Threshold

The Process of the Vision Fast: A (Trans)Personal Journey

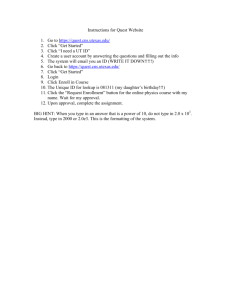

This paper will explore the author’s personal and symbolic journey while under going training as a vision fast facilitator at the ‘School of Lost Borders’ in Death Valley

California. It will act as a phenomenological account of the experience drawing from what Ferrer (2002) has argued; that spiritual knowing is a participatory process, a co-creation that moves beyond subject and object, knowing and being, epistemology and ontology, proposing that spiritual knowing is enactive and is transformative

(Ferrer 2005 P109). The stages of the fast: Severance, Threshold and Incorporation, will be explored in relation to my personal experience. Finally I will examine the transpersonal aspects of the experience in relation to their transformative potential and the concept of the ‘Hero’s Journey’(Campbell 1949)

The history of the vision fast/quest (I will use these terms interchangeably) finds its origins in a variety sources. The term was taken from Native American tradition, although this type of activity has historically been part of many indigenous cultures around the world. The term has evoked some controversy from Native Americans so in the United States the term is being used less and less by wilderness trip leaders

(Segal 2005).

It is not my intention to give an exhaustive summary of its history, but only to map out the territory and form of the fast. The process of the fast can be seen as a

‘container’ rooted in mythological, historical and psycho-spiritual contexts. It is a profoundly physical experience which gives rise to both subtle and concrete dimensions of reality, which in turn mirror aspects of the intra and inter psychic world of the faster. The experience is then magnified by the inter-relationship with nature.

I intend to explore the form of the fast which involves the three stages of severance, threshold and incorporation. This form gives birth to the creation of the faster’s own

‘mono-myth’: their own heroic journey. I will discuss this in relation to Campbell’s seminal work ‘The Hero with A Thousand Faces’ (Campbell 1949). I also want to talk about my own personal process during and perhaps most importantly, after the fast experience. How, for me, the bringing back of the gift, what Black elk describes ‘As the vision on earth for the people to see’(Black Elk 1972) constituted a ‘dark night of the soul’ (Grof and Grof 1991). I will then explore the different transpersonal aspects of the quest process, examining the transformative potential of this experience.

Van Gennep (1960) defined the dynamics of the wilderness fast or rites of passage following a three phase formula: severance (‘separation’), threshold (‘marge’), and incorporation (agregation’). Campbell (1949) proposes that the rights of initiation , teach the lesson of the essential oneness of the individual and the universe. He also views the ceremonial as submission to the inevitability of destiny. We are one and the same with the group and with the universe we cannot control fate, according to

Campbell, the aim of the journey is not to ‘see’ but to realise one ‘is’.

The modern day hero quester creating his/her own monomyth through the ritual and ceremony of the fast comes back to a society devoid of meaningful symbols and rituals to celebrate his/her process, to verify his new life status and to mark the transition or crisis that he/she has been through. It is precisely this loss of ritual and

meaningful ways to mark transitions that the use of rites of passage ceremonies is seeking to reinstate.

I will next explore the container of the quest - the stages that the quester must go through in order to undergo the rite of passage in a way that will keep them psychologically, spiritually and physically safe.

“The vision quest, fasting quest, and all other wilderness rights of passage are but circles drawn in the dust, empty forms to be filled with the unique values and perceptions of the participants, mirrors in which they themselves are reflected” (P24

Foster and Little 1989)

Severance

This is the time for working on one’s intent to fast, in preparation for participation in the rite of the vision quest. This clarification of intent to fast is an important part of the process. Davis (2003) proposes that traditionally much of a person’s life education provided her or him with the practical and spiritual tools for a vision quest. For the modern day quester this process can take up to a year, from first stating their desire to fast to actually partaking in the vision quest.

The mono-mythic journey starts at the end and ends with the beginning, the rebirth.

The severance stage is imbued not only with metaphors and rituals that focus on intent to fast, but to mark endings and to think about transitions; what is being left behind?

