Notes on the Money Market and LM Curve – Eco 3202 – Fall 2001

advertisement

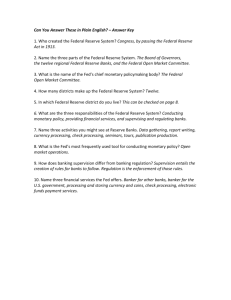

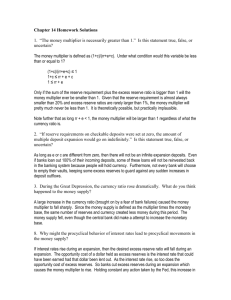

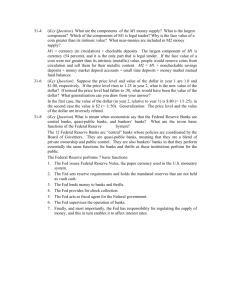

Notes on the Reserve and Money Market – Econ 351 – Fall 2005 Here are some notes to help you along. Our objective is to understand both sides of the money market – money supply where the Fed plays a major role and money demand. We begin with a world with two assets – money and bonds. More generally, we want to define money as a non-interest bearing asset that is used for transactions (transactions money). Bonds on the other hand are less liquid, interest bearing, and cannot be used directly for transactional purposes. Jumping forward, these points are important in determining money demand – for example, if interest rates are very high, then you will hold more bonds since it is so costly to hold money. Naturally, low interest rates mean that the costs of holding money are low so you tend to hold more money (think of Japan). These are important issues in terms of money demand – but we will do money supply first. Money Supply When we think of money supply, we think of the Fed: Doesn’t the Fed control the money supply?? Sort of – let’s be precise and say that the Fed has a lot of influence over the money supply – in particular, M1, which is the monetary aggregate that includes the most liquid assets: Cash (Currency) and Demand Deposits (Checking accounts). M1 also includes travelers’ checks but these are so small in proportion – we’ll just assume them away! There are many other monetary aggregates like M2, M3, LM3, etc. M2 is simply broader than M1 in that M2 includes M1 plus other, less liquid assets like small time savings accounts including CDs. The Federal Reserve, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, used to target M1 since they felt that there was a close connection between M1 and their ultimate objectives. In the early 1980s, this relationship broke down so the Fed targeted M2. This relationship broke down as well and the Fed threw up their hands and follow an eclectic or ‘informational variable’ approach; looking at a variety of variables in hopes of determining the direction of the economy – remember – the Fed most definitely needs to be forward looking. M3 is broader yet and according to a research paper by Chuderewicz, is the best long term predictor of GDP (actually, its real M2)! Back to M1 – for ease of notation well just use M The purpose of the few equations below is for you to understand that the Fed has imperfect control of the money supply due to changes in household and bank behavior that influence the money multiplier and in turn, influences the money supply. We will use the great depression as an example to drive home this point. We will also mention Y2K in this context. 1 Money Supply Define money as above: 1) M = C + D where C = currency (cash) and D = demand deposits (checking accounts) The Fed has pretty darn good control over what is referred to as the monetary base (MB) (also referred to as high powered money since changes in MB due to open market operations result in high powered effects, via the money multiplier, on the money supply). Define MB as follows with C = currency as before, TR equals total reserves, a combination of required reserves (RR) and excess reserves (ER). 2) MB = C + TR Divide 1) by 2) 3) M/MB = (C + D)/(C + TR) Now a trick – divide the numerator and denominator of the RHS (right hand side) of 3) by D. 4) M/MB = (C /D+ D/D)/(C/D + TR/D) Let’s do a few things to 4) – a) get MB on RHS, b) D/D = 1, and c) TR = RR + ER 5) M = [(C /D+ 1)/(C/D + RR/D + ER/D)] MB The term in brackets is referred to as the money multiplier, which is a little different that what you saw in principles. Equation 5) implies that the money multiplier is influenced by household behavior via C/D, which is determined by us. C/D is simply the currency to deposit ratio. For example, if you typically carry $100 in cash and you have $1000 in a demand deposit, then your C/D is 0.1. Think about what happened to C/D during Y2K. Equation 5) also implies that bank behavior influences the money multiplier via ER/D. Even though banks tend to get rid of excess reserves (ER) since they earn no interest, sometimes they hold on to them. What do you think banks were doing during Y2K? Probably holding a lot of ER to meet the liquidity needs of their customers! The last player that can influence the money multiplier is the Fed themselves via RR/D which is simply the reserve requirement ratio (this is what you were supposed to learn in principles). Specifics on the money multiplier: If C/D, ER/D, or RR/D go up, then the multiplier falls. This is important, because if MB remains constant, the money supply will fall along with it. We will now use an example that is a simplified version of what happened during the great depression. 2 Some numbers (totally made up): let C/D = .2 , RR/D = .1 and ER/D = 0 Multiplier = (.2 +1)/ (.2 + .1 + 0) = 4 What does this mean? A couple things; suppose the MB is $ 100 billion and therefore, M = $ 400 billion (given a money multiplier of 4). A 10 billion dollar open market purchase will result in a $40 billion increase in the money supply (remember high powered money!) See the two graphs below. Rs Rs’ i i 100 110 Ms Ms’ 400 440 R (MB) M 3 Question: In the top diagram, the reserve market, what is the interest rate that belongs on the vertical axis? What about the bottom diagram?? The Great Depression – an Example The Fed is blamed by some for causing the great depression or at least failing to respond appropriately. What will a bank run do to C/D ratios? So C/D rose dramatically as people were trying to get their cash. Remember, no FDIC insurance back then. ER/D also rose for two reasons – one, banks were keeping ER to meet the liquidity needs of their customers and two, had no one to lend to; banks were reluctant to make loans in such a dismal environment. Ironically, RR/D