Winery Districts v7

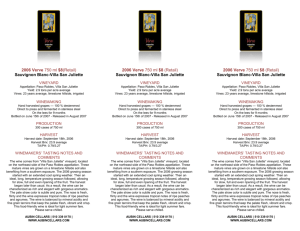

advertisement