What will one be seeking to mark in this life transition? If the quest is part of overcoming a crisis, what will it take to face the dragon? What rituals will need to be enacted at this stage in order to focus one’s intent to understood fully why the fast is being undertaken. All around at this stage are the metaphors of death. What will need to die? What will die within me in order that I can pass through one life stage to the next?

This phase is marked by separation: the hero quester, must be prepared to leave behind that which is familiar and go into a wilderness place cut off from the comforts of electric lighting, heating, removed from the rituals of food and eating and the daily routines of life.

One of the ways of preparing and working on intent is to go on the day or medicine walk. This is to walk from dawn until dusk within a natural place and to fast during this process. This can be seen as a miniature version of the 3-4 day fast to come and will hopefully be rich with metaphors of the bigger personal meaning of the fast. It is a process that helps one hone the intent for the fast, to clarify what is it that they are marking in this transition?

The starting point for my day walk was Beachy Head the symbolic importance of which, in terms of ending at the beginning, only really became fully apparent to me in writing this paper. For those that do not know this Sussex beauty spot, it is part of the

Seven Sisters country park. The beautiful chalk cliffs that traverse this part of the south coast are a notorious suicide spot, it is a place where people go to end their life.

At the time this wasn’t a conscious decision on my part, merely a geographical practicality, somewhere in nature where I could do a circular walk. I can now see that

it was a powerful image of where I was to end up as part of my struggle to incorporate after the fast. In the dark depressive days that befell me as part of my year of incorporation, suicide and suicidal ideation became a close companion.

During the walk I encountered life, death and vulnerability in the form of two baby birds left abandoned by their mother, one already dead, the other looking lost and confused. I pondered whether to stop and help the bird but was unable to really envision what I could do to save it. I walked on hoping its mother would find it or that nature would take its course swiftly. The birds seemed to be speaking to me of the life and death in myself, and how something had to die in order for me to face my vulnerabilities. At this stage I was unsure of its overall meaning in my life and how eventually facing these issues in terms of my own vulnerabilities and helplessness, would save my life.

Other rituals of severance include the death lodge, where participants are encouraged to view their lives, not in a critical, analytical or psychological sense, but literally as a dying person would look back on their life, celebrating the positive and negative events that have given shape to their character. Another exercise is the night walk: to walk alone at night in a natural place encountering the creatures and habitats without the aid of sunlight. This is a good way of allowing the participant to acknowledge some of their fears (literal and metaphorical) of the dark, in the external environment and within themselves and to experience that they are survivable.

After participating in a variety of rituals and exercises I came to the conclusion that my intent was to mark my transition to adulthood, and to have adult relationships. For a long period in my late twenties and early thirties I felt I had been running away from intimacy, from my own fear of commitment, and the risk and the pain that this involved. The fast I believed, would enable me to mark this transition and allow adult relationships to happen in my life.

Threshold

“With the personification of his destiny to guide and aid him, the hero goes forward in his adventure until he comes to the ‘threshold guardian’ at the entrance to the zone of magnified power” (P77 Campbell 1949)

The threshold guardian for the modern quester normally consists of the persons own fear. Fear of the unknown, the fear of not eating for four days, the fear of being alone in the darkness, fear of the power of nature in the wilderness place. Beyond the fear/threshold guardian lies the unknown: darkness and danger, the myriad projections of the quester’s conscious and unconscious fears and terrors. These fears must be faced as the quester moves into the threshold time. This is one of the therapeutic aspects of the fast process, that a fear faced and overcome, terror that can be sat with and looked into, becomes part of the monomyth. The sense of achievement and bravery involved in participating in this process should not be underestimated.

Compared to the months and even years taken in traditional therapy in order to achieve a sense of self esteem and personal power, the quest can act as a very

powerful mobilizer of fear and then a containing space in which the person can find their own sense of themselves. Rituals and exercises performed during the process can act as a way of managing the issues that arise and hold a potentially transformative power for the person engaging and marking a transition in their life.

Recent research quoted by James (2005) showed that the ‘wilderness’ is strongly associated with both death and uncontrollability and that in order to feel the beauty we have to manage these fears. The research showed that people who had an active attitude to manage their fears were better at enjoying the wilderness.

Threshold begins with a death, a severance (Foster and Little 1992). This part of the creation of the monomyth in the hero’s journey comprises of the real ordeal/adventure for the hero. The stage is full of potentially healing emotional states, with the exposure, alone to the elements and to the experience of fasting in a wilderness place.

