("he said

angrily" should read, "he said"), avoid words that add unnecessary emphasis ("he was a little tired"

should read, "he was tired," or "she was very thirsty," should read "she was thirsty") avoid cliches (like,

"It was a dark and stormy night,") use words appropriately and with their proper meaning, make the

sentences clear and coherent, make them original without seeming to strain for originality. And most

important of all, "show" whenever possible, don't "tell." In other words, don't write, "Max was angry."

Show me his anger instead. ("Staring into the fire, Max balled his hands into fists. Not this, he thought,

anything but this.")

For a further look at Style and Rules of Composition, see The Elements of Style by Strunk and White.

Length -- Just what it says. How long is the book? The length should be appropriate to the genre and be

appropriate to the story. The Notebook, which in its final form was 45,000 words, was originally 80,000

words before I edited it down. Why did I cut so much? Because the story was so simple (only two main

characters and two settings, and the majority of the novel was devoted to only a couple of days) that

the additional words didn't add much; in fact, all they did was slow the story to a crawl. In The Rescue,

I cut 20% from the original draft for the same reason. In A Bend in the Road, I cut 25%. In Stephen King's

book, On Writing, he says his general rule of thumb is to cut 10%. According to what I've heard about

Hemingway, his advice was to take the first fifty pages of your novel and cut them down to five pages.

Sometimes when writing, less is more. (Ignore the use of the cliche, but it's appropriate here.)

In most books on writing that I've read, this final aspect is often overlooked, though I don't know why.

Length is critically important in novels. How many times, for instance, have you read a novel that

seems to go "on and on?" I've read plenty. Too many, in fact.

Books that are too long are the sign of laziness by the writer and also imply an arrogance of sorts, one

that essentially says to the reader, "I'm the author here and I know what I'm doing, and if you don't like

it, then that says more about you than me, and we both know which one of us is smarter." Not so. Who,

after all, would have seen the movie Jurassic Park if the length of the movie was six hours? As much as

dinosaurs are interesting and exciting, enough is enough sometimes. Why are so many books too long

these days? Because being efficient is difficult and often time-consuming. It's a lot harder to capture a

character's personality fully in one, original paragraph, than it is to take a page to do so. But efficiency

is one of the characteristics of quality writing. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times," is a

much stronger opening than taking a paragraph or two to say exactly the same thing.

Likewise with novels or scenes that are too short, and though this doesn't seem to happen as

frequently, it does happen at times. Sometimes, characters scream for more detail about them,

sometimes settings do as well. Sometimes adding "bulk" is important to the overall pacing of a novel. If

too much length is bad, so is a book or scene that's too short.

The prose poem is a type of poetry characterized by its lack of line breaks. Although the prose poem

resembles a short piece of prose, its allegiance to poetry can be seen in the use of rhythms, figures of

speech, rhyme, internal rhyme, assonance (repetition of similar vowel sounds), consonance (repetition of

similar consonant sounds), and images. Early poetry (such as the Iliad and the Odyssey, both written

by Homer approximately 2,800 years ago) lacked conventional line breaks for the simple fact that these

works were not written down for hundreds of years, instead being passed along (and presumably

embellished) in the oral tradition. However, once poetry began to be written down, poets began to

consider line breaks as another important element to the art. With the exception of slight pauses and

inherent rhyme schemes, it is very hard for a listener of poetry to tell where a line actually breaks.

The length of prose poems vary, but usually range from half of a page to three or four pages (those much

longer are often considered experimental prose or poetic prose). Aloysius Bertrand, who first

published Gaspard de la nuit in 1842, is considered by many scholars as the father of the prose poem as a

deliberate form. Despite the recognition given to Bertrand, as well as Maurice de Guerin, who wrote

around 1835, the first deliberate prose poems appeared in France during the 18th Century as writers

turned to prose in reaction to the strict rules of versification by the Academy.

Although dozens of French writers experimented with the prose poem in the 1700s, it was not

until Baudelaire’s work appeared in 1855 that the prose poem gained wide recognition. However, it

was Rimbaud’s book of prose poetry Illuminations, published in 1886, that would stand as his greatest

work, and among the best examples of the prose poem. Additional practitioners of the prose poem (or a

close relative) include Edgar Allen Poe, Max Jacob, James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, Amy Lowell, Gertrude

Stein, and T.S. Eliot.Among contemporary practitioners of the prose poem are: Russell Edson, Robert

Bly,Charles Simic, and Rosmarie Waldrop.

Poets of Interest:

Charles Baudelaire

Russell Edson

N. Scott Momaday

Arthur Rimbaud

Charles Simic

Gertrude Stein

Rosmarie Waldrop

Authors:

Louisa May Alcott: Little Women 1832-1888 Louisa May Alcott (November 29, 1832 – March 6, 1888)

was an American novelist. She is best known for the novel Little Women, set in the Alcott family

home, Orchard House in Concord, Massachusetts and published in 1868. This novel is loosely based on

her childhood experiences with her three sisters.

Maya Angelou: I Know Why the caged bird sings Angelou's use of fiction-writing techniques such as

dialogue, characterization, and development of theme, setting, plot, and language has often resulted in

the placement of her books into the genre of autobiographical fiction, but Angelou has characterized them

as autobiographies.

Ray Bradbury ay Douglas Bradbury (born August 22, 1920) is an

American mainstream, fantasy, horror, science fiction, and mystery writer.

Best known for his dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, Bradbury is widely

considered one of the greatest and most popular American writers ofspeculative fiction of the twentieth

century.