went up as well. The Fed was young, less than 20 years in existence and felt that raising the required reserve ratio would make banks more sound as well as giving the public more confidence so that they would not run on banks – in hindsight, raising the required reserve ratio was a mistake! All three components of money multiplier rose during the great depression – impact on money multiplier? Recall Money Multiplier equals: [(C /D+ 1)/(C/D + RR/D + ER/D)] Initially, let C/D = .2 , RR/D = .1 , and ER/D = 0 With numbers: [(.2+ 1)/(.2 + .1 + 0)] = 4 Now account for changes in C/D, RR/D, ER/D Let C/D up to .5, RR/D up to .2, ER/D up to .3 [(.5+ 1)/(.5 + .2 + .3] = 1.5 NEW Multiplier = 1.5 With numbers – before the great depression M = ( 4 ) MB 4 If MB = $ 100 billion ; M = $ 400 billion Now great depression hits and the multiplier falls to 1.5 MB still at $100 billion ; M = 150 billion Now the Fed isn’t blind – they buy $ 100 billion in Gov Securities (totally made up numbers again), increasing the MB by $100 billion; Money Supply up to $300 billion (1.5 times $200 billion) – still a 25% drop from where it was initially (before great depression). So the Fed pumped up the Monetary Base via open market purchases but it was not enough to offset the dramatic fall in the money multiplier – they should have been easier (should have conducted more open market purchases). The lesson here is that the Fed has incomplete control over the money supply and in order to have better control, they better try to figure out what determines C/D and ER/D ratios. In normal times, these are pretty stable so that ‘normally’, the Fed has pretty good control over the money supply (M1). In terms of graphs – in the reserve market, reserve supply doubled to $200 billion but in the money market, Ms shifted to the left! A few comments: We have FDIC insurance now so bank runs are unlikely. The closest thing to a bank run was the environment during Y2K. People didn’t trust computers and grabbed cash instead. This was foreseeable, so the Fed, to offset the fall in the multiplier, should buy lots of bonds thereby injecting lots of reserves into the system. Did they? Not exactly – they used the discount window instead. They essentially told banks that you can borrow all you need from us, the Fed, without worrying about the standard implicit cost from borrowing from the Fed. Normally, banks are unwilling to borrow from the Fed since borrowing from the Fed sends up a ‘red flag’ and increases the probability of being audited by the Fed, something a bank certainly avoids. As a result, banks normally would rather borrow off of other banks via the federal funds market. But during Y2k they accepted the Feds offer and Y2k was not a problem! The three tools of the Fed 1) Open Market operations, – the buying and selling of government securities, 2) changes in the reserve requirement ratio, 3) Changes in the discount rate. The Fed conducts open market operations every business day – they guess where reserve demand is and supply the necessary reserves in hopes of hitting their Federal Funds Rates target! Sometimes they are wrong – recall this picture? When the federal funds rate is high, then the Fed underestimated reserve demand – that is, reserve demand was higher 5 than they thought it would be. Conversely, if the federal funds rate is lower than target, they overestimated reserve demand. The Fed guesses what reserve demand will be every business day, and conducts the appropriate amount of open market operations in hopes of hitting the FF target as set by the FOMC. Federal Funds Rate 7.5 7.0 6.5 6.0 5.5 5.0 4.5 4.0 J F MA MJ J A S O N D J F MA MJ J A S O N D J 1997 1998 Summary The Fed tries to hit the target for the Federal Funds rate every business day by conducting open market operations – the buying and selling of Government Securities. This target is in accordance with the Fed’s ultimate objectives (remember those!). During 2001 the Fed has pumped up the money supply big time by buying many Government securities. The Fed does not have complete control over the money supply but they do have a lot of influence. 6 Money Demand The other half of the money market - money demand There are two main determinants of money demand First – real income – if your real income goes up you will live a better life and in order to live a better life you consume more and in order to consume more you need to hold more money. Graphically, an increase in real income shifts the money demand curve to the right. Second – the cost of holding money is the interest rate – the higher the interest rate, the higher the cost of holding money so the less money you will hold. This idea gives us a negatively sloped money demand as shown below. i 6 A B 4 Md (Y,PS) 400 440 M A simple description: When rates are 6 percent, people hold 400 in money balances – quite costly to hold money. An extreme case may help bring the point home – suppose for a second that rates are 100% - how much money would you hold? A meals worth? Now suppose rates are zero, how much money would you hold? Get the picture? The variables in parentheses are shift variables – as noted before, a higher real income means more transactions and more transactions require people to hold more money. The PS term is included and stands for portfolio shocks – think again about Y2K. People wanted to hold more money, not because of a change in interest rates nor a change in real income, they just wanted to readjust their portfolios due to Y2K. This would be depicted as a rightward shift in money demand and is referred to as a portfolio shock! 7 Combining money supply and money demand We are now ready to combine money supply and money demand. For the following analysis we will assume that the money multiplier is stable and therefore, restrict shifts in the money supply curve to open market operations only. Recall that money demand shifts when real income rises or falls, and for the time being we’ll ignore portfolio shocks (PS). 8