The nature of subtle reality that one potentially encounters during the quest process can be looked at in a number of ways, I will explore these later in looking at the transpersonal aspects of the quest/fast process. The ways in which we can understand the manifold nature of the communication we receive in the wilderness context depends on the personal sense-making structure of the faster, the religious, spiritual symbolic belief systems that they hold and will use in order to help them process the quest experience.

I attempted to make sense of my encounters in nature, in terms of metaphorical communication. This is where the person is guided by intent and makes some attempt to move into a threshold space, achieved by being ‘open ‘ and looking for the nature of the symbolic/metaphorical communication that can be present. This communication, at once both deeply personal but containing elements of bigger mythic journey undertaken by other hero and heroines, can be used by the participant to create a coherent narrative of the experience, one that can be shared with the wider community of fasters and other interested parties.

Segal’s (2005) research exploring phenomenological accounts of wilderness experiences sees recurring themes of trees and animals that appear to mirror human life. She goes onto to say that the essence of ecopsychology as a holistic clinical practice lies in the acknowledging the importance of meaningful personal relationship with the natural world. This relationship has been argued by ecopsychologists to be damaged: it is indisputable that we are in the middle of an ecological crisis and a psychological crisis and the two are deeply related.

The idea of nature as a mirror and a healer is one that has been posited by other ecopsychologists. Contact with nature is essential for our mental and emotional wellbeing (Burns 1998, Rozack 1992, Davies 2003), the idea that all environments

‘mirror’ back to us aspects of ourselves – reinforcing certain qualities attitudes and self concepts. Davies (2003) proposes that familiar environments mirror familiar feelings, roles and identities, while the more unfamiliar the environment the greater the potential for change. Within a shamanic tradition the fast represents communication with the animate form of the spirit world represented in nature. The relationship between humans and nature and between matter and spirit, so central to shamanism, can be experienced in the quest process within a wilderness place.

Indeed, it may even be found that plants and animals are directly communicating to the faster. For the shaman, a healer ‘par extraordinaire’, the patient’s emotions are attached to transactional symbols which are illustrated through the shared creation of myth making structures. In this way shamanism is not dissimilar to psychotherapy, with the experience generated by culturally specific symbols made sense of within shared cultural myth (Dow 1986). In the same way the faster can enact rituals of transformation in the natural world, by manipulating and interpreting and therefore generating meaning from symbols found in nature to effect emotional transition.

If the fool would persist in his folly, he would become wise. (William Blake)

As I walked out from base camp on the 5 th August 1999 to the place where I had chosen to fast, the voice of doubt echoed in my ears: Why am I doing this? Is any of this real? What does it mean? As I walked I talked to that side of myself “I think you will always be there questioning, doubting the rituals, undermining the value of the process”. In the subsequent years I have learnt to make friends with this voice, taking from what Pema Chodron (Chodron 2001) states, that the emotions we have right now are the emotions we need and any wisdom that exists, exists in what we already have. Our wisdom is all mixed up with our neurosis, our brilliance mixed up with our confusion and therefore it doesn’t do any good to get rid of our negative aspects, because in that process we get rid of our basic wonderfulness.

You could say I felt wonderfully doubtful when I walked out to my fasting spot. It was at the bottom of a steepish hill on a flat ledge overlooking a valley of rock dust and sand typically of the geography of Death Valley. The was a flat rock about three foot by three foot which made a natural table on which to set up my altar. There were some pineon pine and a juniper tree from which to tie my tarpalin cover, under which

I would be sleeping and resting from the shade of the intense sun. Beyond the brief plateau the drop continued with tumbling scree to the valley floor. I hoped the vista would sustain me through the four days and nights of the fast.

On each day I chose to walk in a particular direction. The Four Shields psychology, developed by Steven Foster and Meredith Little (Foster and Little 1998) of which I will now say a little, gave form to the particular direction I was walking. Based on the

Native American tradition of the ‘medicine wheel’, the four directions correspond with the four points of the compass and the four seasons. They also represent aspects of our psychological make up and the stages of maturity that the quester is seeking to pass through in the rite of passage. The four shields has a kinship with ancient psychology where there was no differentiation between people and nature, where human life was intimately tied into the seasonal changes.

