Doryanthes NOVEMBER 2011

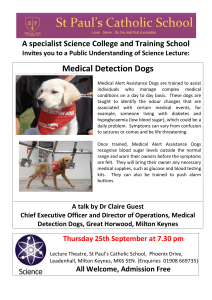

advertisement