Christie_Law_140_-_Torts_Winter_2012_Rebecca_Stanley

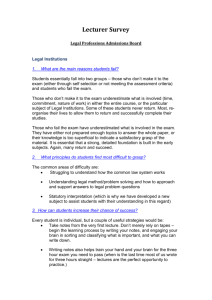

advertisement