South is summer, the psychological aspect is of childhood and bodily sensation, instinct, urge, desire and lust. During the fast process, the faster may feel the physicality of summer in the connection with their body, their joy and their playfulness. West is autumn, the psychological aspect is of adolescence, introspection, emotions such as fear and self doubt may be present in this shield. It is a place of initiation when the child of summer is preparing to become the adult of winter. You can see the doubt of the west very much in my story (perhaps even over represented).

The North is winter, the psychological aspect is of adulthood, of mind, design and

order. The adult of winter must do what needs to be done in order to survive, to store food for the long dark nights of winter, to make sure there is enough fuel for warmth.

It is the ability of the faster to look after themselves, to put up the tarp, to stay out of the sun, to drink enough water, to know when the fast is over, even before the time and to be adult enough to return in order to look after oneself. The adult is also present in the buddy system of the fast when one faster pairs up with another and communicates with a stone pile in order to let the other know she or he is O.K. It is this adult who would raise the alarm and return to base camp if anything was amiss.

Finally the adult makes the transition to the East, which is spring, the psychological state is a reflection of the other shields manifest in wisdom and the position of ‘elder’ but paradoxically of infant and rebirth. It is the state of insight, spirituality, healing.

On day one I walked to the south further along the valley then traversing up the side of a slope I came to an area of vegetation, where a dry bush had been burnt in a fire.

From the ashes new growth was emerging looking much healthier than before. With more nutrients from the ashes that were sustaining new growth. I took from this encounter a metaphor of my difficult childhood: growing up in a barren environment, the product of an unhappy marriage, an experience that had ‘burnt’ me, in a similar way to the bushes being burnt. My interest in psychology and therapy was largely a result and an attempt, as I suspect of all therapists, to heal myself. I wondered whether

I had to feel pain again to grow, to heal, to seek nutrients from the ashes of my experience. It was an omen of my future incorporation.

On day two I planned to walk to the west, as I was readying to go a group of about forty Jack Dawes flew overhead heading west which I took to be confirmation of my route. As I started to head to the west, the path took me down into the Canyon. The voice of Gigi Coyle one of the leaders of the fast echoed in my head: ‘don’t go down into the canyon its not safe’. Indeed, the steep scree ridden slopes magnify the danger of slipping or falling. It was an adolescent thing to do to ignore the advice of an elder and go ahead regardless. About halfway down the side of the canyon, the north shield of my adult spoke and reminded me of the promise I had made to the group before I went out: to keep safe. A rock appeared to my left and I decided to sit and contemplate my west shield here and think about my self doubt. I was visited by another group of beautiful blue birds chattering away. I sat and marvelled at the beauty of the spot and any west thoughts of introspection and darkness dissipated as I enjoyed the vista.

At night during the fast I would have vivid dreams and wake and write them in my journal. By the second day the effects of not eating were beginning to hit home: I had slight cramps in my stomach and would take gulps of water to keep the hunger pangs at bay. By the third day I had some diarrhoea as the toxins in my body washed through my system. Over all I felt pretty good. By the end of the third day I found myself fantasising about food, in particular a vegetable korma, garlic naan, onion bhajis, washed down with an ice cold lager. Although at times thinking about food would make me feel nauseous.

A reminder to my adult self and the North came when I visited my buddy spot, a place where you communicated with a pre chosen partner who was also fasting nearby to let him/her know you were O.K On the first day I merely shifted some stones around in my pile to let him know I was O.K. But when I returned he had created ornate and

beautiful patterns of different coloured stones, which touched me with their clever arrangements and thoughtfulness. Self disgust crept in: typical of myself, I thought, to not value the relationship fully. Look what time and care he takes over this, whilst you just sling a few stone down. It was another powerful symbolic communication to me about the way I was conducting my relationships and linked to my intent. I said to myself “you need to take more effort and care in your relationships, it is important in marking your transition to adulthood and having ‘adult’ relationships”.

I crushed an ant by mistake whilst resting one afternoon, I sat and was absorbed with morbid thoughts around that accidental death. I wept uncontrollable tears of grief, for myself and my certain death, the deaths of those close to me and the death of my father six years previously from cancer. As I was weeping and managing to bring the feelings of grief under control after an hour of crying, I noticed other ants come to carry the dead ant off. Death is all part of the process a voice inside me said.

