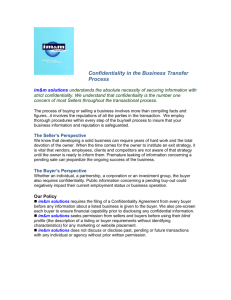

The value of business relationships

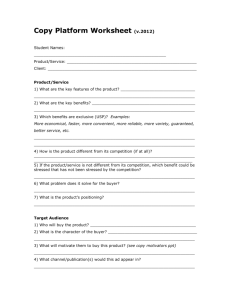

advertisement