Ray Bradbury's popularity has been increased by more than 20 television shows and films using his

writings (see Adaptations of his work).

Main article: List of works by Ray Bradbury

Although he is often described as a science fiction writer, Bradbury does not box himself into a particular

narrative categorization:

First of all, I don't write science fiction. I've only done one science fiction book and that's Fahrenheit 451, based on

reality. Science fiction is a depiction of the real. Fantasy is a depiction of the unreal. So Martian Chronicles is not

science fiction, it's fantasy. It couldn't happen, you see? That's the reason it's going to be around a long time—

because it's a Greek myth, and myths have staying power.[9]

On another occasion, Bradbury observed that the novel touches on the alienation of people by media:

In writing the short novel Fahrenheit 451 I thought I was describing a world that might evolve in four or five decades.

But only a few weeks ago, in Beverly Hills one night, a husband and wife passed me, walking their dog. I stood

staring after them, absolutely stunned. The woman held in one hand a small cigarette-package-sized radio, its

antenna quivering. From this sprang tiny copper wires which ended in a dainty cone plugged into her right ear. There

she was, oblivious to man and dog, listening to far winds and whispers and soap-opera cries, sleep-walking, helped

up and down curbs by a husband who might just as well not have been there. This was not fiction. [10]

Besides his fiction work, Bradbury has written many short essays on the arts and culture, attracting the

attention of critics in this field. Bradbury was a consultant for the American Pavilion at the 1964 New York

World's Fair and the original exhibit housed in Epcot's Spaceship Earth geosphere at Walt Disney

World [11][12][13].

Bradbury was a close friend of Charles Addams and collaborated with him on the creation of the macabre

"Family" enjoyed by New Yorker readers for many years and later popularized as The Addams Family.

Bradbury called them the Elliotts and placed them in rural Illinois. His first story about them was

"Homecoming," published in the New Yorker Halloween issue for 1946, with Addams illustrations. He and

Addams planned a larger collaborative work that would tell the family's complete history, but it never

materialized and according to a 2001 interview they went their separate ways. [14] In October 2001,

Bradbury published all the Family stories he had written in one book with a connecting narrative, From the

Dust Returned, featuring a wraparound Addams cover.[15]

In 1953, Bradbury published perhaps his most famous work, Fahrenheit 451, a powerfully

gripping tale of a futuristic society that outlaws the possession of books. Montag, a fireman and

hero of the story, undergoes a complete character transformation, finally joining a group of

nomads who commit classic literature to memory.

Stephan Crane Stephen Crane (November 1, 1871 – June 5, 1900) was an American novelist, short

story writer, poet and journalist. Prolific throughout his short life, he wrote notable works in

theRealist tradition as well as early examples of American Naturalism and Impressionism. He is

recognized by modern critics as one of the most innovative writers of his generation.

The eighth surviving child of highly devout parents, Crane was raised in several New Jersey towns

and Port Jervis, New York. He began writing at the age of 4 and had published several articles by the age

of 16. Having little interest in university studies, he left school in 1891 and began work as a reporter and

writer. Crane's first novel was the 1893 Bowerytale Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, which critics generally

consider the first work of American literary Naturalism. He won international acclaim for his 1895 Civil

War novel The Red Badge of Courage, which he wrote without any battle experience.

In 1896, Crane endured a highly publicized scandal after acting as a witness for a suspected prostitute.

Late that year he accepted an offer to cover the Spanish-American War as awar correspondent. As he

waited in Jacksonville, Florida for passage to Cuba, he met Cora Taylor, the madam of a brothel with

whom he would have a lasting relationship. While en route to Cuba, Crane's ship sank off the coast of

Florida, leaving him marooned for several days in a small dinghy. His ordeal was later described in his

well-known short story, "The Open Boat". During the final years of his life, he covered conflicts

in Greece and Cuba, and lived in England with Cora, where he befriended writers such as Joseph

Conrad and H. G. Wells. Plagued by financial difficulties and ill health, Crane died of tuberculosis in

a Black Forest sanatorium at the age of 28.

At the time of his death, Crane had become an important figure in American literature. He was nearly

forgotten, however, until two decades later when critics revived interest in his life and work. Stylistically,

Crane's writing is characterized by descriptive vividness and intensity, as well as

distinctive dialects and irony. Common themes involve fear, spiritual crisis and social isolation. Although

recognized primarily for The Red Badge of Courage, which has become an American classic, Crane is

also known for his unconventional poetry and heralded for short stories such as "The Open Boat", "The

Blue Hotel", "The Monster" and "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky". His writing made a deep impression on

20th century writers, most prominent among them Ernest Hemingway, and is thought to have inspired

the Modernists and the Imagists.

rane's work is often thematically driven by Naturalistic and Realistic concerns, including ideals versus

realities, spiritual crises and fear. These themes are particularly evident in Crane's first three

novels, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, The Red Badge of Courage and George's Mother.[171] The three

main characters search for a way to make their dreams come true, but ultimately suffer from crises of

identity.[172] In The Red Badge of Courage, the main character both longs for the heroics of battle but

ultimately fears it, demonstrating the dichotomy of courage and cowardice. He experiences the threat of

death, misery and a loss of self.[173]

Extreme isolation from society and community is also apparent in Crane's work. During the most intense

battle scenes in The Red Badge of Courage, for example, the story's focus is predominately "on the inner

responses of a self unaware of others".[174] In "The Open Boat", "An Experiment in Misery" and other short

stories, Crane uses experiments with light, motion and color to express different degrees of