Day four was all about the East and attaining wisdom and marking the transition of my fast. The theme of death was also strongly around. I thought that I would just mark my last day by visiting my buddy pile and honouring that relationship and sit and pray and think about death and rebirth and my purpose in coming back.

Contemplating who and what I will invite into my purpose circle which I will sit in tonight trying to keep awake and meditating and praying for the gifts I will bring back to my people.

As I sat I was distracted by irritations, the ants crawling around me, people who annoyed me back home and at work, the irritation started to build into anger and I was consumed with rage, at the ants, people and myself for not being able to sit and be wise. ‘Fuck them all’ I raged at the canyon and threw rocks and stones in an attempt to dissipate my rage, eventually it subsided and I calmed down and was able to sit.

That night I struggled to stay awake in my purpose circle I invited in people whom I wanted to be with me, people who I wanted to say sorry to, mainly past girlfriends for my inability to commit. It would all now be different: I would now have adult relationships I would be an adult, I forgot the words of Gigi Coyle: ‘don’t put an outcome on the ritual that things will be different’.

The dawn took a long time to rise, but when it broke I was gripped by a fear for my return that I wouldn’t remember all the things I had learnt and that I wouldn’t bring much back. But I felt damn good, I had done the quest, survived four days and nights in desert without food, praying for my vision. I was looking forward to my return.

Incorporation

Steven Foster asks in the ‘Book of the Vision Quest’: are you prepared to face the consequences you bring back from the sacred mountain? You too will find that if you do not use the treasures you discover you will die a living death. It is dangerous to ask for gramercy from god and do nothing with it. A stark warning about the dangers the quester faces in communing with nature in this way and asking for a vision.

The ‘Fall’ the inevitable depression becomes part of the return. For some this can be the sense of grounding back in the mundane urban world and all of its problems and human despair. As the beauty of the natural experience fades, the reality of what one left behind starts to fade. No one acknowledges or is bothered about the experience you have been through, your new life status goes unacknowledged in wider society.

Your gifts gained in the emotional, physical and spiritual struggle of the fast go unwanted and unnoticed.

My year of incorporation started well as I felt energised by the power of the fast but gradually went down hill. I started a relationship with a woman, who had a child, I thought this was a symbol of my ‘adultness’ the ability to act as lover and surrogate father. The woman I chose was either unable or unwilling to commit emotionally as I still was. What’s wrong with me? Why can’t I do this? The voice got louder and louder. My work started to really get me down. I was a manager at a drug rehab, the despair and slow para suicide of heroin and alcohol addiction in the clients I was working with started to mirror my own internal mental state. I think I had agreed intellectually with the Chiron myth of the wounded healer in my work, but now I started to feel wounded beyond repair, unable to help myself let alone others. What had happened? I felt cheated by the fast, it hadn’t delivered what it promised?

I slumped into a deep depression, suicide was a close friend, after the beauty of the natural world I had encountered in the fast and the warmth of my companions this felt like hell. The year of incorporation, as part of the overall process of the fast, was the most difficult part. In a way, being alone in the desert and not eating was easy; coming back and living the vision was very hard and almost killed me.

The descent into mental illness in the form a severe depression was not what I was seeking as a consciouness raising experience from my fast. This does not mean that such experiences cannot be very powerful in terms of their transformative potential for the psyche. My own experience was intrinsically linked with the voices and experiences of my own past and in the context of the work I had chosen, to help others in emotional distress. I think up until the experience of incorporation from the fast I had held onto the belief that ‘others’ experienced mental illness and that I was immune. I have felt for a long time that there is an element of the search for spiritual enlightenment that is about the seeker running away from reality into a fantasy escapism. There is a element of the fast and the ‘heroic journey’ that has this mythic and potentilly escapist quality, what I found was that the darker depressive and self destructive elements of my psyche where mobilised. By enaging in the fast the

‘heroism’ comes from the ability to sit with, bear and begin to understand these experiences. This process has been termed ‘the dark night of the soul’ The dark night of the soul is a concept that has been posited as part of a spiritual emergence process

(Grof and Grof 1991). It is the idea that, with exceptions, most people have to delve into a dark part of themselves and go to dark places in order to reach a state of freedom. Grof and Grof (ibid) discuss the most troubling and alarming components of the ‘spiritual emergency’; feelings of fear, a sense of loneliness, experience of insanity, and a preoccupation with death. For me this reads as a check list of emotions that I experienced during my year of incorporation, alongside feelings of utter despair and black numbness difficult to actually articulate in words. For Grof and Grof (ibid) these are often intrinsic, necessary and pivotal parts of the process of healing. For me, the notion of enlightenment through spiritual practice must be balanced with a notion

of darkness and that this too must be encountered in order to understand and fully integrate aspects of the self and into what may be a trasnformative process.

I believe the power of the fast process and the experience of isolation in a wilderness place mobilised some of my deeper unconscious fears and conflicts. I found I had to face to the psychodynamic elements of my personal emotional history that had caused me problems with intimacy. It is difficult to articulate how the experience mobilsed these feelings and by what mechanisms this may have happened on an intellectual level using words. It may be in the process of breaking down the idea of seprateness of self with the natural world that barriers within the self are broken down, the intersubjective nature of psyche, the self and the natural world constitutes a field of interconnection. In terms of psychology and particular ego psychology, there is a sense of self that is clearly separate from that which surrounds it. The nature of mind and emotions must first be encountered and understood before we can move beyond ego. From an Eastern point of view this could be seen as nonduality, the defenses of my ego were broken down by the experience, I was unable to fully experience egolessness without encountering the residue of negative feelings that had been stored somewhere in my psyche.

Desikachar (1995) in discussing the concept from a yogic point of view proposes that in order to know non-dualism ‘Advaita’ one must know dualism. In this sense the ego must believe it is separate from nature, certainly a notion that has grown with our ego bound technological society. To participate in the questing process and to fast is literally to empty out to fill oneself up with this connection, to feel at one with nature.

It is this aspect of connection that sits in opposition to non dualism and allows a moving beyond the separate ego bound state so common to eastern traditions such as

Yoga. Non-dualism for anyone who practises meditation regularly is not something that can be arrived at easily (if at all). I have in my meditations within natural environments felt a profound sense of connection and joy to things greater than and beyond my ego bound self this feeling is of course fleeting and cannot be ‘kept’. I think the process opened up aspects of my ego that were very problematic and needed to be encountered in order for me to grow. In his discussion of the transpersonal nature of ecopsychology, Davis (1998) proposes the concept of non-duality is linked to nature and can be seen as part of a transpersonal process. When I was present in nature particularly during the threshold phase, I expereinced a sense of one-ness with nature, a feeling of being at one with and a closeness and affinity to the plants, animals, rocks and earth; a sense that there are no boundaries. Indeed it this disconnection from the natural world that had already been posited as contributing to our present psychological problems, and certainly environmental problems.

In terms of making sense of the transformational process that I experienced during and predominantly after the fast, I sruggled to understand what had I had been through and how to make sense of it. To encapsulate the meaning in the form of a narrative has been an emergent process for me, a way of storying and giving the experience a meaning. The ‘hero myth’ can itself be problematic,do we discover ourselves within myth or make for ourself a personal myth? (McAdams 1993) There is the possibility of meaninglessness lurking behind the personal myth making structure or the form of the heroic journey. For Satre and the existentialists we must consider the possibility that nothing has any meaning, we must reject ‘bad faith’ and

the notion that religion or spirituality can create a structure for meaning,. It is in toying with the possibility of meaninglessness that a more authentic meaning can be created from experience. The ability to create and sustain a personal story in the form of a myth is what makes us essentially human and therein lies the transfromative potential of any journey and experience. The elements of the fast and the return from it are for me too intensely personal and seemingly interlinked for the process to be devoid of any meaning. The relationship between the unconscious, through which archetypes are felt and the outer workings of nature are connected to in whatever form, has significant potential for mediating meaning and healing within our psyche(P.101 Yunt 2001). No more so was this felt when synchronistic events occurred during my preparation and incorporation phase. These events were an important part in helping my understanding and giving overall meaning and structure to my journey. An example was when I was thinking about getting a dog and the commitment this involved. Whilst out walking in nature contemplating this dilemma I found a dog lead sitting next to me on a tree trunk, it seemed a powerful message to get a dog. This seemed to be a clear example of synchronicity, in that it was a simultaneous occurrence of a certain psychic state with one or more external events which in turn, paralleled my subjective state (Main 2000).

To conclude I want to draw on both Ferrer’s arguments that participatory knowledge is at the root of transpersonal understanding and is a co-creative spiritual process and the Ecofeminist argument that subjectivity, feeling, emotion and caring are legitimate sources of knowledge (Booth 2002). It is in the experience of the sacred and the profane, the mundane and the subtle, both seen as flip sides of the same coin that aspects of transpersonal knowing come to the fore. They offer us a future where the misconception of our duality with nature and therefore ourselves and our psyche is exposed as the fallacy that it is.

References:

Black Elk (1972) Black Elk Speaks: being the life story of a holy man of the Oglala

Sioux/ as told through John G. Neihardt (Flaming Rainbow) London: Barrie Jenkins

Booth, A, (2002) ‘Ways of Knowing: Acceptable Understandings Within

Bioregionalism, Deep Ecology, Ecofeminism and Native Amercian Cultures’ The

Trumpeter http://trumpeter.athabascau.ca/content/v16.1/booth.html

(Accessed

September 26th 2005)

Burns, G. (1998) Nature Guided Therapy: Brief integrative strategies for health and well-being London: Taylor Francis

Campbell, J. (1949) The Hero With A Thousand Faces Princetown: University Press

Chodron, P. (2001) The wisdom of no escape: how to love yourself and your world

London: Element

Davies, J. (1998) ‘The Transpersonal Dimensions of Ecopsychology: Nature, Non

Duality and Spirit’ The Humanistic Psychologist, 26 (1-3), 60-100

Davies, J. (2003) ‘’An Overview of Transpersonal Psychology’

The Humanistic

Psychologist 31 (2-3), 6-21

Desikachar, T.K.V. (1995) The Heart of Yoga Vermont: Inner Traditions India

Dow, J. (1986) ‘Universal aspects of symbolic healing: a theoretical synthesis’

American Anthropologist 88 , 56-59

Ferrer, J.N.(2002) Revisioning Transpersonal theory: A Participatory Vision of

Human Spirituality New York: Suny

Ferre, J. N. (2005) Spiritual Knowing: A Participatory Understanding in Clarke, C.

(Ed) Ways of Knowing: Science and Mysticism Today Exeter: Imprint Academic

Foster, S. and Little, M. (1998) The Four Shields: The Initiatory Seasons of Human

Nature Big Pine CA: Lost Borders

Foster, S. and Little, M. (1983) The Trail to the Sacred Mountain: A Vision fast

Handbook for Adults Big Pine CA: Lost Borders Press

Foster, S. and Little, M. (1989) The Roaring of The Sacred River: The Wilderness

Quest for Vision and Self Healing Big Pine CA: Lost Borders Press

Foster, S. and Little, M. (1992) The Book of The Vision Quest: Personal

Transformation in The Wilderness New York: Fireside Books

Grof, S. and Grof (1991) The Stormy Search for Self: Understanding and Living With

Spiritual Emergency London: Harper Collins

James, O. (2005) ‘Life on the Couch: The mental Block’

The Observer Magazine 14 th

August 2005

Lukoff, D. (1985) The reinterpretation of mystical experiences with psychotic features’ Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 17 (2), 155-181

Main, R. (2000) ‘Religion Science, and Synchronicity’

Harvest: Journal for Jungian

Studies 46 (2), 89-107

McAdams, D. (1993) ‘The stories we live by: personal myths and the making of the self’ NewYork: Guildford

Rozack, T (1992) The voice of the earth New York: Simon & Schuster

Segal, F. (2005) ‘Ecopsychology and the uses of wilderness’

Ecopsychology on Line http://ecp[sychology.athabascau.ca/1097/segal.htm

(Accessed on August 17, 2005)

Van Gennep, A. (1960) The Rites of Passage Chicago: University Press

Walsh, R. (2001) ‘Shamanic experiences: A developmental analysis’ Journal of

Humanistic Psychology 41 (3), 31-52

Yunt, J. (2001) ‘Jung’s Contribution to An Ecological Psychology’ Journal of

Humanistic Psychology 41 (2), 96-121

Zweig, C. and Abrams, J. (Eds) (1991) Meeting The Shadow: The Hidden Power of the Dark Side of Human Nature London: Penguin